Thomas Tubbs received a BA in English from Western Washington University in 2017 and a MA in Religious Studies from the Vrije University Amsterdam in 2020. His research focuses on religion in America, and the intersection between religion and popular culture.

John Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith is one of the most popular works about Mormonism, and religion in general. The book, as far as I can tell, is not well-regarded in academia. In terms of academic writing on Mormonism, Krakauer seems unlikely to ever be regarded with the likes of Richard L. Bushman. However, the book remains very popular among general audiences. At the time of writing, Under the Banner of Heaven is the second best-selling book in the category “Religious Groups & Communities Studies” and the 3rd bestselling book in the categories “History of Christianity” and “Sociology & Religion” on Amazon.com.

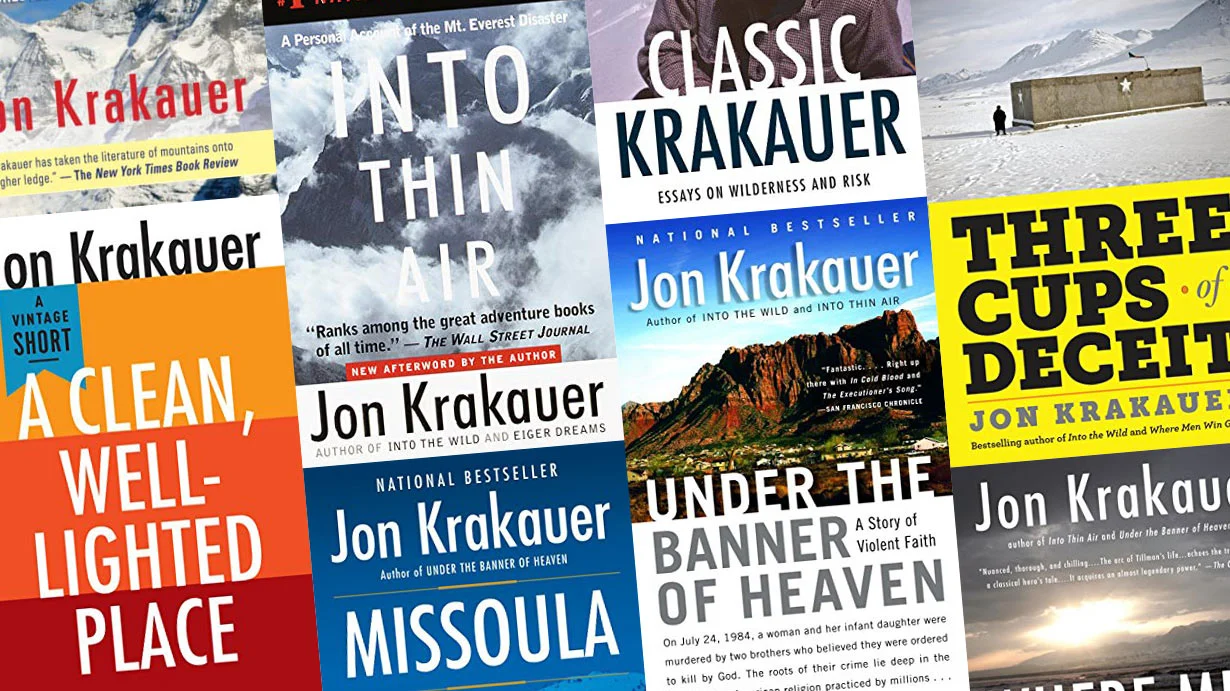

Parts of the book are exceptional examples of the true crime genre, telling the story of brothers Ron and Dan Lafferty, Mormon fundamentalists who committed a gruesome double murder in 1983. This section is in line with Krakauer’s other best-known works, Into Thin Air, an account of a disastrous Mount Everest expedition, and Into the Wild the story of ill-fated adventurer Christopher McCandlass. Krakauer’s background as a journalist made him fairly well suited to cover the Lafferty brothers.

However, in the sections on LDS history and Mormon fundamentalism, Krakauer’s lack of expertise is glaringly obvious. The sections on LDS history are fine enough I suppose, as he managed to at least avoid the trap of only reading Fawn Brodie (I have noticed for many Evangelical critics of Mormonism, their research begins and ends with No Man Knows My History). While his sections of the history of Mormonism could have been worse (I would never recommend Krakauer over Bushman), it is the sections on Mormon fundamentalism that are my biggest issue with the text. What frustrates me, as someone with a background in religious studies, is that Krakauer talks quite a bit about fundamentalism, but never describes exactly what it is, or explores why fundamentalism exists.

What frustrates me, as someone with a background in religious studies, is that Krakauer talks quite a bit about fundamentalism, but never describes exactly what it is, or explores why fundamentalism exists.

Fundamentalism, as a phenomenon, is something that many people talk about, but few understand. Fundamentalism is often associated with the Christian right, used interchangeably with more conservative traditions like Baptists or Evangelicals. And while it is true that fundamentalists exist within Evangelical and Baptist traditions, not every Baptist or Evangelical is automatically a fundamentalist, nor is every Christian fundamentalist a member of those two traditions.

It is important to note that Under the Banner of Heaven came out in the aftermath of 9/11. When I was first reading Under the Banner of Heaven it was glaring to me how much this book was a product of its time, the September 11th attacks and the early days of the war on terror. Under the Banner of Heaven was published a mere two years after 9/11. The attacks were still fresh memory in the American psyche, and Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism was a frequent talking point of academics political commentators. It was around this time, that the new atheist movement began to arise, led by figures like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris who often suggest that the September 11th attacks, and other acts of terrorism, would simply not exist in a world without theism.

The book’s subtitle A Story of Violent Faith seems to reference this mindset. Indeed, Krakauer appears sympathetic to this viewpoint, alluding to it throughout the text, as well as mentioning his own biases against religion; he quotes Bertand Russel’s famous Why I am not a Christian as the epigraph to one of the chapters. Faith for Krakauer, is something inherently irrational, that leads people to do irrational things, such as the horrific crimes committed by the Lafferty brothers. He writes in the introduction to the book “Any attempt to answer such questions must plumb those murky sectors of the heart and head that prompt most of us to believe in God—and compel an impassioned few, predictably, to carry that irrational belief to its logical end” (XXI).

While there is plenty of room for discussion on the rationality of faith (which has been argued about as far back as Plato), Krakauer’s implication that theism of all kinds eventually leads to violence is misguided, or at least does not take into account the history of fundamentalism and why it exists as a phenomenon. Krakauer seems to believe that fundamentalism, and the acts of violence that are associated with it are a natural evolution of religion, an unavoidable final stage of theism. At one point Krakauer compares Colorado City, then a stronghold of the FLDS, to Kabul under the Taliban. While both groups are fundamentalists, I would argue fundamentalist Islam arose from a very different set of circumstances than the FLDS, rather than the shared link of both being ran by theists. However when religious fundamentalism is examined, specifically its history, one may be shocked to find it is mostly a modern development.

While Christian fundamentalist positions, specifically the inerrancy of the Bible is assumed to be as old as theism itself, that is not the case. Even Saint Augustine argued that we should not assume creation occurred over a Creation week consisting of of six literal days. While more theologically conservative strands of Christianity have always existed, “fundamentalism” did not arise until the early 20th century. In 1910, brothers Lyman and Milton Stewart, published a series of pamphlets called The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth. These pamphlets collected writings of various conservative Christians, written in response to various modern developments in theology, specifically higher criticism. Higher criticism broadly speaking is applying contextual and historical research methods to the Bible, and letting go of ideas like the literal history in Genesis, or that Paul of Tarsus wrote every letter attributed to him in the Bible. It is through higher criticism that cornerstones of modern biblical scholarship first appeared, such as the multi-source theory for the composition of Genesis or the Q hypothesis for the formation of the Gospels.

The Fundamentals were written in direct response to ideas like this, as well as more liberal theological attitudes, such as ecumenicism and increased roles of women in church. While Spinoza is considered the progenitor of higher criticism, the movement did not really gain acceptance until the 18th century. Likewise, while the history of Islamic fundamentalism is complicated, it can be traced to various reactions to western influences on Islam and the Arabic world. Sayyid Qutb, for example, was an early figure in what would become the Jihadist movement, developed many of his theological and political positions in direct responses the modernism he encounter during a trip to America, as well as the influence of modernism on the Arab world.

I argue that fundamentalism, and any discussion of the subject, must take into account the fact that fundamentalism is a modern phenomenon and a reaction to specific modern developments. This is something that Krakauer hints at, but never outright says. He comes close to describing why fundamentalism exists, but never explores the subject in a meaningful capacity. He mentions near the end of the book, noting that if the LDS leadership continues to mainstream the Church, that alienated conservatives will leave to seek more extreme groups, and that the FLDS and other fundamentalist groups look for these people. This is as close as Krakauer gets to properly discussing fundamentalism, and by the time he actually does the book is nearly over.

I find it unlikely that anyone who’s first exposure to religious fundamentalism, outside of a cable news story, is Under the Banner of Heaven would pick up that fundamentalism is a response to modernism, and I find that rather concerning. What initially drew me to the field of religious studies was taking a class on religion in India my sophomore year of college, and realizing that most of my preconceived notions about Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism where inaccurate. I expected this to a degree as some popular works about religion are obviously polemical in nature. For example, Robert B. Spencer is an anti-Islamic author who rose to prominence after the 9/11 attacks. His books have titles like The Truth About Muhammad: Founder of the World’s Most Intolerant Religion or The Myth of Islamic Tolerance, and from them alone, one can easily conclude Spencer is not writing from an unbiased position. However, a book doesn’t have to be polemical to be inaccurate, as even well intentioned works which strive to avoid western bias have been rife with inaccuracies. Rather, I want people to know what they are talking about when they criticize a religion, and that fundamentalism does not arise in a vacuum. Simply reading the Koran did not cause the formation of ISIS, nor did simply reading The Book of Mormon and The Doctrine and Covenants cause Ron and Dan Lafferty to commit their heinous crimes. [1]

In the introduction of the book, Krakauer writes “It is the aim of this book to cast some light on Lafferty and his ilk. If trying to understand such people is a daunting exercise, it also seems a useful one—for what it may tell us about the roots of brutality, perhaps, but even more for what might be learned about the nature of faith.” (XXIII) However, understanding a religion is a very complicated task, let alone understanding a fundamentalist. The process of learning to understand a religion itself is a long one. When I tell people I have a masters in religious studies, I usually make it clear I do not claim expertise on all things related to religion. I have studied to varying degrees numerous religions of which I am not a member of, such as Islam, Buddhism, Skihism, Evangelical Christianity, and Mormonism. I have scriptures of these traditions, learned their history, and talked to practitioners. However, despite my formal education, I feel hesitant to speak from a position of authority on these religions. Christianity alone contains an enormous variety of traditions, each with their own distinct history, theology, and practices. I feel like I could (with some preparation) give a lecture on the basic tenets of Christianity to someone who knows little to nothing about it. But to get someone to understand how Christianity functions, or any religion for that matter is a far more complicated task.

I feel Krakauer conflated study with understanding while writing this book, as while he read an amount about fundamentalist history, he does not make much of an effort to understand why fundamentalism exists. Anyone can read the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita, the Book of Mormon, or The Bible and draw parallels between various verses, and violent acts committed by members of each faith. This methodology is rather basic, and how I would describe Krakauer’s approach for researching fundamentalism. However, to truly understand a fundamentalist, one must go far deeper than simply reading primary sources and newspaper clippings. One must examine the history of the religion, the history of the region the religion was practiced in, and any persecution or oppression faced by believers. One must take into account the forms of textual hermeneutics used by these fundamentalist, and how it difference from more orthodox readings. Under the Banner of Heaven feels like a missed opportunity in religious education, as in the right hands, an investigation of the motives of Ron and Dan Lafferty could be chilling but also provide a fascinating insight into the nature of fundamentalism. Instead we are left with an uneven book that feels like a relic of the cultural panic of the 2000s.

Comments

Be the first to comment.