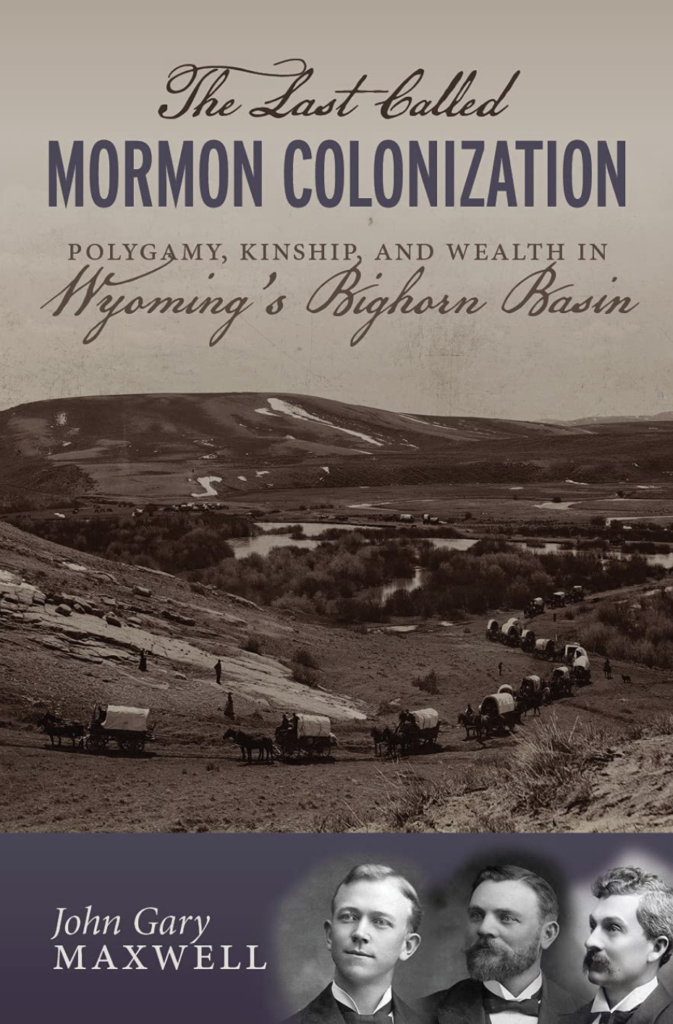

Maxwell, John Gary. The Last Called Mormon Colonization: Polygamy, Kinship, and Wealth in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022.

What motivated Mormon settlers to colonize frontier spaces? Historian Leonard Arrington observed that colonization in the mid-nineteenth century in the American West was a process directed by the church hierarchy. Church President Brigham Young “called” groups of people, often at the semi-annual General Conference, to populate the West. The language of “calling” mirrored the rhetoric about men called on missions. These settlers understood their colonization labor in religious terms; they were not only digging irrigation ditches, but they were also building Zion.[1] These settlers reported back to church leaders and received advice and support from them when needed. After Brigham Young’s death, however, new Mormon settlement patterns were less a product of institutional oversight and more driven by land-hungry settlers looking for decent land.[2] In his most recent book The Last Called Colonization: Polygamy, Kinship, and Wealth in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin, author John Gary Maxwell explores this theme of religious and economic motivations for Mormon colonization. He points to Church leader involvement in the Bighorn Basin and argues that it was the last place that the institutional church “called” its members to settle and represented a potential haven for polygamists.

Maxwell’s discussion of the religious calling of Mormon settlers is limited to the wave of settlers that arrived in 1900-1901. He acknowledges that the Mormon settlers that came to the region before and after did so as volunteers. He shows that Church leaders were interested in the area and promoted its settlement by publishing favorable newspaper articles about the region and assigning apostle Abraham Owen Woodruff to encourage Mormons to settle there. Church leaders also discussed subsidizing settlers railroad travel to Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin.

Yet Maxwell acknowledges later in the book that the First Presidency agreed not to issue “calls from the pulpit” and that many Mormon settlers could have been volunteers based on the positive press that this new area of colonization had received in the press.[3] Thus even his limited sample size of settlers in this small region in Wyoming were more complex than he recognizes in his title. Maxwell does not provide compelling primary source evidence that any settlers in the Bighorn region received a “calling” like they would have in the mid-nineteenth century. While Maxwell recognizes the importance of religiously motivated settlement and the involvement of Church leaders, he neglects to define what “calling” means in this study.

One of Maxwell’s central focuses is what he calls the “disingenuous denials” of Church leaders of polygamy after 1890 Manifesto.[4] Maxwell produces four tables throughout the book that list details about post-Manifesto cohabitation and marriage but does not cite where he obtained this information. In doing so, Maxwell elides some of the central contested nature of primary sources that historians face when looking at this period in Mormon history. His inattention to detail means that he makes mistakes, such as assuming that Matthias Cowley was excommunicated.[5] Maxwell also uses an interview with the current mayor of Cowley, Wyoming to help prove a historical point about the motivation of early Mormon settlers to the region.[6] His first and last chapter, over twenty percent of the book, details the general history of Mormon polygamy. By summarizing the scholarship of past historians, he misses the opportunity to show the details of the lives of polygamous families in the Bighorn Basin region and add nuance to the broader history of Mormon polygamy. The history of Mormonism in Wyoming is still under-developed when compared to other regional histories such as Mexico, Arizona, or Canada. Wyoming is one of the only places in the United States where Mormons talked about feeling “safe” to practice polygamy, particularly after the Manifesto.[7] Indeed Maxwell argues that Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin “was intended to preserve, in frontier isolation, a place to continue plural marriage.”[8] Maxwell shows his readers that polygamous Church leaders encouraged polygamous settlers to colonize the Bighorn Basin but he fails to show why that region fostered (and to some extent still does) polygamy. By prioritizing the history of the institutional church, he misses the opportunity to tell us a unique regional history of the geographic, political, and social conditions that made Wyoming a safe place for polygamists. We still need a history of Mormons in Wyoming that focuses on the politics of Cheyenne rather than Salt Lake City.

[1] Leonard J. Arrington and Ronald W. Walker, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-Day Saints, 1830-1900, New Edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1958).

[2] Richard Sherlock, “Mormon Migration and Settlement after 1875,” Journal of Mormon History 2 (1975): 53–68.

[3] John Gary Maxwell, The Last Called Mormon Colonization: Polygamy, Kinship, and Wealth in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022), 96.

[4] Maxwell, 162.

[5] Maxwell, 176.

[6] Maxwell, 96.

[7] Dan Erickson, “Star Valley, Wyoming: Polygamous Haven,” Journal of Mormon History 26, no. 1 (2000): 123–64.

[8] Maxwell, The Last Called Mormon Colonization, 6.

Thanks, Hannah. Your review touches on exactly the reasons I would have for reading such a history, and has helped my decision about whether or not to order the book.

Comment by Ardis E. Parshall — October 26, 2022 @ 4:34 pm

I was completely unaware that there was actually a community in the US where it was “safe” if still illegal to practice polygyny after Manifesto 1. In 1900 my great-grandfather went to Mexico ostensibly to take a new job but in reality to marry a young girl from his Salt Lake ward where he’d been her SS teacher for the past 5 years. His first wife and children were in a state of shock when they arrived in Colonia Dublan in Mexico and realized what he’d done. They couldn’t return to the US because they were already too poor and because most of his money went to his other family. It would’ve been so much better for his first wife and family if they’d been able to go to Wyoming where there would’ve been a way for them to quickly return to Salt Lake City once they realized what the situation was. Much of the emotional trauma that tainted four generations of my family could’ve been avoided if they had just moved to the Wyoming polygamous community instead of being stuck in Mexico until Pancho Villa was on the warpath and then having to face incredible dangers while being forced to walk the entire way back to the US border while the other family took the train to El Paso.

Comment by A Poor Wayfaring Stranger — November 6, 2022 @ 11:39 pm