My thanks to series editors J Stuart and Cristina for their edits and comments on this post.

I haven’t read Under the Banner of Heaven; this post is about responses to the book that I have heard. After reading the book, my sister shared with the family her take on the book’s claim of the dangers of believing in personal revelation (Jana Riess makes the same observation about Krakauer’s claim in her review), and it was at that point that I began formulating what I’d observed from studying the history of Christianity: there’s been a long history of people being very worried about other people claiming revelations. No doubt such claims got Jesus in trouble as they did Socrates. After studying this topic in considerable depth, I’d say the worry of the potential threat of visionaries vastly outstrips the actual damage of such people, and thus it looks to me like Under the Banner of Heaven is a popular manifestation of an ancient claim.

Christians wanted to limit claims to personal revelations ever since the second-century Montanists and the move toward a closed canon was part of such limitations. Revelations were seen as possible but dangerous by authorities during the Middle Ages, while the Reformers wanted to ground the ultimate authority in the Bible (as they interpreted it) and thus rejected the posibility of visionaries. Yet, the disorder of the Reformation era actually led to a rise of prophets, much to Martin Luther’s chagrin. Luther labeled such people as schwarmer (he meant it as an insult) and such visionaries took on very political implications in two very important instances: the Peasants Revolt of 1525 and the takeover of the German city of Münster by radical visionary Anabaptists in 1534 (more on the Münster below).

While not instigated by visionaries, the visionary Thomas Müntzer quickly got involved with the peasants’ revolt and thus was used for the narrative visionaries caused disorder. No doubt 16th-century oligarchs hated the idea of revolution, and Luther demanded that the peasants “be sliced, choked, stabbed, secretly and publicly, by those who can, like one must kill a rabid dog.” But the peasants’ call for an end to serfdom and to lower church taxes seems to pretty obviously put Müntzer in a more moral position than Luther.

As I have written previously, Elizabeth Barton posed one of the most significant political challenges to Henry VIII’s divorce and reforms, so Henry’s henchmen extracted a false confession, including lots of illicit sex, and had her head chopped off and placed on London bridge without a trial. Visionaries were not going to stand in the way of state power, and Parliament outlawed false prophecy in 1541, which, according to mainline Protestantism, included all prophets.[1]

Yet claims to visions continued and really took off during the English Civil War and interregnum (1640-1660) when Parliament overthrew the king, chopped off his head, and placed Oliver Cromwell in charge as the protector. Not only did the war and interregnum lead to societal disorder and the hopes for a world turned upside down, but Cromwell himself went to great lengths to expand the franchise, religious freedom, and remove censorship laws. Visionaries were now freer to do their thing, and one of the great visionary religions emerged soon after, including the Quakers with their belief in the primacy of the inner light; Cromwell even made it a point to invite visionaries to come and make their case to Parliament.

Such openness to visionary political advice no doubt sounds kind of crazy from the modern point of view (and really bothered a lot of people at the time) but the results of such actions is best demonstrated in the case of the visionary Elizabeth Poole. As Parliament debated whether or not to execute Charles I, they brought in Poole who declared that God said they should not execute the king but should expand the vote. But in response, a council member questioned her on English law, befuddling her and mockingly dismissing her.[2] Cromwell and his people then went ahead and executed Charles I. The visionaries weren’t running things.

And yet, all of Cromwell’s religious freedom terrified the oligarchs as Quakers and Firth Monarchists seemed to run amok. After Cromwell’s death, Fairfax quickly worked to reinstate Charles’s son, Charles II, out of fear of what the free-range visionaries would do to society.

But what did the Quakers do to society? The Quakers have just about the best track record of any religion as they played significant roles in the advance of religious liberty, anti-slavery, women’s rights, and a host of social reforms in their push for general egalitarianism. Quakers were quite radical in their early years but played a major role in advocating for religious freedom in colonial New England, especially when Quakers William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, and Mary Dyer kept returning to Massachusetts despite being banished. When asked why she returned despite the threat of execution, Dyer declared, “I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them.” The Quakers’ executions resulted in the crown eliminating such actions in Massachusetts, and the Quaker persecution served as an icon of the need for religious liberty in the United States.

[Mary Dyer on the way to her execution. An unknown 19th-century artist]

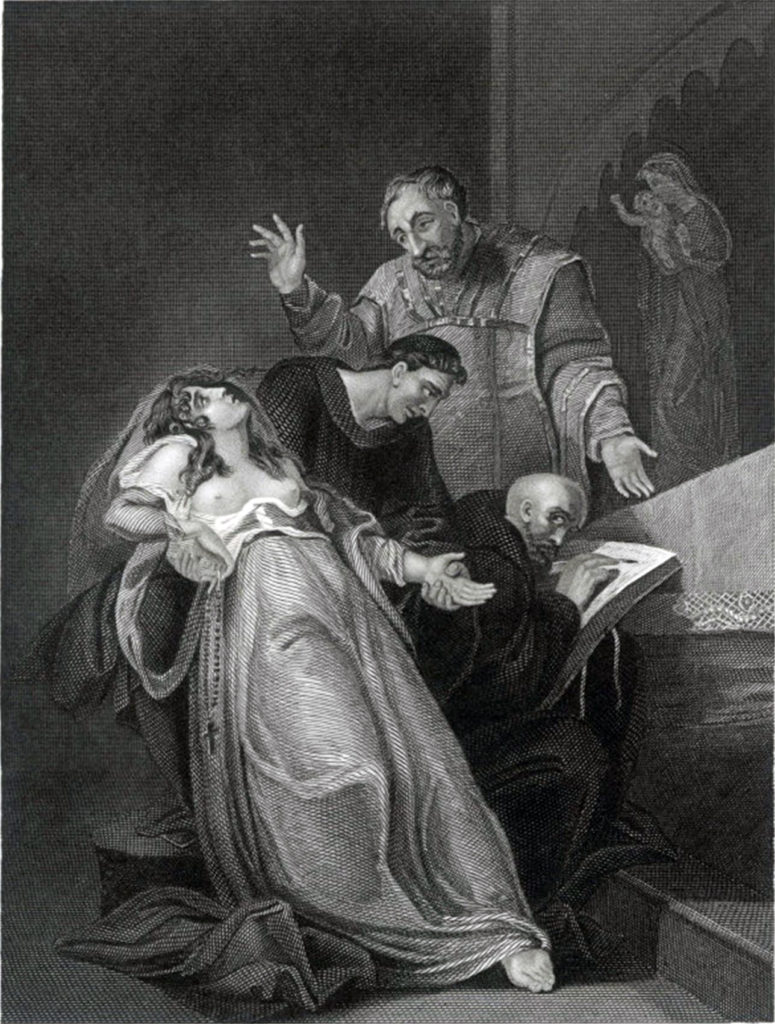

And yet the fear of visionaries continued as 18th-century enlightenment thinkers continued to push the trope of the dangers of visionaries to the body politic. David Hume mocked Elizabeth Barton as the ultimate example of past foolishness from which the English people had advanced. [See the picture below]. But what would have happened if the authorities listened to the visionaries that I cited above: greater rights for the peasants (Müntzer) which were eventually granted, religious liberty (Quakers) granted, not killing the king, and expanding the vote (Poole), which are both widely held ideas. Henry listening to Barton would have ended his divorce and reformation plans, and, no doubt, the notion of the wonderful progress caused by the Reformation is a major trope of popular whiggish notions of Anglo-American history. But further study certainly demonstrates that notions of holy Protestantism over evil Catholicism are greatly overblown. Undoubtedly, the visionaries placed themselves in controversial situations, but most of their agendas don’t look very radical from today’s perspective.

[An engraving depicting Elizabeth Barton printed in David Hume’s History of England meant to present foolish pre-modern Catholics listening to a crazy (somehow topless) girl]

And now for the second and perhaps the greatest historical example of those deemed the greatest political crazies: the Münster Anabaptists. Such started as followers of the visionary Melchior Hoffman before Jan Matthys declared the New Jerusalem would be in Münster rather than Strassburg. There they voted in Anabaptist magistrates and dispensed with the Lutheran ones under the agenda of “the absolute equality of man in all matters, including the distribution of wealth” and declared Münster to be Zion. The expelled bishop then led an army to besiege the city, which fell a year later, and the leaders were tortured to death. Münster was held up as the ultimate in the dangers of religious fanaticism, and such clams were still very alive in the early nineteenth century leading to frequent comparisons to Mormons, especially since the Münsterites practiced polygamy.[3] These Anabaptists infuriated the authorities so much that replicas of the gibbets that held the tortured bodies of the leaders still hang from the local cathedral to this day.

[Replica gibbets of the ones that held Münster Anabaptist leaders hanging from the steeple of St. Lambert’s Church in Münster]

Yet, I’ll ask the same question of the other visionaries: what if the Münsterites were left alone and granted a degree of toleration? No one conceived of religious freedom at that time; that took the sacrifice of groups like the Quakers and a few hundred more years. Here the long-made connections to Mormonism are helpful. Social commentators long claimed that the Münsterites were proof of the dangers of visionary religious radicals and the need to curb religious freedom, but I do think that Mormon history helps answer the question of whether allowing Münsterite behavior—revelations, polygamy, and holy cities—would lead to the downfall of the body politic? I think it’s pretty clear that it did not.

So now to the question of are visionaries good or bad for society and human history? No doubt I’m biased, but I’ve also studied the question, and I’d say that it’s been an overwhelming good (Socrates, Jesus, St. Francis, Hildegard and Bingen, Elizabeth Poole, the Quakers, etc.) with some pitfalls along the way. Overall, such visionaries hoped for a better world, to make earth more like heaven, and many of the visionaries listed above played significant roles in improving society.

I would also note that some of the most horrific cases (the Lafferty brothers and Vallow/Daybell) illustrate a point that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders makes about delusion (a point Ann Taves in her study of JS’s visions)[4]: “a person cannot be diagnosed as being delusional if the belief in question is one ‘ordinarily accepted by other members of the person’s culture or subculture.’” Visions aren’t delusions if believed by a group. Delusion is either individual or takes place within a very small group, what psychologists call Folie à deux, or folly of two or when a delusional person talks another person into that delusion.

The Lafferty and Daybell cases seem to indicate that dynamic as both Ron Lafferty and Chad Daybell were not able to get their associates to follow them when their claims became increasingly extreme and murderous. Both only had one follower (maybe two with Daybell, there is also Folie à Trois) follow them all the way, which would thus (it seems in my lay observance) put them in the category of Folie à deux. Youtube psychologist Dr. Grande recently discussed the Lafferty brothers and argued for the brothers having “shared psychotic disorder,” another name for Folie à Deux, and noted the similarities to Daybell and Vallow.[5] Murder through delusion wouldn’t be stopped by eliminating claims of talking to God: Son of Sam killed six people at the command of his neighbor’s dog. Perhaps Mormons are particularly vulnerable to Folie à Deux (a topic that seems worth studying since Elizabeth Smart’s captors seem to fit the profile), but I think it is essential to be aware of these dynamics when making claims about supposed negative societal effects of revelation.

[1] Tim Thornton, Prophecy, Politics and the People in Early Modern England (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2006), 26.

[2] Manfred Brod, “A Radical Network in the English Revolution: John Pordage and His Circle, 1646-54” The English Historical Review 119, no. 484 (2004), 1234, 1237-38. Poole was a liaison between the “levelers” in the army who wanted universal manhood suffrage, and parliament, who, though they expanded suffrage in the interregnum, didn’t want to go as far as the levelers.

[3] J. Spencer Fluhman, “A Peculiar People”: Anti-Mormonism and the Making of Religion in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 84-85; D. Michael Quinn, “Socio-religious radicalism of the Mormon church: a parallel to the Anabaptists,” in New Views of Mormon History: A Collection of Essays in Honor of Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987). After Jan Matthys was killed in a sortie against the siege, Jan van Leiden took over and was said to have become more radical. Scholars debate whether all the charges against van Leiden were true or not including abundant executions. Either way, the Münster Anabaptists ended up with a very bad reputation that was applied to visionaries and religious radicals for centuries.

[4] Referring to Taves’s reference to delusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is not an attempt on my part to diagnose Lafferty, Vallow, Daybell, or Mitchell, but instead to argue that I find Taves’s application on the separation between delusion and religion as a social construct useful. Studying visionary religious origins is pretty tricky from a scholarly perspective and thus taking the angle of the importance of social construct can be helpful in these cases. If Joseph Smith couldn’t convince anyone of his visions outside of his family he would not have founded a religion and no one would consider him a prophet. Thus the reverse as a social construct seems useful in the cases I’ve mentioned: if a visionary’s demands grow so radical as to alienate all of his or her associates but one, from a social point of view, it would seem that person lost visionary status. This is not to argue against the reality of mental illness, nor, again, is it an attempt at diagnosis, but just to note that the mentally ill tend to struggle to get adherents.

[5] Grande, even though he says at the beginning of every video, “a reminder, I’m not diagnosing anyone in the video, only speculating about what might be happening in a case like this,” argued that the court clearly was wrong to claim that the Lafferty brothers weren’t psychotic. But Grande agreed that regardless of the diagnosis, the Lafferty brothers were dangerous and needed to be locked up.

To answer the question, it seems like someone would need to look at how many visionaries aren’t associated with violence, and the answer would probably be: many, many times more than those that are. Or in other words, visionary experiences are no more related to violence and upheaval than they are to nearly anything else.

Also, Hoffman himself wasn’t a visionary, although he was associated with a number of visionaries in Strassburg.

Comment by D. Martin — May 6, 2022 @ 9:28 am

I’ve always heard Hoffman described as a visionary, but I just took a look at his Wikipedia page and saw it was more in line with exegesis, perhaps like Joachim of Fiore and William Miller. Still, it seems that people like that with very specific predictions could be described as visionary (as the Wikipedia page describes Hoffman.)

Yes, I think it’s quite clear that only a tiny percentage of those claiming divine inspiration advocate violence and most of the violent ones would fall under folie a deux. At that same time, I do have sympathy for those who advocated upheaval in hopes to throw off oppression like Thomas Muntzer and Nat Turner. Such people may be legitimately seen as a danger to the establishment, but such establishments were oppressive and needed to be reformed or even overthrown.

Comment by Steve Fleming — May 6, 2022 @ 11:56 am

None of Hoffman’s works contains a vision he saw or otherwise received. He did describe himself as an inspired interpreter of scripture (see Deppermann 1987, 62-66), although that’s a category that would contain many more people than visionaries. Especially if you broaden it to people making specific predictions, the category would be gigantic.

Comment by D. Martin — May 6, 2022 @ 3:10 pm

Thanks for the insights. But those who make specific predictions about the future that have important effects are often placed in the revelatory category like Joachim.

Comment by Steve Fleming — May 6, 2022 @ 3:30 pm

A minor tour-de-force. Thanks Steve.

Comment by Mark Ashurst-McGee — May 11, 2022 @ 10:37 am

Thanks, Mark. I do hope people will be a little more cautious on the claims they make about this topic.

Comment by Steve Fleming — May 11, 2022 @ 6:14 pm