By Mark Ashurst-McGee

As explained in the previous installment (2 of 4), I had found what I believed to be the source of the content of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Kinderhook plates: The Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language (GAEL).

A few months after this discovery, I got a call from my friend Don Bradley who told me that he had independently found the same source—the definition in the GAEL that matched what Joseph Smith had said about the Kinderhook plates. But Don had figured out much more than I had. He had also figured out just how Smith had come up with that particular definition as translation material for the Kinderhook plates.

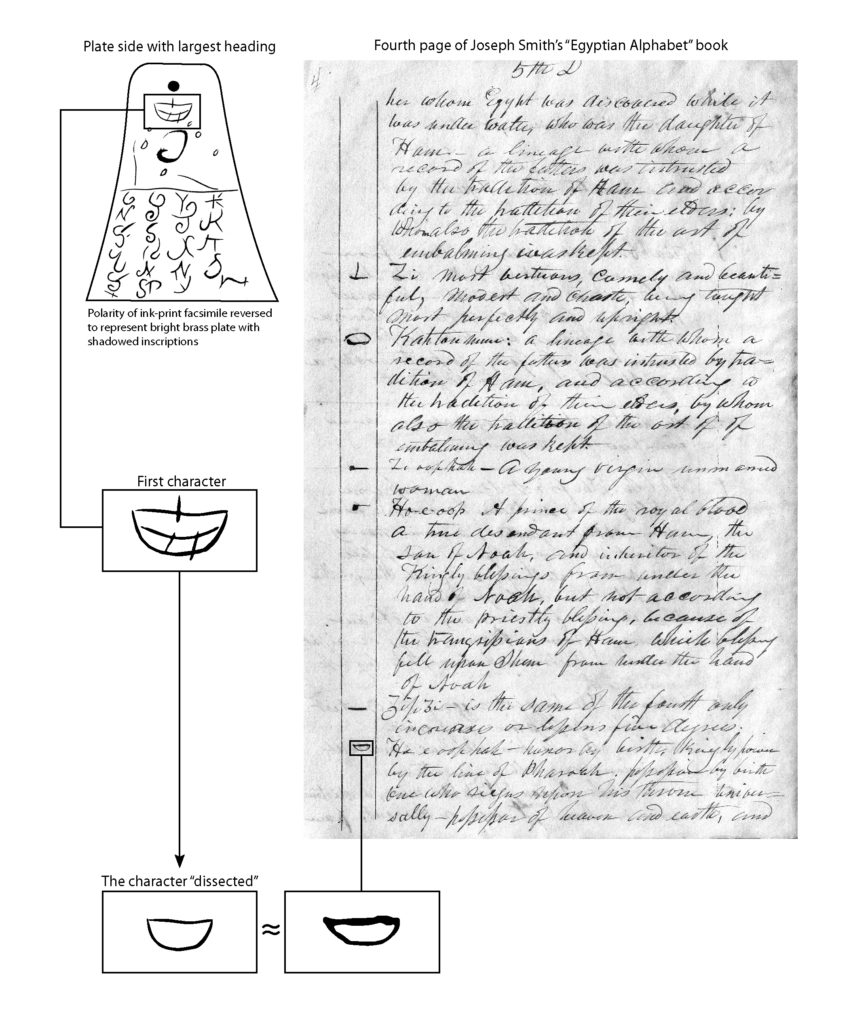

Don had taken a good look at the Egyptian character in the GAEL that was associated with the relevant definition, and then he had scanned the Kinderhook plates for a similar character, and he found just such a character at the top of one of the Kinderhook plates.

This similarity of characters apparently affirmed that Smith did translate from the plates and indicated that he had done so through character matching followed by the adaptation of a corresponding lexical definition into a translation. In other words, his translation attempt had been by a conventional translation method (see diagram).

The information Joseph Smith had conveyed to William Clayton—about the plates being a history of a descendant of Pharaoh—was apparently derived from this single character at the top of one of the plates.

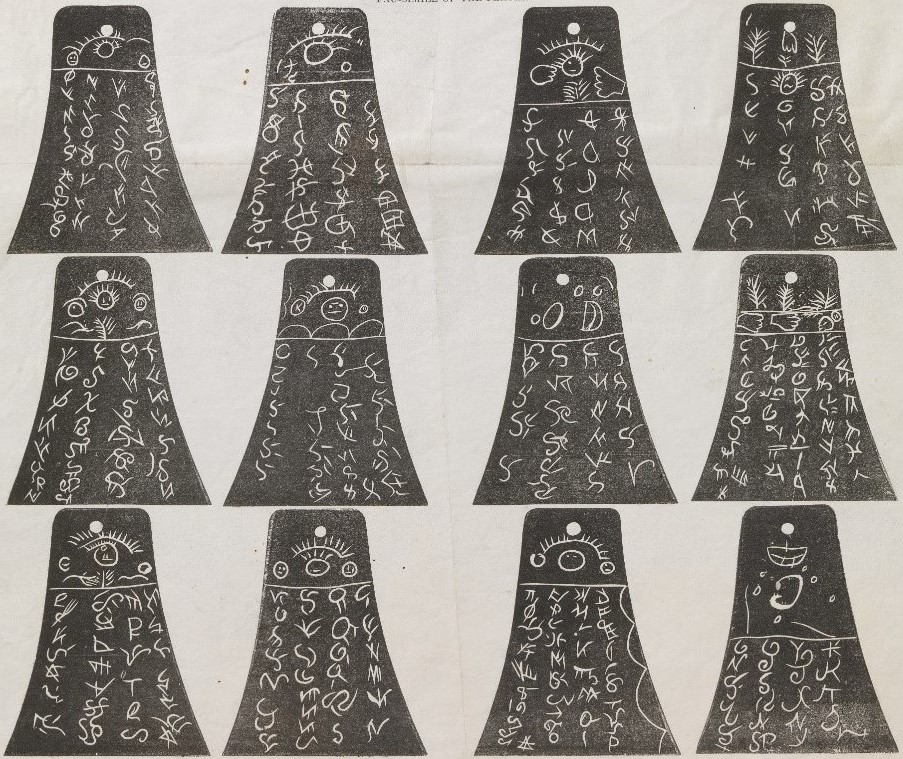

I examined this character within its inscription context—on the side of the plate where it appeared—and then compared that with the inscription patterns on the other eleven sides of the six plates (relying upon the print facsimiles published in Nauvoo). Each side of each plate is divided into top and bottom sections by a horizontal line. On all but one or two of the twelve plate sides, it is fairly clear that the areas above the line are inscribed with illustrative figures, while the areas below the line are filled with columns of characters. I noticed that the character Don had identified at the top of one of the plate sides was in the heading, or top section, of the plate side that had a disproportionately large heading (in comparison to the size of the headings on the other plate sides). Moreover, I noticed that it was on the only one (or possibly two) plate sides where the area above the line featured characters instead of illustrative figures. Furthermore, I noticed that the two characters in this heading were significantly larger than the other characters on the plates (found in the bottom sections). In other words, it may not have been a random 1-in-12 chance that Joseph Smith attempted to begin translating from the Kinderhook plates with the first character on this side of this plate. For an enthusiastic would-be translator, looking for a place to begin translating, there may have been reason to begin with this precise character to which Don was pointing (see the final plate side in the broadside array of print facsimiles).

At this point, Don and I decided to join forces and write an article on Joseph Smith’s translation of the Kinderhook plates.

We did research now and then, and we occasionally kept in touch, but we also kept letting other projects get ahead of our work on the Kinderhook plates.

Then, about a decade later, Don made another very important find—a 7 May 1843 letter from someone living in Nauvoo to whom Smith had shown the Kinderhook plates. This anonymous correspondent reported that he had personally witnessed Smith comparing characters on the plates with characters in his “Egyptian alphabet.” This was on the same day that, according to Smith’s journal, he was visited at his home by several “gentlemen” regarding the Kinderhook plates and the Hebrew lexicon in Smith’s office was sent for. This newly discovered letter was a strong confirmation of our secular translation thesis. Don was also able to determine that Sylvester Emmons was the anonymous author of the letter (Emmons was a non-Mormon attorney living in Nauvoo).

About a decade after that, Don and I finally finished up enough research and writing to submit a version of our study for publication. Our findings obviously lent themselves to LDS apologetics, and so we wrote an apologetic version of our findings for the anthology edited by Laura Harris Hales, A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine & Church History (Religious Studies Center, BYU, 2016).

And now, finally, after almost three decades of on-and-off research, we have published a scholarly version of our findings as a chapter in the newly released Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity (UoU Press).

I’ll tell you a little bit about this scholarly version of our findings in the next (and final) installment.

Really interesting background. Thanks, Mark.

Comment by Gary Bergera — August 27, 2020 @ 8:30 am

Presumably, the guys who forged the Kinderhook plates did not have access to the GAEL. Is it pure coincidence that a prominent character on the plates happened to correspond to a character in the GAEL? Are there other characters on the plates that match those in the GAEL? Did Joseph perhaps abandon the effort when he couldn’t identify enough (any?) additional characters on plates? Or was he just too busy to pursue it further?

Comment by Last Lemming — August 27, 2020 @ 9:00 am

Last Lemming, excellent questions!

No, the guys in Kinderhook (about 70 miles downriver from Nauvoo), who forged the Kinderhook plates, did not have access to the GAEL, which was at Joseph Smith’s house in Nauvoo.

Yes, there may be other characters on the Kinderhook plates that resemble characters in the GAEL. According to Sylvester Emmons, there was a favorable comparison of “characters” (plural), so it seems that more than one match was identified. I think your scenario of Joseph abandoning the effort when he couldn’t identify enough matches is entirely plausible. Or, alternatively, he perceived enough matches to make an attempt but was not able to string the GAEL definitions associated with the character matches into a sensible translation. This is all about 1843 May 1-7. The June broadside of print facsimiles stated that the translation of the plates will be published as soon as it is completed. Presumably this was motivated in part by the financial aim of increasing subscriptions to the church newspaper (as with the promises of further installments from the Book of Abraham), but must have also been based on some actual expectation. However, Smith was murdered before ever returning to either the Book of Abraham or the Kinderhook plates.

Comment by Mark Ashurst-McGee — August 27, 2020 @ 10:04 am