Michael J. Altman received his Ph.D. in American Religious Cultures from Emory University and is an Instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama. Mike’s areas of interest are American religious history, theory and method in the study of religion, the history of comparative religion, and Asian religions in American culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript analyzing representations of Hinduism in nineteenth century America. This post originally appeared at Mike’s personal blog. He graciously allowed the Juvenile Instructor to repost it in its entirety.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

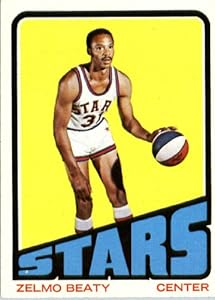

Every week host Josh Levin signs off with the phrase “remember Zelmo Beaty.” Beaty, a basketball star in the 60s and 70s passed away recently and this past week Hang Up and Listen reminded us why we should indeed remember him. Stefan Fatsis’ obituary of Beaty opened by staking out Beaty’s importance as a pioneer for black players in professional basketball. But what caught this religious historian’s attention was the confluence of race and religion that surrounded Beaty’s move to Salt Lake City to play for the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association in 1970.

Free agency in sports was still years away, so Zelmo had to sit out a season in order to be released from his NBA contract. But during that season, the Stars were sold to Bill Daniels, a pioneer in cable television. Daniels moved the team to Salt Lake City, the population of which was literally 99 percent white. Beaty announced that he wouldn’t report if the team went to Salt Lake, in part because of tensions between black athletes and the Mormon Church, which didn’t let blacks serve as priests. Sports Illustratedreported at the time that that local leaders assured Daniels that his players “would be well treated.” Beaty and his wife Ann made their own visit, were satisfied with their housing options, and agreed to go. All of the other black players on the Stars followed.

Beaty then led the team to the 1970-71 ABA title and won the MVP for the playoffs. But even more than that Beaty changed the face of basketball in Utah.

The Stars eventually started an all-black lineup in all-white Salt Lake City. Beaty wound up playing four seasons there, and he deserves clear credit for making the city a viable place for pro basketball. As SI wrote in 1974, “Beaty quickly gained acceptance from the Utah fans, not only by leading the Stars to a championship in their first season, but by remaining quietly congenial and displaying his considerable innate dignity. He remains the only black player who owns a house in Salt Lake. And, according to other players, Beaty passed the word around the ABA that Utah was an all-right place to play.” The Stars would fold when the ABA and NBA merged in 1976, but the city regained a franchise when the Jazz moved from New Orleans in 1979.

We would never have gotten Stockton to Malone without Zelmo Beaty.

So, for historians interested in questions of race, religion, and sports: Remember Zelmo Beaty.

Your penultimate line belongs in The New Yorker‘s “Words of One Syllable” department. You meant that we’d have never got to Stockton to Malone without the Big Z.

But, thanks for this. I didn’t know any of this story behind the story. All I remember is Bill Sharman coaching the Stars that first year in Salt Lake City, and old nearly forgotten names like Zelmo Beaty, Willie Wise, Wayne Hightower and Ron Boone, and even Dick Nemelka and Jeff Congdon from BYU.

Comment by Mark B. — September 13, 2013 @ 7:08 am

Thanks, Mike. I’m reminded of Matt Bowman’s thoughts on these themes as they apply to the Utah Jazz, and as you hint, the experience of Zelmo Beaty and the ABA’s Stars seems like crucial context for the Jazz’s subsequent inception, development, and reception in Utah.

It seems like a more formal and expanded essay on basketball, race, and religion in Salt Lake City is begging to be written.

Comment by Christopher — September 13, 2013 @ 7:19 am

Thanks for this, Mike. Really enjoyed it.

Comment by J Stuart — September 13, 2013 @ 11:28 am

It’s too bad no one ever did an oral history with Beaty. I’m sure he had some interestingly uncomfortable stories about well-meaning Mormons.

Comment by Joel — September 13, 2013 @ 11:52 am

Wow, I’m like Mark, remembering all those names from the Stars. It played out a little differently in Ogden, which as a railroad town and the closest city to Hill AFB, had a much higher percentage of blacks than Salt Lake City. Our Weber College Wildcat team had black players I believe before even the University of Utah, including Willie Sojourner, who went to the ABA in 1971, I believe. When examining race relations in Utah, Ogden becomes kind of a special case. At this time, I believe Ogden not only had the highest percentage of black residents, I believe they had more black residents than the entire rest of the state. While it led to more exposure and acceptance of blacks at schools and in the city, as the largest minority at the time, there was also more significant discrimination in housing in Ogden. The Hi Fi Shop murders in 1974 exposed some ugly undercurrents in race relations in Ogden that many people assumed didn’t exist.

Comment by kevinf — September 13, 2013 @ 3:08 pm