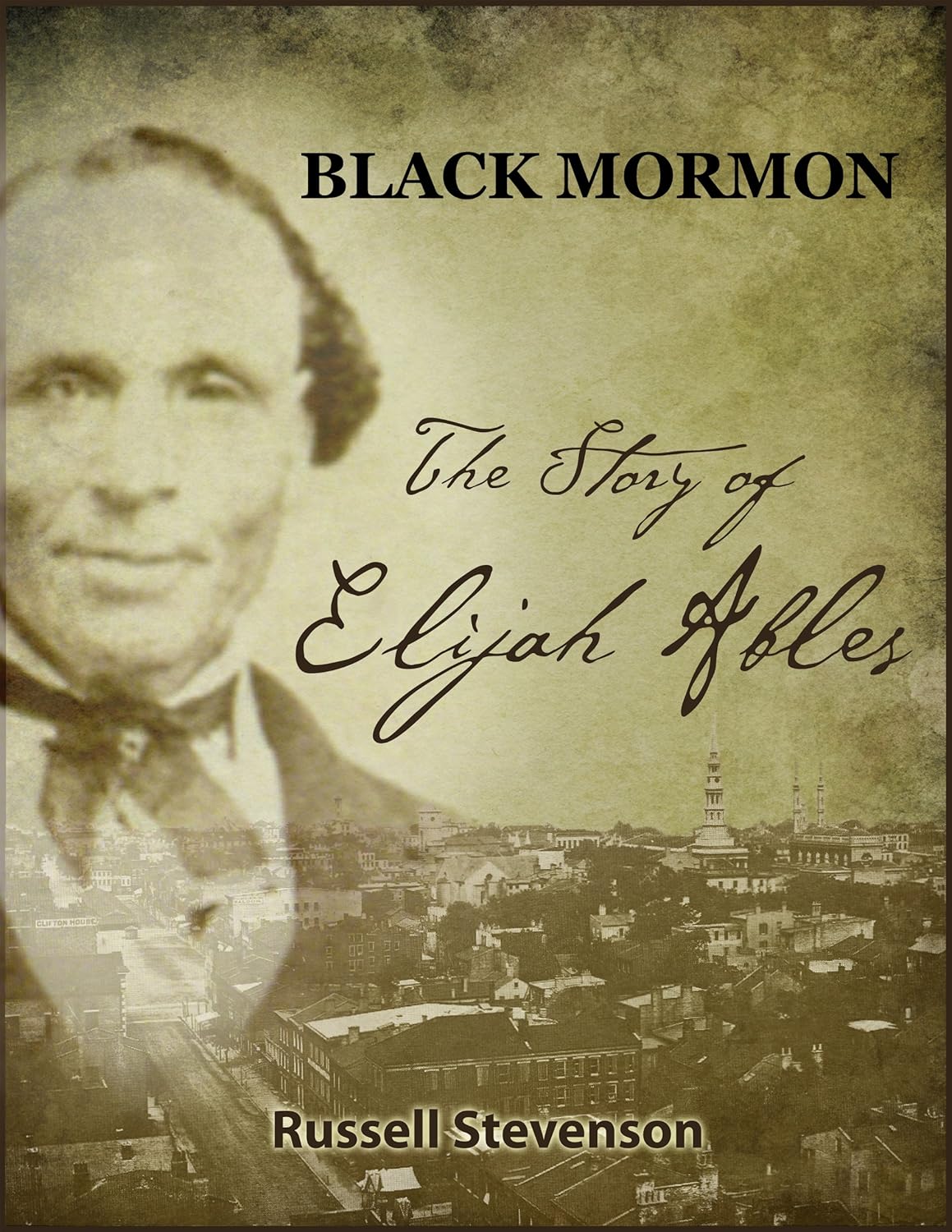

Recently, two biographies were published on Elijah Abel/Ables, a black Mormon man who held the priesthood in the nineteenth century with the blessing of Joseph Smith and many of his contemporaries. Rather than attempt a traditional review, I decided to write a conversations post with Russell Stevenson, the author of one of the two biographies. Stevenson is an independent scholar with a master?s degree in history from the University of Kentucky. He recently self-published Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables.

Recently, two biographies were published on Elijah Abel/Ables, a black Mormon man who held the priesthood in the nineteenth century with the blessing of Joseph Smith and many of his contemporaries. Rather than attempt a traditional review, I decided to write a conversations post with Russell Stevenson, the author of one of the two biographies. Stevenson is an independent scholar with a master?s degree in history from the University of Kentucky. He recently self-published Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables.

In order to make the post easier to read, I have arranged the questions I asked and Stevenson?s responses into categories.

General Questions

The Spelling of Abel?s Name

Amanda: In your book, you use a spelling of Elijah Abel’s name that many readers will be unfamiliar with. Where does it come from? Why did you decide to go with that spelling?

Stevenson: In my book, I give a brief synopsis of the possible candidates for the spelling of the name, as well as a discussion of the rationale for using the Ables rendering. For example, the 1850 and 1860 census enumerators spelled his name as “Elija/Elijah Able.” In 1870, it became “Elijah Ables.” Newspaper reports offer an even wider array of options, including Abel and Abels. My work did indeed unearth two documents presenting renderings of Ables’ name: “Elijah Ables” and “Elijah Able.” The first rendering comes from a letter written/dictated by Ables to Brigham Young in 1854; this is the earliest known documentation of Ables’ name in manuscript form. The second signature comes from a receipt of payment in 1858 for work Elijah performed for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund.

A: One of the things that struck me about the difference between the two signatures is that the first seems to come from a more practiced hand whereas the second seems to be the signature of someone who has less practice with writing. The second approaches letters differently (note the additional loops), has a faint wobble to it, and has additional letters (there’s an extra e, i, and j between some of the letters). What evidence do we have that convinces that the letter was from Abel’s own hand rather than dictated to someone else and then sent as was common practice in the 19th century? Also, what difference, if any, do you see this change in name making historiographically?

S: I also noticed these differences in the rendering. According to one observer recalling Ables in 1838, he struggled with literacy, so it is entirely possible that he dictated the letter. My general rule of thumb is to place more credence on the earlier documentation; therefore, I have chosen to use the “Ables” spelling since it represents the first signature directly traceable to Ables’ person. Whether or not he wrote out his name with the additional “s,” the spelling does suggest that he pronounced it that way when speaking. Readers could, of course, make a defensible case for using the “Able” spelling as well.

The historiographical issues mostly conform to what we already know about the fluidity of nineteenth-century spelling patterns. Even literate individuals spelled their name differently over time. Mary Owens, a romantic interest of Abraham Lincoln’s, had a sister who spelled her name, Elizabeth Abell. Yet Johnson G. Greene spelled her name as “Able.” Parthena Hill referred to Elizabeth’s family as “the Ables family.” As Stephen Wilson has argued, “uniform spelling did not really become de rigeur among the upper and middle-classes in England until 1830.” The lower classes trailed behind.

See Elizabeth Abell to William Herndon, January 13, 1867, http://durer.press.illinois.edu/wilson/html/544.html; Greene statemeent, 1866, http://durer.press.illinois.edu/wilson/html/530.html; Stephen Wilson, The Means of Naming: A Social History (London: Psychology Press, 2004), 250 and Richard Venezky, The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English(New York: Guilford Press, 1999), 217. See also Walter B. Stevens, A Reporter’s Lincoln (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1916), 9.

Historical Interventions

A: In the promotional materials that you created on Facebook for the biography, you mention that you are using several previously untapped documents and that this biography moves beyond our understanding of Abel’s life. As someone who was relatively unfamiliar with Elijah Abel’s life, I had trouble identifying these documents and the interventions that you were making in the book. What new documents did you find? How do they change the stories that we usually tell about Abel’s life?

S: Newell Bringhurst and Lester Bush deserve much credit for resurrecting the memory of Elijah Prior to their research, Elijah Ables had been reduced to being the “token black man” in Mormon history–an historical outlier hardly worthy of note. Bringhurst was the first scholar to give us a sense for the course of Elijah Ables’ life.

The unpublished documentation allowed me not only to analyze Elijah Ables’ place in his Mormon community but also within his social, economic, and political communities, whether he was serving a mission in Ontario, crossing the plains, or playing as a minstrel in the northern Utah communities.

For example, we have long known that in 1839, some of Ables’ missionary associates criticized Ables to Jedediah M. Grant and Joseph Smith, claiming that Ables had wrongly told the Saints to “cross the river St. Lawrence” in a timely manner. Without understanding the political and international context, Grant’s comment is rather cryptic. But government memorandum and contemporary correspondence make clear that Ontario was on the brink of civil war while Ables walked the streets. For nearly a year, a band of rebels under the leadership of William McIntyrie had been plotting to secede from the Commonwealth to ally themselves with the United States. Upstate New York and Vermont harbored secret vigilante groups (calling themselves “Hunters Clubs”) as they smuggled weapons to the Canadian rebels. Ables’ critics were either unaware of the rebel movements or feigned ignorance entirely. In December 1838, President Martin Van Buren sent troops to the Canadian border ostensibly to protect the Americans from the British, though it was the Americans who posed the greater threat to the region’s stability.

These kinds of materials–and others–suggest that Ables had to navigate several interlocking communities. By the end of his life, he had lived in rural settlements of Upper Canada and the slums of Cincinnati. No other scholar has sought to capture the diversity of Ables’ experiences.

A: So the interventions that you are talking about weren’t necessarily created by finding new documents within the archive (such as a diary we never existed) but examining the larger context of Abel’s life?

S: My work also unearthed some new documentation: a letter from a non-Mormon observing Ables during his missionary work in Canada, and a letter from Phineas Young identifying Rees Price–a prominent Cincinnati abolitionist–as a Mormon attending Ables’ congregation Each document has provided important clues about various chapter in Ables’ life. The letter from Canada provides solid documentation of Ables’ preaching activities, mob attacks against him, and the efforts of the white Mormon community to protect him (on one occasion, a white Mormon woman opened fire on a tar-and-feather mob in Ables’ defense).

Self-Publishing

A: I find the idea of self-publishing fascinating. What has been the most difficult and best parts of self-publishing? How did you make up for the lack of an editor?

S: It’s a very taxing but very rewarding experience as well. How did I make up for a lack of an editor? I decided that sleep could be bumped to the “luxury” column of my life. That by far was the hardest part. Jana Riess has recently published a piece about why she is choosing to self-publish her work. I can relate to her feelings: this volume was indeed “my baby.”

Abel in Nauvoo

A: One of the things that I noticed about your book and about the book by W. Kesler Jackson was that they both focused, to some extent, on the first half of Abel’s life. What was the reason behind this focus? Is there more documentation from the first half of Abel’s life?

S: It is noteworthy that the first half of Ables’ life is more dynamic. When Ables became a part of the Mormon community, he forged a special friendship with Joseph Smith durable enough to deflect the criticism of Joseph Smith’s confidantes. Some of Joseph’s close confidantes questioned his judgment: Zebedee Coltrin, Orson Hyde, and more subtly, Parley P. Pratt. The media and politicians had all been blasting the Saints for their friendliness towards the black population. In 1836–only a few months after Ables’ ordination to the priesthood–Governor Daniel Dunklin told W.W. Phelps that it was the Saints’ responsibility to prove that they were not abolitionists. And when Elijah Ables moved to Cincinnati, he moved into a “hot spot” for racial violence; there had been two major anti-abolitionist riots over the previous six years. The first half of Ables’ life is more exciting at least in part because he was a man in motion, constantly entering and leaving communities layered with rich religious, racial, and social dynamics.

After he arrived in Utah, the Mormon position on race had moved rapidly towards a consensus, leaving Ables’ ability to grow within the Mormon community stunted. Brigham Young had made known his opposition to blacks holding the priesthood on at least two separate occasion, and the Territorial Legislature had legalized slavery in 1852. Now married with children, he settled into life as many Mormon settlers did: running a business and raising a family.There were, of course, important moments towards the end of his life. The 1879 conversations he had with church leaders would be the pivotal moment in the establishment of the priesthood exclusion ban for the next century. But in his new community, he found fewer opportunities for ecclesiastical growth. He had no choice but to settle down, hoping that circumstances would change.

A: Interesting. What do the effect of focusing on the first half of Abel’s life is for our understandings of Mormonism and race? As you point out, the Mormon community was more open to racial diversity in the first half of Abel’s life. By focusing on the first half, do we risk creating too comforting a story? Do we have any diaries or evidence about the second half of Abel’s life and how he negotiated his life within the Mormon community on a day-to-day basis. The work of women’s historians like Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has shown how what is seemingly mundane – ironing clothing, soothing babies, etc. – can illuminate the politics of everyday life and provide us with a richer understanding of how race, gender, and class function within the everyday lives of communities. Such a study of Elijah Abel would be fascinating and would help to illuminate what the increasing restrictions on African Americans and other racial minorities within the Mormon community meant for individuals, but I wonder if it’s possible.

S: I’m afraid that is a risk. If we come away thinking that Ables’ life was another adventure tale of daring do: staring down lynch mobs, standing up to racist church authorities, and cracking down on dissenters), it is simply another way of painting a caricature.

In A Midwife’s Tale, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s presents the model for how a historian can transform ordinariness into a fascinating narrative–a feat made possible by the existence of Martha Ballard’s journal. Unfortunately, Elijah Ables did not keep such a journal. The best we can do is piece together his life drawing on the world that he lived in. Some documentation does hint at the nature of his day-to-day activities. We know he ran the “Farnham House,” a hotel that likely catered to non-Mormons passing through the area. Ables moved to Ogden in the late 1860s, making it likely that he interacted with the railroad community predominant in the area. Perhaps there are materials tucked away in an archive that discuss Ables’ place in these communities. Kate Engel has recently published a short article gushing about the need for archival research in a digital age. Though archival research takes time and financial resources, I hope my work demonstrates that there archival research should still be a cornerstone in any work of scholarship.

I have sought to capture the increasing racial anxiety that white Mormon faced during the first generation of living in the Utah territory. In spite of Brigham Young’s blatant defenses of slavery and use of racial slurs, many Mormons–especially on the periphery–did not quite grasp the import of Young’s statements. In 1861, one worried man wrote Brigham Young asking about his own “Canaanite” racial heritage: “I had aplied to three different bishop for an <an> answer & thea [sic] told me they were not able to..answer such a questions as it was something new to them.” Having been embarrassed by racial epithets in his own ward, he asked Young outright: “How far could any legal seed mix with the Canaanite & & then claim an heirship to the priesthood” (Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables, chpt. 6). As a visibly mixed-race man, Ables certainly would have faced overt racism on a day-to-day basis.

Questions about Ideas about Race in Mormonism

Focus on Abel

A: I have two questions here. First, Why do you think so much attention has been focused on Abel recently? Second, You mention in the introduction to the e-book that studying Abel’s life need not be an exercise in finger-pointing or in “white guilt.” Can you explain the genesis of these comments a bit more? What role do you think Abel’s life plays in shaping current discussions about race?

S: Excellent Questions. I?ll answer them separately. First, the conversation about Mormonism and race goes beyond its troubled relationship with the black community, as several scholars such as Max Mueller, Jared Tamez, and Paul Reeve have shown.

Though Joseph Smith had global ambitions at the outset, this early vision for a global Mormonism experienced a pretty short life cycle. Generations of isolation in the Intermountain West ultimately led the Saints to erect what I call an idol of whiteness, partially due to racial assumptions they brought with them and also due to their desire to be integrated into the United States. From the beginning, observers hurled racial epithets against the overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon Mormon people; practicing polygamy only intensified it. By the end of the nineteenth-century, the beleaguered Saints cracked in the face of federal prosecution and, in return, the racialization began to taper off. Whiteness was encoded into the Mormon cultural DNA; in 1893, George Q. Cannon celebrated Utah territorial as a haven for a pure white population. As Paul Reeve has shown, whiteness came a high price for the Mormon population: the end of a marital system and the demise of a former identity.

Now, we’re beginning to see the realization of that vision. Some Mormons are excited about it, some are too busy putting up chairs and making casseroles to think about it, and others are incredibly uncomfortable with it. Seth Perry has argued that the recent push to identify Book of Mormon lands with the Great Lakes region represents a “ripple of nativism, a twitch of insecurity among Americans in a globalizing faith.” Mormons are trying to identify themselves in a social media-defined, transnational world. It is predictable that Mormonism’s racial legacy would play into the conversation.

Now to your second question, Ables’ existence forces Mormons to reconsider their racial assumptions. The narrative arc of Mormonism’s doctrine on race typically suggests that the First Presidency–at some point, somewhere–received a revelation that blacks were not to have the priesthood. The Scriptures department has recently added a heading to Official Declaration #2 acknowledging that “a few black men were ordained to the priesthood” during Joseph Smith’s lifetime–certainly a healthy development. In most discussions, Ables is either evoked as a victim of a Mormon system of oppression or as a “The Good Black” or worse, as “the magical negro” whose primary virtue was his commitment to Joseph Smith.

But such characterizations strip him of his personhood, his right to be a complex man with layered identities and character flaws. Upholding him either as a victim or the silent, unwavering black man does no service to him or his legacy. From the outset, Ables saw himself as a singular figure in the history of Mormon race relations. In his later years, he told church leaders that he was to be “the welding link” between the races and “the initiative authority by which his race should be redeemed.”

At the time he made these comments, his wife had died, and his children, moved away–leaving him as an underemployed carpenter living on the good graces of the local dogcatcher. For over fifty years, he had struggled fit into the Mormon community. Alienated from his family, Ables left on one last mission, a mission that would bring him to his deathbed. Yet Ables still believed that he would play a central role in Mormonism’s racial narrative. As the past forty years have shown, he was right.

A: I can certainly empathize with the desire to make Abel into a more complex character and to move beyond stereotypes which flatten him into a paragon of virtue or just a victim of oppression. A lot of work has been done in African American, Pacific Islander, Latino, and other histories to show how people negotiated their worlds in complex, often contradictory ways. One of the things that I wonder about, however, is the “politics” of creating Abel as a “bridge.” In 1981, Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga published an anthology about women of color and queer identity titled “This Bridge Called My Back.” One of the things they pointed out was that it was people of color, not white men and women, were constantly expected to be mediators and bridges. They spoke quite meaningfully about how exhausting the work of creating bridges and working to develop relationships between communities was and wondered when white people would take up the task with equal vigor. Although the focus of the book was on contemporary politics, they do extend their critique to historical figures and the desire to create a multicultural history. They argue that often in our attempt to focus on exchange, interaction, etc. between different races and cultures that we elide structures of power. I worry that to some extent historians are committing the sins that Anzaldua and Moraga outline in their book when they speak about black Mormons like Abel and Jane Manning James.

S: Indeed. In the work, Myne Owne Ground, T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes came under some criticism for their “transactional” portrayal “servant”/slave and later slaveowner, Anthony Johnson. They argued that Johnson’s racial identity allowed for a “fluid set of possibilities” in seventeenth-century Virginia. We do not say such things of nineteenth-century white figures, largely because the power structure was already predisposed to favor them.

Yet the expectation for Ables to be the lone transactional figure surely is not fair to him. In order for any minority to survive in a nineteenth-century white society, s/he needs allies. How did Ables cultivate such relationships? As I’ve traced Ables’ life, I have hoped against hope to discover white figures willing to meet him on his own proverbial ground. Given Joseph Smith’s avid support for Ables, it might be tempting to see him as such a figure. But in spite of Joseph Smith’s relative inclusiveness, it’s clear that he was not willing to risk being called an abolitionist again. Joseph Smith did have to negotiate various factions within the Mormon community, but the ghosts of Jackson County always warned Joseph against embracing the plight of black Americans too closely.

A possible candidate is a figure prominent in modern Cincinnati but has eluded the most scholars’ tellings: Rees E. Price. He joined the Cincinnati Mormon community in spring 1842 within a few months of Ables’ arrival. He had been a member of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society executive board since 1836 and was the close associates of famed abolitionists like John Rankin and James Birney. His passion for abolitionism was matched only by his wealth, prominence, and eccentricity. Cincinnati had erupted in anti-abolitionist riots twice during Price’s tenure on the board. In June 1843, some apostles directed Ables to restrict his preaching to the black community; by January 1844, Price had left the faith and begun his own movement. For the next fifteen years, he identified himself as a “theocrat” committed to bringing down the United States, a country so infected with slavery that he felt that democracy as a system had failed. There is an elementary school named in his honor standing in Cincinnati today. Whether he in fact served as a “bridge” figure is a topic addressed in greater detail in chapter four of my book. In some ways, I hope my work captures the racial radicalism in of Mormonism that appealed to men like Rees E. Price.

A: Well, this is getting a bit long. Perhaps it?s best to cut it off here and let a discussion begin with the readers.

I really enjoyed this, Amanda and Russ. I think the interview was a great idea to format the discussion.

Russ, how do you see the study of Ables expanding our knowledge of 19th century race within Mormonism? I agree that understanding his life and times is important, but how does your book show what it was like to be black in the 20th century?

Comment by J Stuart — July 17, 2013 @ 9:54 am

Ables’ blackness was the only feature of his life that defined him more than his Mormonism. What makes Ables such a compelling figure is that he lived in a wide variety of racial communities: the predominantly white Mormon settlements of northern Ohio and later, Salt Lake City; the runaway slave communities of Ontario; and “Little Africa” and “Little Germany” in Cincinnati. In order for Ables to navigate these communities, he had to learn how to be “black and (insert identity here).” So what Ables’ life does is show the durability and dexterity required of black members, if they wanted to continue in the system.

What does it mean for 20th-century Mormonism? Mormons are quite fond of the idea of “voices from the dust,” “familiar spirits,” and “lost books.” We enjoy imagining Moroni speaking to us “as if [we] were present, and yet [we] are not.” And in a globalizing faith, it’s politically, socially, and most of all, historically correct to revise Mormonism’s racial narrative. Ables demonstrates that the pre-OD#2 world many of us inherited was not ingrained into Mormon theology. So by subverting the narrative, Ables actually makes the narrative more robust–a narrative that shows how a “modern-day Israel” can come to erect their own golden calf of whiteness.

Comment by Russell — July 17, 2013 @ 10:21 am

Thanks, Russell and Amanda, for this fascinating and important exchange.

I’ve been reading through your book the last few days, Russ, and it seems that you’ve walked a fine line trying to balance your multiple audiences (presumably of scholars (both Mormon and non-) on the one hand and lay Mormons on the other. Can you speak to who your intended audience is and how you’ve tried to write a book accessible to both?

Comment by Christopher — July 17, 2013 @ 1:48 pm

I hope to come with questions later, but for now I’ll just say that I loved this exchanged. Thanks to Amanda for the incisive questions/critiques, and to Russell for participating.

Comment by Ben P — July 17, 2013 @ 2:01 pm

Agreed, this was a great exchange.

Comment by David G. — July 17, 2013 @ 2:58 pm

Thanks, both of you.

Comment by Saskia — July 17, 2013 @ 3:13 pm

Chris:

When I took up this project, I decided that the people who needed to hear Elijah’s story the most are the people least inclined towards reading scholarship on Mormonism. So when I imagined the “Brother/Sister Peterson”/”lay Mormon” audience, I imagined several of my family members–loving and committed parents who contribute freely to their communities. Elijah’s commitment to the faith was impeccable, and that was a story that I believed they would find useful.

In order to accomplish this, I drew on the approaches of scholars such as J. Kameron Carter and T.H. Breen. I felt it most important to convey to readers the promise–and tragic outcome–of Mormon race relations in the nineteenth-century.

I could not write it merely as a hagiographic “faith-inspiring” story of a man who was faithful against-all-odds, especially if I was unwilling to discuss the nature of the odds. If I did, I would be denying a defining part of Elijah’s life experience. Both Elijah and modern Mormons deserve better than that.

Comment by Russell — July 17, 2013 @ 4:14 pm

As a missionary, did Elijah Ables preach only or mostly to Blacks? How was the racial dynamics of his missionary services?

Comment by Antônio Trevisan Teixeira — July 17, 2013 @ 8:25 pm

Wonderful! Thank you, Russell, for your research and the response here, and Amanda, for the interview. Very much worth reading.

Question: I don’t know much about e-readers (I guess I could ask my kids) but is it possible to purchase the book in Kindle format and read it on a Mac or PC or other device? And is it very difficult to publish in Kindle format? (Once the writing and editing is done, I mean.)

Comment by Amy T — July 17, 2013 @ 9:02 pm

Antonio:

An important question…one I discuss at some length in my book.

The short answer is that it depends on the time period. During his Canadian mission, he almost certainly preached to a diverse audience of British settlers and runaway slaves (Ontario was the #1 site for runaway slaves in North America). In Cincinnati, church leaders eventually requested that he restrict his preaching to the black population. There had been anti-abolitionist riots twice in Cincinnati’s recent history, and church leaders were haunted by the ghosts of Jackson County. That a hardline and high-profile abolitionist had recently joined the Cincinnati Mormon community put them in an even more difficult position.

Comment by Russell — July 17, 2013 @ 11:54 pm

Did you initially plan on having this published, distributed, and marketed by a publisher or did you plan on self publishing from the beginning of the project?

Comment by John K. — July 18, 2013 @ 8:15 am

Amy T.-

Yes, you can read any Kindle book on your Mac or PC. See here for more information.

Comment by Christopher — July 18, 2013 @ 10:20 am

How much did the Mornons’ leader, Joseph Smith, have to struggle to ordain a black elder (Elijah Ables)in the XIX century?

What kind of impact did Elijah Ables priesthood have in the Mormon community nation and worldwide?

Comment by Graciela Bravo — July 18, 2013 @ 1:08 pm

Thanks, Christopher. I just bought the book, and between that and the newest JMH and finishing the recently published All That Was Promised: The St George Temple (Yorgason, Schmutz, Alder) I should have plenty of summer reading.

Comment by Amy T — July 18, 2013 @ 1:47 pm

Graciela:

Joseph faced an uphill battle. We have at least two of his close associates (Brigham Young was not one of them until 1848-1849) opposing Joseph’s close relationship with Elijah specifically or African-Americans generally. In 1839-1840, Parley P. Pratt tried to downplay (for reasons discussed in the book) the presence of black people in the Church. So Joseph’s support of Elijah Ables did not come without its costs.

Comment by Russell — July 18, 2013 @ 1:48 pm

Thanks to Russell and Amanda for this interesting and important conversation.

Comment by Max — July 18, 2013 @ 6:18 pm