The most recent issue of The Journal of Mormon History (January 2021) includes “’I Dug the Graves’: Isaac Lewis Manning, Joseph Smith, and Racial Connections in Two Latter Day Saint Traditions,” an article by Paul Reeve. One important contribution of this article is information about rates at which adult men in the Latter-day Saint tradition were ordained to priesthood offices up to the early Utah period. Come to find out, in branches of the church, very few men were ordained, and in 1850s Utah ordination was far from universal. Thus the fact that a black man like Isaac Manning doesn’t appear to have been ordained can’t really be evidence for or against any particular race-based approach to ordination. Most Latter-day Saint men during this period appear to have not been ordained.

Paul does a good job at ferreting out data for various locations from 1835 to 1854 (see pp. 44-45). I recently stumbled on the 1853 Bishops’ Report published in the Deseret News [n1], and two half-yearly English conference reports from 1853 [n2]. Consequently, I am going to supplement Paul’s publication with an analysis of this data covering 54 of the 56 wards in Utah (shame on the Mountainville, and Tooele bishops for not getting their reports in) and 55 branches in England. A couple of things to remember:

1. Only rarely did church leaders ordain young men to priesthood offices at this time. Men filled all Aaronic, and Melchizedek Priesthood offices.

2. The report includes “Number ordained,” “Number of members not ordained,” and “number of children,” and various sub-categories.

3. From this we can calculate the percentage of adults ordained in each ward. If you want to estimate the percentage of men in each ward ordained double the number (or divide by 0.5, however you want to get your maths on). Paul used 0.53 for his analysis of the 1854 10th Ward (see p. 45n49), so 0.5 would be more conservative.

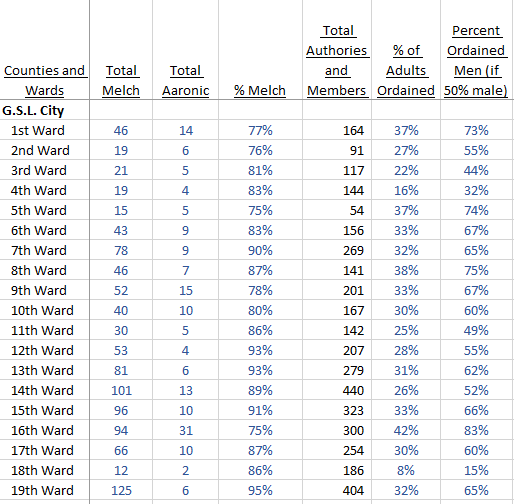

We can’t show all the data comfortably in a blog post, but here is an extract of the priesthood and membership data for the Salt Lake City wards:

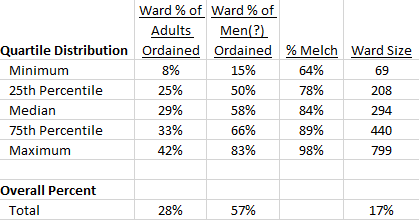

Here is a quartile distribution for various categories, and overall percentage of adult Utah Ward members ordained (and never mind the percent ward size, that was a mistake):

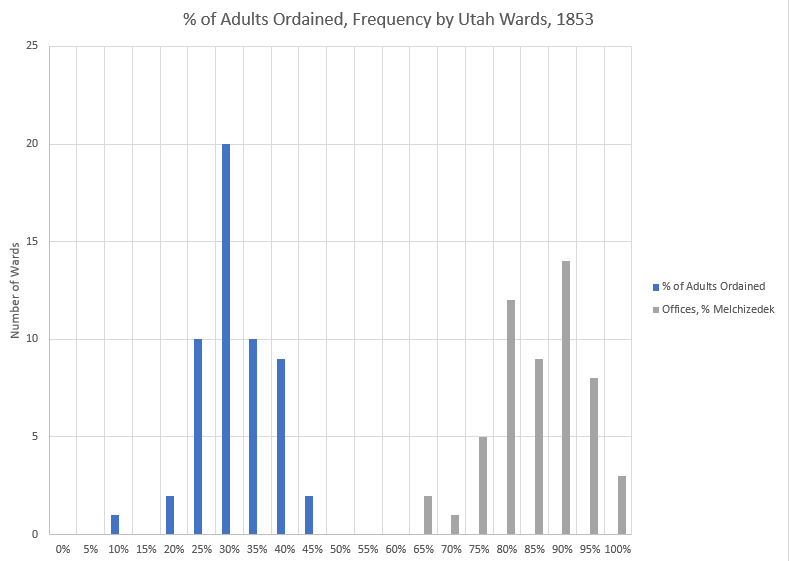

Lastly here is a histogram that tracks the number of wards in Utah by percentage of adults ordained, and also by % of ordinations being to a Melchizedek Priesthood office. So, for example, 20 wards have between 25-30% of their adults ordained:

There is a lot to observe here. I have no idea why the 18th Ward is such an outlier with only 8% of its adults ordained. Still with a statewide adult ordination rate of 28% (57% of estimated male ordination), we can see a fairly normal distribution of the wards around that. Paul estimated that between 54% and 68% of the men in the 10th Ward were ordained in 1854. In 1853 I estimate 60%, which is pretty great corroboration.

The percentage of ordinations that were to Melchizedek Priesthood offices varied considerably. During this period, the Presiding Bishop Edward Hunter complained of Aaronic Priesthood officers getting poached by the Seventies Quorums. With several wards having no Aaronic Priesthood officers at all, he would seem to have identified a real issue. [n3]

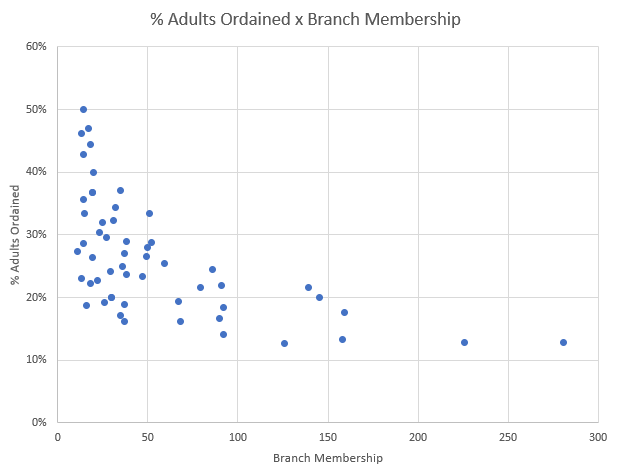

The English data is not normal. That is to say that there are many very small branches of less than 20 members, and ordination rates are very high in those branches. This is perhaps because in order to create a branch with a handful of people, you have to ordain half of them to function. Here is a plot of English Branch size vs. member ordination rates:

From this we can see that there is a sort of standard ordination rate of between 13-25% once the branch gets above 50 members. Conversely, the one branch with 50% of its adults ordained (~100% of males ordained) only had 14 members.

Of the 3,029 members in these English branches, 21% were ordained to priesthood office. 49% of those ordained held Melchizedek Priesthood offices.

And in one final concluding note, I think Paul was correct. If a black or white man wasn’t ordained in the early church, that would make him entirely normal.

_____________________

- “Report of the Bishops,” Deseret News (October 15, 1853), 179. I tried to compare the ward membership data to emigration data in the Pioneer Database, and frankly they don’t line up well. That is to say that wards are smaller than one would expect from the emigration data. I’m, going to trust the Bishops to know their wards for now.

- The CHL uploaded reports for the London Conference, and the Newcastle-on-Tyne Conference.

- My sense is that Early Utah also had inflated Melchizedek Priesthood office ordination rates, because before leaving Nauvoo Brigham Young deftly ordained most the men to the office of Seventy in order to get them out of the control of the stake, and to prepare them for participation in the Nauvoo temple liturgy.

I’ve never thought about this before, J. Really interesting. Thanks.

Comment by Gary Bergera — March 19, 2021 @ 8:23 am

Important collection of data.

One thing that would be important to consider along with this collection of data is where you draw the line for the early church. I assume it would no longer be considered early church when Samuel Chambers was one of the only men active as a deacon in his Salt Lake stake without having been ordained to the priesthood. (That’s based on William Hartley’s work.) Green Flake’s granddaughter recalled that he also performed the duties of a deacon and always had consecrated oil in the house, but also no evidence of ordination.

Where would you draw the line? 1847/1848 when the church headquarters moved to the Great Salt Lake? 1852 when the priesthood restriction began? 1853 when the church compiled this data? The Reformation? 1879? What combination of historical, priesthood, and racial developments would determine the end of the early church period? Is there an accepted historical definition?

Comment by Amy T — March 19, 2021 @ 9:47 am

Thanks Gary.

And those are really excellent questions, Amy. I’m not sure that there is any coherent definition, but I think it makes sense to look at the first thirty years or so of the church as developmentally “early.” So much is in flux and disrupted. That being said, there really are massive differences pre- and post-Nauvoo Temple. There are big differences between 1853 Parowan , UT 1853 and 1842 Lowell, MA.

Comment by J. Stapley — March 19, 2021 @ 10:13 am

Wasn’t the activity rate supposed to have been quite low in the early 1850s? Wouldn’t it be helpful to know how normal it was for an *active* man not to be ordained during this period?

Comment by Nathan Whilk — March 19, 2021 @ 11:50 am

For comparison I looked up the 1978 statistical report (chosen because I could quickly find it in the online April 1979 General Conference report and early enough to include priesthood counts). For 1978, church membership was 4,160,000, and the total of deacons, teachers, priests, elders, seventies, and high priests was 987,000. So 24% of the membership held priesthood office. If we want to subtract off children from the denominator, 97,000 were blessed that year and 63,000 children of record were baptized, so if we subtract off 97,000 x 12 = 1,160,000, it could conservatively be estimated that the ordained were 33% of the membership 12 or older.

Comment by John Mansfield — March 19, 2021 @ 12:54 pm

This is great J. Thanks for sharing this. To Amy’s question I’d say that Bill Hartley made the point that ordination rates likely increased as the 19th century wore on, from the 1860s onward, as more men were called on missions and more men were married in temples, both of which included priesthood ordination. However, it was not until 1908-1922 that the church implemented a system that ushered in nearly universal male ordination when it started to ordain deacons at 12 and created a progression through the ranks for young men. I don’t think that there are clear demarcations before this more systemic revision. I buy Hartley’s argument that rates of ordination, especially in gathering places like Salt Lake City, increased as the century wore on as a result of missions and temple marriages, but that the real changes took place in regard to near universal male ordination between 1908 and 1922.

Comment by Paul Reeve — March 19, 2021 @ 2:22 pm

Nathan, Our conceptions of “activity” don’t map well on to this period. And there aren’t really records that indicate any rates of regular meeting attendance. We know that “activity” rates in this latter sense at the beginning of the 20th century were pretty low, below 20% as I remember. I suspect that 1853 rates of “practicing” according to local expectation were very high.

John, thanks for that. My sense is that would be a sort of apples to oranges comparison, because the denominator in the 1970s would include a very sizable portion of nominally disaffiliated people. The Bishops in Utah and the conferences in England kept pretty tidy house, based on my reading of the records. I could be mistaken of course.

What’s more, I just found a draft version of a 1852 bishop’s report that includes names, and it appears that I may have misunderstood the categories and that instead of adult members it is counting all baptized members in the ward. I’ll probably take a closer look over the weekend and update the post accordingly.

Thanks, Paul. I think that makes sense.

Comment by J. Stapley — March 19, 2021 @ 2:34 pm

A little late to this post. Thanks for sharing, J.

At the end you concur with Reeve that “[i]f a black or white man wasn’t ordained in the early church, that would make him entirely normal.” Makes sense. But then, with these numbers above, is the inverse true, also? Would you say that in the early church, if a black or white man /was/ ordained, that would make him entirely normal? Or is it your view that ordination was something extraordinary?

Comment by David Y. — April 29, 2021 @ 8:27 am