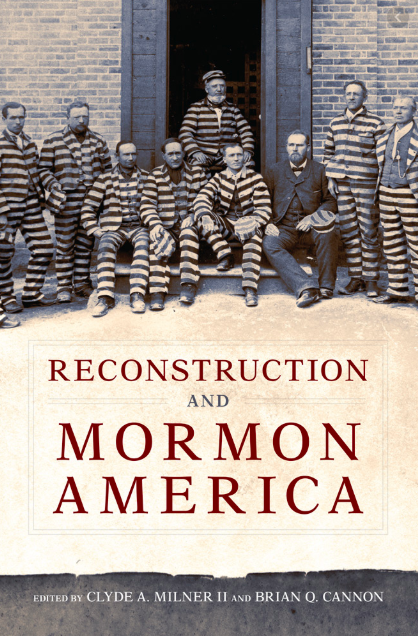

Brian Q. Cannon and Clyde A. Milner II, eds., Reconstruction and Mormon America (University of Oklahoma Press, 2019).

In his 2002 presidential address for the Western History Association, Elliot West argued that American historians needed to think more broadly and holistically when considering race in the nineteenth century. The conflict between North and South over slavery that led to the Civil War was not the only problem surrounding race that vexed D.C. politicians. He writes:

At the moment we took the most dramatic step in our history toward racial justice, freeing one nonwhite people from slavery, we were gathering up skulls of another, and doing it on the premise that this nation was composed of starkly defined races that learned men could tabulate into an obvious hierarchy from best to worst. (1)

Six years later, West explained this further by arguing for what he called a “Greater Reconstruction” that spanned from the annexation of Texas in 1845 to the United States defeat of the Nez Percein 1877. (2) During this period, the United States government tried to assert power over two separate and simultaneous processes: successionist claims of the South over the institution of slavery and westward expansion in spite of the host of sovereign people occupying those lands. Greater Reconstruction thus implies both the expansion of federal power and the ways it strove to incorporate and exclude racial and religious others from citizenship. West argues that Reconstruction is best understood under a broader frame that incorporates federal actions in the West as well as the South.

Mormon Reconstruction takes West’s claims and tests them against the historical experiences of Mormons in the West during the nineteenth century. In doing so, this slate of well-accomplished scholars – in both Mormon history and Western history – tests Reconstruction in the West more generally to see how the idea of Greater Reconstruction works on the Mormon case. The essays in the edited collection come from the contributions and discussion from a 2017 seminar held at the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University.

The most compelling chapters of the bookare the ones that explicitly define (and problematize) the relationship between Mormonism and Reconstruction. Patrick Mason, for example, questions whether the term Reconstruction can be applied to a religious culture still in construction. Rachel St John builds on Mason’s critique of Mormon (re)construction and argues that the term loses its meaning when used to expansively cover both the South and the West. Reconstruction in the South occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War and the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. It was a rebuilding effort for a nation fractured over slavery. In the West, however, the federal government was still working to establish its authority. The federal government was still building its presence in the West as it was Reconstructing its presence in the South.

Elliot West and Rachel St John offer divergent methods. West urges historians to consider Reconstruction as a national project that took different forms in the West and the South; only then, he says, can we understand the contradictory relationships the state created as its power grew over the course of the nineteenth century. St John, by contrast, wants historians to get specific about what Reconstruction is. Does Greater Reconstruction entail a particular kind of state building and population control? Have we stretched Reconstruction’s time period so far that its boundaries no longer have a distinct meaning? Answering these questions, St John argues, shows that the connections between the history of the West and the South become “both too historically specific and insufficiently broad to encompass the diverse and far-reaching processes of state formation, nation building, colonization, and subordination of racial and minority groups that shaped North America in the nineteenth century.” (188)

If specificity is the goal, applying Mormon history to the already nebulous term of Greater Reconstruction creates another problem. What period of nineteenth century Mormon history merits the term Reconstruction? Authors of the volume seem undecided on this question. Angela Pulley Hudson engages with the idea of Mormon expulsion in the 1830s and 40s as potentially part of the Reconstruction experience. The majority of the authors focus on the Utah War in the late 1850s as the main period of Mormon Reconstruction. Meanwhile, I was surprised to find little explicit discussion of the 1880s when the federal government cracked down on the enforcing laws criminalizing polygamy (a period that legal historian Sarah Barringer Gordon called “Second Reconstruction”). (3) This multiplicity of moments in Mormon history (spanning fifty years) represents a whole array of interactions with the federal government. During these fifty years both the federal government and Mormonism as a movement changed and grew immensely. What does it mean then to speak collectively about a Mormon Reconstruction that references all these different moments?

What this book does best is model how historians of different backgrounds can come together disagree on a concept in a productive way. The diversity of the chapters give us a sense of the spirited debate that Brian Q. Cannon and Clyde A. Milner II fostered during their symposium. The idea of Reconstruction and Mormonism’s place inside it is never taken for granted in this book but something that authors can discuss, expand upon, and question.

(1) Elliott West, “Reconstructing Race,” Western Historical Quarterly 34, no. 1 (February 1, 2003): 20.

(2) Elliott West, The Last Indian War the Nez Perce Story, Pivotal Moments in American History (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

(3) Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002) 144.

The lack of discussion of the 1880s is a lost opportunity for the authors of this book, for a few reasons. Firstly, Mormons explicitly saw the conflict between them and the federal government through the lens of Reconstruction politics. They referred to federal agents as carpetbaggers and created political ties with Southern politicians based on a shared sympathy from this experience. Additionally, the raids of the 1880s (and 1890s) represent an opportunity to broaden the Mormon element of Reconstruction beyond just Utah. The mass imprisonment of Mormon men occurred not just in Utah but also in Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, and Wyoming.

“President Johnson’s Utah War of the late 1850s”?

Did you confuse the name of the commander of the U.S. army Utah expedition (Albert Sidney Johnston) with Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor and President at the beginning of post-Civil War Reconstruction, and somehow manage to erase James Buchanan completely from the historical record?

Comment by Mark B. — May 8, 2020 @ 12:47 pm

Hi Mark – thanks for catching that. I have edited it for clarity. I am not, however, too worried about James Buchanan getting completely erased from the historical record by my mistake.

Comment by Hannah Jung — May 8, 2020 @ 1:45 pm

Thanks for the review, Hannah!

Comment by Jeff T — May 8, 2020 @ 2:03 pm

Super sharp, Hannah. Thank you!

Comment by J Stuart — May 8, 2020 @ 2:12 pm

Great review, Hannah! I need to read the book, especially the article by St. John. Good point about the 1880s at the end.

Comment by Erik Freeman — May 15, 2020 @ 7:52 pm