By GuestNovember 20, 2013

This installment of the JI’s Mormons and Natives Month comes from Paul Reeve, associate professor of history at the University of Utah and frequent guest blogger at the JI.

In every instance where Mormons faced growing animosity from outsiders and tension escalated between Mormons and their neighbors, accusations of a Mormon-Indian conspiracy were among the charges. The Mormon expulsions from Jackson County, Missouri, from Clay County, Missouri, and from the state of Missouri altogether, along with their exodus from Nauvoo, Illinois, and the later Utah War were all events notably marked by claims that Mormons were combining with Indians to wage war against white America.

Outsiders did not always see war and conspiracy, however, when they conflated Mormons with Indians. Sometimes the conflation was in the search for a solution to the Mormon problem. Such was the case in early 1845 as residents of Hancock County, Illinois cast about for a resolution to their increasingly untenable situation. As my contribution to JI’s Mormons and Natives theme month, I offer below an excerpt from my book project, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford). It describes a little known effort following the Murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith to find a peaceful resolution to the tension between “old settlers” in Hancock County and the Mormons. It is an interesting episode in its own right; but beyond the details of the story, larger themes emerge, a tangled weave of Mormon and Indian threads which outsiders sometimes used to blur the distinction between the two groups and justify discriminatory policies against both.

Within seven months of the murder of the Smith brothers, one minor political figure, William P. Richards from Macomb, Illinois, fifty miles East of Nauvoo, offered a potential solution to the mounting tension between the Mormons and Hancock County residents. In February 1845, Richards proposed a plan patterned after the Indian Removal Act (1830) from the previous decade. This time the correlation between Mormons and Indians moved in a new direction, toward a potential resolution of the Mormon problem that was based upon the Indian solution. In light of the continuing strain between Mormons and outsiders, a condition that Richards believed was “on the very eve of violent and bloody collision,” he offered a plan. His proposal called for a land “Reserve to be set apart by Congress for the Mormon people exclusively,” a place where they would be “safe from intrusion and molestation.” He called for a twenty-four mile square section of land, North of Illinois and West of Wisconsin, bordering the western edge of the Mississippi River, to be “forever set apart and known and designated as the Mormon Reserve.” With a design reminiscent of Indian reservations, Richards’ proposal authorized the president to appoint and the Senate to ratify a “superintendent” to administer the reserve and ensure that only Mormons settled there. They would be allowed to draft a constitution for themselves, so long as it did not violate the U. S. Constitution, and thereby enjoy a measure of freedom and self-determination.

As the proposal circulated locally, Richards defended it and met with Mormon leaders to cultivate their favor. The initial response from the Mormons was positive, although one leader believed that twenty-four square miles was inadequate space for the growing number of Mormons. Richards was not opposed to a larger reserve or to other potential locations in Oregon, Texas, or land west of Indian Territory.

In making his case, Richards noted that the Indian Removal Act established a precedent for such a land reserve. It was a policy for the Indians that he deemed “at once enlightened and humane.” It moved them to a country where they were “secure from future intrusion” and put them in possession of homes that were “sure and permanent.” Richards admitted that it was “not very complimentary to the Mormons to place them in the same category” as the Indians, but his focus was upon a peaceful solution to the Mormon problem and he believed that the example of Indian removal offered exactly that. As he saw it, removing the Mormons to land “set apart for their exclusive occupancy and use” would eliminate the threat of outside persecution. With persecution eliminated as a binding force among Mormons internally, Richards predicted “their present rampant religious zeal would evaporate in a single generation and the Sect as such, become extinct.” If they stayed at Nauvoo, he feared the opposite, “constant turmoil, collision, outrage and perchance,–extensive bloodshed.”

It was an echo from President Andrew Jackson’s justifications for the Indian Removal Act (1830). Jackson, in his 1830 State of the Union Address, argued that providing the Native Americans land West of the Mississippi River and far removed from outside interference was a humane option designed to save the Indians from extinction. “The waves of population and civilization are rolling to the westward,” he argued, and the Indian Removal Act would send the Indians “to a land where their existence may be prolonged and perhaps made perpetual.” To save the Indian from “perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home.”

Beyond a period of local discussion and debate, Richards’ plan did not generate enough interest nationally to garner serious consideration. It did nonetheless indicate the persistent ways in which some outsiders linked Mormons to Indians, not just as a danger, but also in the search for a solution. It further demonstrated how dramatically Mormons were deemed different, a people so distinct, so potentially hostile to American democracy, that they required physical separation, ostensibly to preserve them from the crush of civilization but in reality to preserve civilization from the threat of Mormon savagery.

Rather than an organized “reserve,” Illinois citizens banished the Mormons to their own fate, an expulsion from “civilization” to a new refuge in northern Mexico among “savage” bands of Great Basin Indians. In light of the earlier accusations surrounding the Missouri expulsions, the Mormons found themselves in an ironic bind. As Brigham Young put it, Missourians had accused them of the “intention to tamper with the Indians” and so removed them from that state and their relative proximity to the Indians. Then, ten years later, he said, “it was found equally necessary . . . to drive us from Nauvoo into the very midst of the Indians, as unworthy of any other society.” It was an absurd contradiction for the Mormons, one in which they recognized their own marginalization alongside Native Americans, people whom they were supposed to simultaneously stay away from for fear of conspiracy and live amongst for lack of whiteness

By GuestNovember 14, 2013

This installment in the JI’s Mormons and Natives month comes from Corey Smallcanyon. He is a Dine’ (Navajo) Indian from the Gallup, New Mexico area, who grew up on and off the Navajo reservation. He works as an Adjunct Professor with Utah Valley University teaching United States History. His emphasis is in U.S. History, the American West, Utah history, LDS history, Native American and Navajo history. In his spare time he volunteers teaching Navajo genealogy to surrounding areas and spending time with his family.

Among the Dine’ (Navajos) Ma’ii (coyote) stands center stage as a trouble maker, wise counselor, cultural hero, and powerful deity. Ma’ii stories help establish a foundation for the ethical teachings for all children. Early traditional memory tells of Ma’ii who tried to steal the farm of Grandfather Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii (Horned Toad). Ma’ii came “wandering” upon Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii tending his farm and asked for some of his corn to eat. After much begging, Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii gave into Ma’ii’s demands, but Ma’ii was not satisfied and began taking more without permission. As Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii tried to take the corn away Ma’ii ate Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii. Upset with his predicament, Na’asho’ii Dich’izhii was eventually able to make his way out of Ma’ii, and triumphed by taking back his farm.[1]

As Jim Dandy, a Mormon Navajo traditionalist, states that Ma’ii is one of the most misunderstood animals, “He is neither good nor bad, just innocent and trying to understand how everything works,” although he admits his innocence creates problems for people.[2] The enigma known as Brigham Young falls into this dilemma of how to view his Indian policies and treatment of a group who considered themselves as “the People.”[3] As leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Governor of Utah Territory and Superintendent of Indian Affairs; this allowed Young to deal with Natives in three different capacities; which included the creation of a multifaceted program known as Indian farms.

Young oversaw near 100 colonies within the first ten years of reaching the Great Basin. His initial Indian policy was of peace and kindness; but that was overshadowed by his expansion onto choice Native lands, over exertion of limited natural resources, and exploitation of traditional sources of foods Natives relied on.[4] The solution to Young’s Indian Problems mirrored all other Americas with the removal of Natives onto reservations. The culminating issues resulted in armed conflict which was quite costly and fostered in officially his policy that it was cheaper to feed Indians than to fight them.

By 1850, the Trickster wrote Washington D.C. requesting the extinguishment of Indian title to the land, and the removal of Natives to locations outside of present-day Utah. He argued that “the progress of civilization, the safety of the mails and the welfare of the Indians themselves called for the adoption of this policy.”[5] Although his request was denied, mini-reservations were created around 1852 and called Indian farms. Many view these farms as a “policy of cultural integration”[6] to show Natives “a way wherein they could help themselves overcome their destitute condition and become self-sustaining,”[7] but also to monitor their semi-nomadic movement. Young’s Indian farms would be short lived ending around 1859 because they proved to be inadequate or failed completely.[8]

No longer does Ma’ii “wander” around trying to control the Dine’ or take their land. Now he offers a way for “the People” to live in two worlds. In June 2008, the Tuba City Arizona Stake called Larry Justice as its new leader.[9] As other denominations are hurting for converts, Justice helped introduce a modern-day Indian farm program in Tuba City, an area the Church has had a long turbulent history with the local Navajo and Hopi Indians. On October 30, 2013, the New York Times published an article about this gardening program, “Some Find Path to Navajo Roots Through Mormon Church,” written by Fernanda Santos. In 2009, the pilot program was launched and since then the Church has seen a 25 percent increase in membership. The program originally started with 25-30 Church members and has increased to 1,800 gardens with plans of adding 500 more in 2014 with at least 50 percent of the participants being non-Mormons. As a result the Church has plans to expand the gardening program into other parts of the world with hopes of converting indigenous peoples by teaching them “principles of self-reliance and Provident Living, through gardening.”[10] As Santos focuses on the gardening program, Justice stated that the Tuba City Stake has a “two-pronged approach–gardening and family history work,” which is discussed in Samantha DeLaCerda’s article in Church News, “Garden Project in Arizona” written in March 2012.

As for the new Tuba City converts, Santos notes: Nora Kaibetoney (Dine’) states that even though Mormonism compels them to leave behind part of their Dine’ identity, the Church helps enforce Dine’ values of “charity, camaraderie and respect for the land.” Linda Smith (Dine’) stated that joining the Church “wasn’t about turning away and embracing an entirely different tradition; it was about reconnecting.” Sam Charlie (Dine’) also stated that he “went on the LDS Placement Program for four years and never learned how to grow a garden. It has been a wonderful thing to recapture this lost element of our culture.”[11] Justice told reporters that through the garden program, “Navajos connect with their heritage through the land.”[12] I wish there was more of an allowance here to navigate the use of the sacredness of land as a missionary tool among “Native” peoples.

These stories of Ma’ii are not just meaningless folklore. They have great worth to the Dine’ because they express, enhance and enforce the morals and customs of Dine’ society. A “wandering” Ma’ii is a representation of socially unacceptable behavior, but the eventual victory and good fortune of those whom “wandering” Ma’ii tries to trick, cheat or destroy just reaffirms the eventual triumph of justice and morality. As the 21st century Dine’ people try to understand Ma’ii, we become transitional and walk between two worlds. As many celebrate Native American Heritage Month, a unifying theme is a reminder to the world that we are still here. This message applies to Ma’ii and his Indian farms, past or present. As Natives learn to adapt to the 21st century, Ma’ii still is as ambiguous today as he always has been.

______

[1] Robert Roessel, Jr. and Dillon Platero, eds., Coyote Stories of the Navajo People (Rough Rock, AZ: Navajo Curriculum Center Press, 1974), 85-90; Margaret Schevill Link and Joseph L. Henderson, The Pollen Path: A Collection of Navajo Myths (Literacy Licensing, LLC, 2011), 48-49; also see, Shonto Begay, Ma’ii and Cousin Horned Toad: A Traditional Navajo Story (Scholastic Trade, 1992).

[2] Robert S. McPherson, Jim Dandy, and Sarah E. Burak, Navajo Tradition, Mormon Life: The Autobiography and Teachings of Jim Dandy (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2012), 183.

[3] The Shoshone call themselves Newe, meaning “People;” Goshute is a Shoshone word for “Desert People;” the Navajo call themselves Dine’ meaning “the People;” the Northern Paiute call themselves Numa and Southern Paiute call themselves Nuwuvi, both meaning “the People;” and the Ute call themselves Nuciu meaning “the People.”

[4] Young often championed for the needs of local Natives with sentiments like, “Before the whites came, there was plenty of fish and antelope, plenty of game of almost every description; but now the whites have killed off these things, and there is scarcely anything left for the poor natives to live upon,” but his actions usually ended up benefiting his members, which was his main concern. See Brigham Young, “Wilford Woodruff sermon on 15 July 1855,” Journal of Discourses, 9:227.

[5] Deseret News (Salt Lake City), 16 November 1850. Young again asked for the creation of Indian reservations in 1852, 1854, and 1861. President Abraham Lincoln signed an Executive Order establishing the Uintah Valley Reservation in 1861, which was finally signed by Congress on May 5, 1864. Eventually, other reservations would be established for the removal of all Natives in Utah. In 1863, the Shoshones and Goshutes signed treaties for removal, and after years of conflict between the Indians, Mormons, Utah and Federal governments, reservations were established for the Goshutes at Skull Valley in 1912 and Deep Creek in 1914. The Shoshone never received a reservation until the donation of land by the LDS church in 1960. In 1865 the Paiutes also agreed to hand over tribal lands and over years of conflict were given several reservations which included the Shivwits (1891), Indian Peaks (1915), Koosharem (1928), Kanosh (1929), and Cedar Band (1980). The White Mesa Utes signed over tribal lands in 1868 and never received a reservation in Utah and are unrecognized by the federal government. The tribe did purchase lands at White Mesa and some tribal members reside there. The Navajos also signed over tribal lands through the 1868 treaty and were given reservation lands in southern Utah in 1884. See Forrest S. Cuch, ed., A History of Utah’s American Indians (Salt Lake City: Utah State Division of Indian Affairs and Utah State Division of history, 2003), 67-72, 104, 113-19, 139, 141-65, 189-94, 243, 261, 288-90.

[6] Richard H. Jackson, “The Mormon Indian Farms: An Attempt at Cultural Integration” in Geographical Perspectives on Native Americans: Topics and Resources, Vol. 1, (Washington D.C.: Association of American Geographers, 1976).

[7] Frederick R. Gowans. A History of Brigham Young’s Indian Superintendency (1851-1857) “Problems and Accomplishments (July 1963), 39.

[8] Trying to find a solution to his Indian problems, Young attempted to settle Natives on farms established under the watchful eye of Mormon superintendents in 1852. This at least attempted to assist Natives in finding another source of food, but these farms would be short lived, by 1859, conflicts with non-Mormons hindered Mormon interactions with Natives. Federal Indian agents argued that Mormons were trying to influence Natives against the United States and recommend that Natives in Utah Territory then be placed on reservations within Utah Territory, where they could have legal jurisdiction over the Natives (see, David Bigler, “Garland Hurt: The American Friend of the Utahs,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 62, No. 2 (Spring 1994), 149-70). After the Civil War, the conflict in Utah between the Natives, Mormons and non-Mormons brought about the creation of Utah’s first Indian reservation. It was soon found that Young’s Indian farms either proved to be inadequate or failed completely. The idea of Indian farms did pique the interest of the Indian agents and implemented Indian farms among a number of tribes. In part this eventually evolved into the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 (a.k.a. General Allotment Act), which divided Native lands into allotments for individuals with the hopes that Natives would farm their lands and become productive members of white society, with surplus Native lands ending up in the hands of non-Natives (see, Beverly Beeton, “Teach Them to Till the Soil: An Experiment with Indian Farms, 1850-1862,” American Indian Quarterly Vol. 3, No. 4 (Winter, 1977-78), 299-320).

[9] “New Stake Presidents,” Church News (1 November 2008).

[10] Aside from the embedded link, see See Allie Schulte, “Seeds of Self-Reliance,” Ensign (March 2011), 61-65.

[11] Allen Christensen, “Bountiful Garden,” Church News (October 2, 2010)

[12] Tad Walch, “Why are more Navajos joining LDS Church”, Deseret News (October 31, 2013)

Ed. This post has been updated.

By GuestNovember 7, 2013

This installment of the JI’s Mormons and Natives month comes from Matthew Garrett, associate professor of history at Bakersfield College in California. He received his Ph.D. in American History from Arizona State University in 2010. He is currently revising for publication his dissertation, “Mormons, Indians, and Lamanites: The Indian Student Placement Program, 1947-2000,” which should prove to be the definitive history of the ISPP.

When David G. approached me to contribute to this month’s theme, I initially thought the notion of a “Mormons and Natives” field of study seemed a bit odd. I never viewed the two fields with much connectivity, other than a few mid-century works about Jacob Hamblin or Chief Wakara. As I sat down to draft out the separate evolutions of the two fields, the task proved far more complicated than expected, and the only way I could think to articulate it was to take the reader on a semi-biographical journey that follows my own intellectual awakening. I trust that the Juvenile Instructor’s readers will tolerate a little self-indulgence as I relate the divergence and re-convergence of Mormon and Indian history.

My interest in history blossomed on my LDS mission and during undergraduate studies at BYU as I read about pioneers and western heroes such as Porter Rockwell. Like most history buffs, I looked to explorers and battles more than indigenous cultures but I did not understand that my approach mirrored Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis. In 1893, Turner’s nationalistic narrative identified waves of civilizing conquest that ended in 1890 with the settlement of the region by whites. Though essentially silent on Native Americans and Mormons, this foundation served as the methodological origin of Western American history that eventually spawned those sub-fields.

By the mid-twentieth century, Turnerarian history had gained an impressive following of amateur and professional historians interested largely in nineteenth-century topics: mountain men, pioneers, and cowboys and Indians. A new wave of neo-Turnerians gradually focused on individual people and communities, as well as environmental topics; those individual case studies fragmented the monolithic and ethnocentric national narrative.[1] In 1961, the Western History Association organized and soon after began publishing the Western Historical Quarterly (WHQ). Professionally trained Western American historians proliferated over the following decades and other organizations spun off to create even more specific associations, such as the American Society for Ethnohistory (1966) and the Mormon History Association (1965).

Professionally trained scholars including Leonard Arrington, Davis Bitton, and Alfred Bush organized the MHA and laid the groundwork for the New Mormon history; their concern with critical questions and historical inquiry strengthened a field formerly characterized by faith building authors such as B.H. Roberts. Still, they cooperated closely with the Church and the larger Western history field, most evident by Arrington’s service as Church historian, president of the MHA, and president of the WHA.

By the 1970s, recent cultural shifts era had ushered in new academic interests. The New Western History fused social history with environmental history, and eventually redirected the field into twentieth-century topics and oft-ignored ethnic voices. Popular author Dee Brown drew attention to the overlooked victims of longstanding conquest-oriented history in his moving text, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970). Meanwhile, trained scholars including Arrell M. Gibson, Angie Debo, Tom Hagan and others paved the way for a new generation of scholars who inaugurated the New Indian History. This ethnographic approach stressed Native perspectives and tackled tribal histories and other Indian topics across time, including the long overlooked twentieth century. In 1972, the Newberry Library created the D’Arcy McNickle Center as academic institutions opened Native American studies programs and interdisciplinary journals, such as American Indian Culture and Research (1971+), American Indian Quarterly (1974+), and Wicazo Sa Review (1985+). Emerging young scholars fit neatly within the ranks of the equally progressive New Western History.

My introduction to the New Indian history came during graduate studies at the University of Nebraska where faculty mentors pointed me to a new world of Indian driven narratives that explored Native voices and perspectives. Still, I moved forward on an unimpressive thesis exploring colonial Kickapoo foreign policy from European records. The final product resembled an awkward and incomplete transition from the neo-Turnerarian framework that still structured my thoughts. I had come a long way from Turner’s omission of Native Americans, and went to the extent of a minor in anthropology that included four semesters of a Native language, but I still struggled to fully represent indigenous perspectives when dealing with a colonial era population that left no written record of their own.

After completing my degree at UNL, I enrolled in doctoral study at Arizona State to work with two leading figures in the New Indian history. One of the first students I met was two years ahead of me in the program. She was studying under another professor who advocated a radical new approach to Native American history: decolonization theory. I was uninitiated and probably in a bit over my head when this fellow graduate student took it upon herself to expose my inadequacies. She aggressively questioned me, particularly on twentieth-century Indian history where my readings were admittedly the weakest, and then she explained that a white man such as I had no business studying Indian history. In retrospect, she probably assumed my unfamiliarity with decolonization equated to an endorsement of ethnocentric Turnerian history. Nevertheless, her overt racism surprised me because it ran so contrary to my expectations of an open-minded academy. That was my first introduction to decolonization studies, and I would not be honest if I did not confess how much it tainted my view of those who practice that methodology.

In theory, decolonization is an interdisciplinary and deconstructionist approach to reveal the mechanisms of colonization and indigenous resistance by use of overlooked Native voices.[2] In practice, the exclusionary methodology often endows Native voices with extraordinary authority while dismissing traditional sources and scholarship as hopelessly corrupted by ethnocentrism. During the 1990s, many senior historians rejected decolonization-based scholarship in tenure evaluations, manuscript submissions, and conference presentations. The conflict came to a head when decolonization advocates publicly challenged senior scholars Patricia Limerick and Richard White at an academic conference, who then responded with critical roundtables, editorials, and even a T-shirt campaign.[3]

Over the past two decades, dejected decolonization activists turned to non-scholarly presses and produced new interdisciplinary journals to publish their work and assert themselves the authoritative voice.[4] Their following expanded and in 2007 a small group launched the Native Americans and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA). One year later at the annual WHA meeting, Dave Edmunds directed his presidential address to departing scholars. He offered clear examples of the association’s commitment to Indian history but also stood his ground as he criticized “some Native academics [who] have urged that scholarship conform to a new orthodoxy defined through the rhetoric of post-colonialism.” He continued, “We do not need a new cadre of self-appointed “gate keepers.’”[5] NAISA and the WHA continue to hold separate conferences each year attracting a very different type of scholar to each.

My feeling is that decolonization has much to offer. It brings long needed attention to Native perspectives through interdisciplinary inquiry and introduces post modern study of power structures. However, it cannot be permitted to eject non-native voices or impose a simplistic oppressor-resistor relationship on every historical interaction. While it may often apply, few theories have universal application.

These debates have gone largely unnoticed in Mormon studies because the New Mormon history’s attention to critical revision of longstanding nineteenth century topics like the early Church and polygamy, leaving little consideration for Native Americans in the modern era. Juanita Brooks well represented the sharp analysis of the New Mormon history as she addressed Indians, but even her pioneering work remained largely in the nineteenth century and focused on Mormons more than Native cultures they impacted. It lacked the ethnographic nature of New Indian history and certainly the Native voices championed by decolonization theory. Essentially, Mormon scholarship on Indians remains heavily neo-Turnerarian, while Indian scholarship moved through the New Indian history and now faces a challenge from decolonization.[6]

Despite an increasingly common interdisciplinary inclination among Mormon and Indian history scholars, they speak a different language depending upon their point of origin. While practitioners of the New Mormon history are no strangers to difficult questions, I suspect they will be disturbed by the tenor of decolonization advocates. Like any revisionist movement, it brings valuable new criticisms that can be taken to an extreme at the expense of the past.

In the coming years the LDS church’s twentieth-century Indian policy will surely serve as the battle ground between the new Mormon history and decolonization theory. Indeed, the 2013 meeting of the MHA featured what I believe was the association’s first overtly decolonization-driven interpretation of Mormon-Indian relations. My research tries to preempt much of this debate on what is sure to emerge as one of the focal points: the Indian Student Placement Program. This voluntary foster care program for Native American youths operated between 1947 and 2000. While many Latter-day Saints viewed it as a benevolent opportunity to educate deprived Indians, outsiders criticized Placement as simply another assimilation program. Tensions mounted in the 1970s and though external pressures subsided by the 1980s the correlation movement continued to erode the program until the Church prohibited the enrollment of any new students after 1992.

My approach to this topic is to examine the institutional rise of the program, building on the work of Michael Quinn and Armand Mauss but balanced with ethnographic focus on student experiences. Their thoughts are recorded in over one hundred interviews and other sources. While many participants surely resisted colonizing pressures, a great many others internalized the imposed Lamanite identity as their own. Placement students left reservations and spent years immersed among Mormon host families; they attended schools, church activities, and a barrage of Lamanite-specific activities including dances, leadership conferences, and cultural extravaganzas that promoted a hybrid identity. These students’ experiences demand a more nuanced approach than the sloppy imposition of a binary model of aggressive colonizers and resisting colonizees.

As the fields of Mormon and Native history/studies re-converge, interested readers must carefully evaluate scholarship to ensure the narrative is indeed an honest reflection of the past and not an intellectual exercise in bending it to meet theoretical expectations. Long ago the New Mormon history and Western history threw off their allegiances to a single ideological narrative, and to adopt yet another would constitute a methodological step backward. Decolonization theory does have a role to play and we should follow its council to incorporate marginalized voices; however, it cannot be the singularly authoritative approach that its advocates demand. There must be space for alternative forms of analysis and no singular approach can be complete. The greatest strength of the New Mormon history and especially Mormon studies is its aspiration to achieve intellectual independence, and I hope that characteristic remains the dominant attribute among those who study Mormons and Natives.

______

[1] Richard White, “Western history,” The New American History, Revised and Expanded Edition, ed. Eric Foner (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997), 205; Donald Worster, “New West, True West: Interpreting the Region’s History,” Western Historical Quarterly, vol 18 (April, 1987), 141-156. For an example of early environmental work see Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1931).

[2] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (New York: Zed Books, 2005), 3, 20. See also Angela Wilson and Michael Yellow Bird, For Indigenous Eyes Only: a Decolonization Handbook (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 2005); Devon Mihesuah, Natives and Academics: researching and writing about American Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998); Devon Mihesuah and Angela Wilson, Indigenizing the academy: transforming scholarship and empowering communities (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

[3] William T. Hagan, “The New Indian History,” in Rethinking American Indian History, ed. Don Fixcio (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997), 30.

[4] The last ten years has also given rise to open source and other low tier interdisciplinary journals, such as: Canadian Journal of Native Studies (launched in 1981); AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples (2005); Te Kahoroa (2008); Rethinking Decolonization (2008); International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies (2008); Indigenous Policy Journal (2009); Journal of Indigenous Research (2011); Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society (2012).

[5] R. David Edmunds, “Blazing New Trails or Burning Bridges: Native American History Comes of Age,” Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 39:1 (Spring 2008), 14.

[6] For example, over the past year, twentieth century topics constituted only 13% of Journal of Mormon History and 70% of Western Historical Quarterly articles. Likewise, ethnically marginalized individuals or groups were directly addressed in only 9% of JMH articles but in 64% of WHQ pieces. Of course, the JMH is by nature an ethnically specific journal so a broad survey of other ethnic groups is understandably beyond its mission. Nevertheless, their different foci are evident.

By GuestSeptember 27, 2013

Alan Morrell, a curator at the Church History Museum, contributes this installment in the JI’s material culture month. Alan is completing a doctorate in American History at the University of Utah, and he has degrees from BYU and Villanova.

I have an iPhone because I once missed an appointment. I was so engulfed in my research, I forgot about a meeting and didn’t realize it until it was already over. My wife teases me about being absent-minded, but she wasn’t amused when I told her what had happened. After years of marriage to a poor grad student, she was thrilled that I had a paying job. She worried that I’d screw it up so she went out and bought me something that could keep me on track. Now, the time and my schedule are always available, with reminders of upcoming appointments.

In our hyper-connected modern world, we quickly learn to become time conscious. David S. Landes, author of Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World considered the mechanical clock to be “one of the great inventions in the history of mankind: not in a class with fire and the wheel, but comparable to movable type in its revolutionary implications for cultural values, technological change, social and political organization, and personality.”[1]

Historian Alexis McCrossen examined the records of watch repairmen in 19th-century western Massachusetts and observed that “Americans had been living with watches and clocks for decades without fully tapping into the potential they provided for coordination and maximization of time.”[2] This changed in the 1820s when the volume of pocket watches in the United States increased drastically. By the 1840s, the price of a clock or watch had dropped to the point that even a person of modest income could afford one.

John Taylor. Courtesy Wikimedia

This was the world of John Taylor. Born on November 1, 1808 in Milnthorpe, Westmorland, England, he moved to Toronto, Canada, in 1832. Six years later, he was a Mormon apostle. I do not know when John Taylor started carrying a watch. The multiple appointments of a Latter-day Saint leader would have certainly required that Taylor be conscious of the time. The narrative history that Joseph Smith started in 1838 demonstrates that time consciousness was an essential part of the Mormon community. Recorders noted the times of events such as the departure of the “Maid of Iowa” at 10 A.M. on May 1, meetings of Church leaders from 2 to 6 and again from 8 to 10 P.M. the next day, or a court martial at 9 A.M. on May 4.[3]

It is not surprising, then, that on the evening of June 27, 1844, John Taylor was wearing his watch as he sat with Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Willard Richards. The previous days had been busy as he met with the governor, lawyers, and leading citizens in an effort to free the Smith brothers. Readers know the story of the martyrdom. Within minutes, Joseph and Hyrum Smith were dead and John Taylor was severely injured. Taylor described getting shot, “As I reached the window, and was on the point of leaping out, I was struck by a ball from the door about midway of my thigh. . . . I fell upon the window-sill, and cried out, ‘I am shot!’ Not possessing any power to move, I felt myself falling outside of the window, but immediately I fell inside, from some, at that time, unknown cause”[4]. He was badly wounded. Four bullets had ripped through his body, one tearing away a portion of his hip the size of his hand. Willard Richards who escaped the barrage without injury dragged Taylor into a cell, covered him with a mattress in an effort to hide him, and said he hoped Taylor would survive as he expected to be killed within a few moments. The mob, perhaps fearing that the Mormons were coming, fled. Both Taylor and Richards were spared.

John Taylor’s Watch. Courtesy PBS

Willard Richards had John Taylor moved to Hamilton’s tavern and then went about the business of preparing for the removal of Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s bodies. When Richards left for Nauvoo, John Taylor asked him to take his watch and purse with him, as he feared they would be stolen. Several days later, Taylor was at his home in Nauvoo still convalescing when he was once again reunited with his watch. At this moment, the watch was transformed from a mere timepiece to a holy relic. His family discovered that the watch had been “struck with a ball” and examination of his vest revealed a cut in the vest pocket that had contained his watch. He later explained, “I was indeed falling out [of the window at Carthage Jail], when some villain aimed at my heart. The ball struck my watch, and forced me back; if I had fallen out I should assuredly have been killed, if not by the fall, by those around, and this ball, intended to dispatch me, was turned by an overruling Providence into a messenger of mercy, and saved my life.” He concluded, “I felt that the Lord had preserved me by a special act of mercy; that my time had not yet come, and that I had still a work to perform upon the earth.”[5]

The story of John Taylor’s miraculous preservation spread quickly. Within a few weeks, several accounts mentioned that Taylor’s watch had been hit by a ball.[6] The watch become an integral part of the telling of the martyrdom; the story spread wide and far. The relic remained in the family until 1934 when John Taylor’s grandson, Alonzo Eugene Hyde, Jr., gave it to LDS President Heber J. Grant, who forwarded it to the museum at the Bureau of Information, a precursor of the Church History Museum.[7] Since 1990, the John Taylor watch has been on public display at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, a highlight for visitors of the museum’s “A Covenant Restored” exhibit.

By the latter part of the 90s, several individuals began to research and write about their questions surrounding the long-accepted story of the John Taylor watch. They could not believe that a musket ball would do so little damage to a watch. In Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, Historian Glen Leonard cited the unpublished research of Neal and Gayle Ord when he wrote that after John Taylor was first shot in the leg, “He collapsed on the wide sill, denting the back of his vest pocket watch. The force shattered the glass cover of the timepiece against his ribs and pushed the internal gear pins against the enamel face, popping out a small segment later mistakenly identified as a bullet hole.”[8] Joseph L. and David W. Lyon’s 2008 BYU Studies article “Physical Evidence at Carthage Jail and What it Reveals about the Assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith” is probably the most exhaustive published scholarship arguing this position.[9] A couple years later, Joseph Lyon’s scholarship received popular attention after his presentation at BYU Education Week.[10] Kenneth W. Godfrey’s interview for the KJZZ Joseph Smith Papers television series furthered this narrative for a popular audience.[11]

A search of sources, both popular and scholarly, online and in print, shows that both stories are alive and well today. This begs several questions. Has the window sill explanation become the new master narrative for scholars? Has this narrative moved out of scholarly circles into the Mormon mainstream? Does the window sill remove the miraculous from the story? Do some individuals use this as another example of scholars just trying to destroy faith? Is there any evidence of deceit by those who originated or propagated the original story? Regardless of the answers to these questions, we should be grateful that John Taylor believed the watch saved his life. It may be the only reason it is still around. What good is a watch that doesn’t keep time?

______

[1] David S. Landes, Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 1983), p. 6.

[2] Alexis McCrossen, “The ‘Very Delicate Construction’ of Pocket Watches and Time Consciousness in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” Winterthur Portfolio Vol. 44, No. 1 (Spring 2010)

[3] Historian’s Office history of the Church 1839-1882. http://eadview.lds.org/findingaid/CR%20100%20102, Book F1

[4] “The Martyrdom of Joseph Smith” by President John Taylor (http://archive.org/stream/cityofsaintsacro00burt#page/517/mode/2up), Appendix III.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Jenetta Richards letter to her family, 8 July 1844, in Our Pioneer Heritage, vol. 3, p. 130; Times and Seasons 15 July 1844; Nauvoo Neighbor 24 July 1844; and Times and Seasons 1 August 1844

[7] Deseret News, 8 November 1934

[8] Glen M. Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, Deseret Book, 2002, pp. 397-98.

[9] Joseph L. Lyon and David W. Lyon, “Physical Evidence at Carthage Jail and What It Reveals about the Assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” BYU Studies 47:4. https://byustudies.byu.edu/showTitle.aspx?title=7980

[10] “Education Week: Separating Facts from Fiction about the Prophet’s Death,” Deseret News, Sept. 7, 2010, http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705385933/Education-Week-Separating-facts-from-fiction-about-the-Prophets-death.html?pg=all

[11] “John Taylor’s Watch ‘The Real Story” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOlH26SE55k

By GuestSeptember 26, 2013

This installment in the JI’s material culture month comes from Farina King of the Kinyaa’áanii (Towering House clan) of the Diné (Navajo). She is a second-year graduate student in the U.S. History Ph.D program at Arizona State University. She received her M.A. in African History from the University of Wisconsin and a B.A. from Brigham Young University with a double major in History and French Studies. King has written and presented about indigenous Mormon experiences in the twentieth century, drawing from interviews that she conducted for the LDS Native American Oral History Project at BYU. Her doctoral research traces the changes in Navajo educational experiences through the twentieth century. She was the last Miss Indian BYU crowned in 2006. King is also a dedicated wife and mother to two toddlers. A version of the following will appear in a special issue on Miss Indian pageants, forthcoming in the Journal of the West .

The Tribe of Many Feathers (TMF), the BYU Native American student organization, hosted the Miss Indian BYU pageant for twenty-three consecutive years until 1990. TMF restarted the pageant in 2001. I was the last crowned Miss Indian BYU in 2006, since the TMF Council cancelled the pageant again in 2007. I had the opportunity to interview several former Miss Indian BYUs about their experiences as title-holders and pageant contestants including Vickie Sanders Bird and Jordan Zendejas who I feature in this blog post. The Miss Indian BYU Pageant and its winners’ memories reveal the ways that Native American LDS youth engaged and transformed material culture in the effort to represent BYU Indian students.

2006 Pageant. Farina is on the left.

Dr. Janice White Clemmer, a Wasco-Shawnee-Delaware and the first “American Indian woman in the United States to earn two masters degrees and two doctoral degrees,” worked with the BYU Native American Studies and Multicultural programs when TMF invited her to judge for Miss Indian BYU pageants during the 1980s. [1] According to her, the pageant “[celebrated] young American Indian womanhood.” [2] She elaborated on the criteria that the judges used to evaluate Miss Indian BYU contestants: “How does she look in her regalia? How does she carry herself? How fluent is she about her tribal knowledge? [Miss Indian BYU has] LDS standards and demonstrates best of both worlds, of all worlds . . . someone who represented her tribe, other tribes, school, and gospel.” [3] The Miss Indian BYU Pageant typically consisted of the following parts: presentation of traditional regalia, traditional talent, modern talent, and question and answer. The ability to wear and describe traditional clothing demonstrated knowledge of the contestant’s tribe and people. For example, I remember wearing a biil (Navajo rug dress), moccasins, and a squash blossom necklace for the first part of the pageant in 2006. I explained that the squash blossom once belonged to shinálí ‘asdzáníígíí (my grandmother). Shibízhí (my aunt) had made the necklace for her using the sand-casting technique. I wore the moccasins of a Yébíchai (Yei Bi Chei ceremonial) dancer. The clothing represented our people and cultures, and so the judges wanted to see how we (as contestants) would understand and convey the connections between how we appeared and what we emblematized–indigenous identity in a LDS school context.

Vickie Bird, Miss Indian BYU, 1972

As Miss Indian BYU in 1972, Vickie Bird Sanders (Mandan-Hidatsa) enjoyed meeting with different groups to share her culture and serve as an ambassador. She recalls, “When I was chosen, I felt like it was a very special calling to be able to represent the population of all of the Native Americans and represent BYU. I did a lot of speaking. I was going to Boy Scout clubs, going to schools, going to women’s clubs, and performing for General Authorities.” [4] During one of her visits to an elementary school, she frightened a little girl who closed her eyes tightly to avoid looking at her traditional regalia. Sanders explained to the girl that the rabbit fur hanging on her long hair was not alive, and then the girl became excited to touch the fur and hugged her. She remembered, “That’s when I realized that I wanted to keep doing that, I wanted to keep going to the elementary schools, meeting with the little children and having them give me hugs and wanting to touch my rabbit skin.” [5] Sanders later became a schoolteacher and continued to present at some public schools. In her presentations, she first appears to the children in “everyday modern” clothing and then changes into her traditional dress in front of them while describing the cultural meaning of each clothing piece. She prepares her presentations this way to show and complicate the meanings of “a real live Indian.” [6]

Sanders also explained that Janie Thompson, the director of Lamanite Generation (a BYU student performance group), designated

TMF Ladies and Float

her as a “spokesperson” because of her title. “I always had a part in the show where I could express thoughts about BYU and where we were at that time wherever we were performing,” she added. [7] Phillip Smith (Navajo), a member of TMF during her reign, remembered seeing Sanders speak publicly to students. She impressed the BYU community with her personal story of reprimanding some relatives for wearing BYU icons and clothing in disrespectful atmospheres such as bars and clubs where alcohol was distributed. After witnessing the bereft of her people and family due to alcoholism, Sanders beseeched students to reject alcohol completely. [8]

During her service as Miss Indian BYU, AIM activists especially criticized Sanders and told her, “[You’re] Apple Indians, you’re red on the outside but white on the inside and you’re not really an Indian.” Sanders remembered, “So many of them took pride in ‘why don’t you wear something that identifies you as native? Why don’t you wear a feather in your hair’” She responded, “That to me is not what needs to set me apart from who I am. I don’t need to grow my hair long or wear it in braids or wear a feather or wear my Indian dress to show people that I’m proud of who I am.” [9]

In the twenty-first century, Miss Indian BYU still sought to shape popular images and material culture of American Indians. Miss Indian BYU 2004-2005, Jordan Zendejas (Omaha), visited public schools in her formal mainstream attire to relate better to children. Zendejas recounted,

My year, my focus was on education and the youth, and so I would educate them about Native American people and how we are different tribes and how were different then and how we are now. I like to emphasize the now part, because some people believe I wear my regalia every day to school, so I even wore a pant suit one time and they were like that is not what you wear, and I was like “yeah it is” that was my main issue to many schools. [10]

Adult supervisors at some schools complained that she did not wear feathers in her hair, hold a tomahawk, or portray other such stereotypical images of Indians. She explained, “There would be people who think, ‘You’re not Indian enough. You don’t look Indian enough. Do you take being Indian seriously’” She continued, “I remember this one class, I walked in there and to my horror all the students were wearing fake leather and fringe and putting on war paint and feathers in their hair . . . [one] mom was like you don’t look Indian. “Neither does your son, but you dressed him up.” I didn’t say that, but in my head I wanted to.” She added, “I wasn’t necessarily wearing my regalia every time that I went to schools just to show them how we were just normal people now, we don’t wear regalia all the time. . . . I had my own agenda set out, and I guess the teachers had in their mind their agenda of what they wanted me to do, so when I didn’t do it they would get mad.” [11] Zendejas used such encounters to teach people that she was a contemporary Native American and not a relic of the American past and fantasy of “the frontier.” Zendejas attended BYU Law School, aspiring to follow her father’s footsteps as a lawyer. Refusing to appear in traditional regalia for her presentations, Zendejas wanted to show that American Indians were a changing and developing population like peoples throughout the world.

Like the little girl who was afraid of Vickie Sanders’s rabbit fur in her hair, Zendejas confronted misconceptions about American Indians through her attire and presentation. Zendejas, similar to Miss Indian BYUs decades ago, was determined to dismantle prejudices and worked to alter material images of Native Americans and LDS indigenous people in particular.

______

[1] Janice White Clemmer, “Native American Studies: A Utah Perspective,” Wicazo Sa Review 2, no. 2 (Autumn 1986): 18.

[2] Janice White Clemmer, interview by author, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 26, 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Victoria Bird Sanders, interview by Farina King, Provo, Utah, March 27, 2008, transcript, LDS Native American Oral History Collection, Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, Provo, Utah.

[5] Vickie Bird Sanders, interview by author, Provo, Utah, 24 March 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sanders, interview, 2008.

[8] Phillip Smith, interview by author, Monument Valley, Utah, August 10, 2013.

[9] Sanders, interview, 2008.

[10] Jordan Zendejas, interview by author, Provo, Utah, March 24, 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[11] Ibid.

By GuestSeptember 24, 2013

Almost exactly one year ago, the University of North Carolina Press published Edward Blum and Paul Harvey’s The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, a sweeping and provocative analysis of the ways in which Americans from various walks of life over the last four hundred (!) years have imagined Jesus. Among the many contributions the book makes, and of particular interest to JI readers, is the authors’ situating Mormons as important players in the larger story of race and religion they narrate so masterfully. In fact, one paragraph in particular has garnered more attention than nearly any other part of the book—a brief discussion in chapter 9 of the large, white marble Christus statue instantly recognizable to Mormons the world over. In the latest issue of the Journal of Mormon History, Noel Carmack authored a 21 page review of The Color of Christ, focusing on their treatment of Mormonism and paying particular attention to their discussion of the Christus. Professors Blum and Harvey generously accepted our invitation to respond here, as part of both our ongoing Responses series and as an appropriate contribution to our look at Mormon material culture this month.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 18, 2013

Laura Allred Hurtado contributes this next installment in the JI’s material culture month, on Mormon attempts to represent Jesus. Laura is the Global Acquisitions Curator for Art in the Church History Department. She has an MA in Art History and Visual Studies from the University of Utah and a BA in Art History and Curatorial Studies at BYU. Laura has presented papers at scholarly conferences and curated exhibits at the Utah Museum of Fine Art, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, and various other venues.

If my people, which are called by my name, shall humble themselves, and pray, and seek my face, and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin, and will heal their land.–2 Chronicles 7:14

All representations of divinity fail. Fail in that they are made of terrestrial materials, seen through non-celestial eyes.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 17, 2013

Tiffany T. Bowles offers this installment in the JI’s material culture month. Tiffany is a Curator of Education at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City. A native of Orem, Utah, she received a BA degree in history from BYU and an MA in Historical Administration from Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. She has worked for the National Park Service at Natchez National Historical Park in Natchez, Mississippi, and Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Illinois. In addition, she has worked at the Illinois State Military Museum and volunteered for the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

On a quiet fall day in October 1838, Amanda Barnes Smith and her family busily worked to prepare a campsite on the banks of Shoal Creek in the small community of Haun’s Mill, Missouri. After a grueling journey from Kirtland, Ohio, the Smiths were relieved at the prospect of settling near others of their Latter-day Saint faith on the unfamiliar frontier.

Without warning, the contentment of the autumn afternoon was broken by the sounds of a fast approaching mob. The men of the settlement gathered in a small blacksmith shop, prepared to defend themselves and their families. Amanda Smith and two of her children “escaped across the millpond on a slab-walk,” and sought safety in “some bottom land” near the creek [1]. When the firing ceased, Amanda returned to the blacksmith shop to find her husband and one of her sons among the 17 dead.

In Latter-day Saint memory, the brutality of the massacre at Haun’s Mill epitomizes decades of persecution endured by early members of the Church. Some Latter-day Saints today commemorate and try to make sense of this defining event in Church history by looking to the power of place and visiting the location of the massacre. A visit to this site today requires a long, bumpy drive on dirt and gravel roads (a hazardous journey after a rainstorm). The site of the massacre is an open field along a shallow creek bed. The only indication of the violent events that occurred at this location is a small sign detailing the events of October 30, 1838.

Others might look to the power of objects in making sense of the Haun’s Mill tragedy. Objects have the unique ability to provide a tangible connection to the past and allow us to transform “experience into substance” [2]. Steven Lubar and Kathleen Kenrick, Curators at the National Museum of American History, describe artifacts as “the touchstones that bring memories and meanings to life” [3]. Unfortunately, since the mill on Shoal Creek was torn down in 1845, tangible ties to Haun’s Mill are rare, though interest in objects related to the massacre has spanned two centuries.

In September 1888, Church historian Andrew Jenson and colleagues Edward Stevenson and Joseph S. Black embarked on a journey to visit Church history sites across the country. At Haun’s Mill, they noted a “remnant of the old mill dam,” including “five large pieces of timber left in the middle of the creek.” They mentioned standing “upon a solid ledge of rock,” where the milldam was originally located. The group then searched for the well where those murdered in the attack had been hastily buried. The site was marked “by an old millstone, formerly belonging to Jacob Haun’s mill” [4].

Latter-day Saint photographer George Edward Anderson mentioned another millstone when he visited Haun’s Mill in May 1907. He wrote of crossing the creek and finding “one of the old millstones, which we worked out of the ground and [then moved it] down to the edge of the creek and made two or three negatives of it, putting an inscription on one side” [5]. This particular stone was later moved to a city park in Breckenridge, Missouri [6].

Just two months after George Edward Anderson’s visit to Haun’s Mill, Latter-day Saint Charles White took a seven-day trip across the state of Missouri. Along the way, he gathered “relics” at each of the sites, hoping to establish a tangible connection not only to the various locations, but to the events that transpired there. At Haun’s Mill, White recorded that he waded out into Shoal Creek and broke several pieces off of an original millstone “as a relic of the blackest crime that was ever committed in our fair country” [7].

The interest in objects related to the Haun’s Mill Massacre continued into the late 20th century, when “Cowboy” Bill Howell, a resident of the area, discovered a piece of cast iron protruding from the bank of Shoal Creek. He assumed that he had found “the metal frame for half of the waterwheel from the old mill,” and “hoped that someday he might run upon the matching other half so he could reconstruct the wheel” [8]. In April 1986, Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion instructors Newell R. Kitchen and John L. Fowles asked Cowboy Bill if he would be interested in selling the metal wheel fragment to them, which he did for $25. Kitchen and Fowles later determined that the cast iron artifact was not a wheel frame, but was actually a “face wheel,” or a gear wheel that transferred power from the waterwheel to the rest of the mill’s machinery [9]. On August 11, 1986, the men delivered the face wheel to the LDS Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, where the artifact is now displayed as the lone representative of one of the most tragic events in Church history [10].

How can this rusty piece of cast iron connect us to the events of October 30, 1838? The basic function of this face wheel gives us insight into the type of work that was done at the mill on Shoal Creek. Face wheels of this kind were common in gristmills of the time period, and gristmills were used to grind grain into flour. The probability that the mill at the Haun’s Mill settlement was a gristmill is substantiated by a statement from Latter-day Saint Ellis Eamut who recorded that non-Mormon residents of the area were initially friendly with the Saints, using “[our] mill[s] for grinding” [11]. Interestingly, Eamut mentions that they also used the mill for ‘sawing,” indicating that the mill functioned as both a gristmill and a sawmill. A study of nineteenth century mills in South Carolina states that “a saw mill could often be found at the site of a grist mill. The two could be powered by the same wheel or turbine by using different gearing” [12].

In addition to increasing our understanding of the type of work done at the mill, the face wheel artifact can also connect us to the personal stories of Haun’s Mill. Latter-day Saint convert and successful millwright Jacob Myers from Richland County, Ohio, constructed the original mill on Shoal Creek in 1836. Myers later sold the mill to Jacob Haun, and Myers’ son, Jacob Myers Jr., helped Haun operate the mill. On the day of the 1838 attack at Haun’s Mill, Jacob Myers Jr. was shot through the leg as he attempted to run from the ill-fated blacksmith shop. One of the attackers approached him with a corn cutter, intending to kill him. According to Myers’ sister, “As [the attacker] raised his arm to strike, another one of the mob called out to him and told him if he touched my brother he would shoot him,” for Myers had “ground many a grist for him” [13]. Instead of killing him, the mob carried Myers to his home. His skill as a worker at the mill had saved his life.

The rusty face wheel on display at the Church History Museum serves as a tangible connection to the early Saints, increasing our understanding of their life and times and serving as a reminder of their sacrifices and courage. In a broader sense, this artifact also represents, as a plaque near the original millstone in Breckenridge, Missouri, states, “The perpetual need for greater understanding and tolerance between all peoples” [14].

Original cast iron face wheel from Haun’s Mill on display at the Church History Museum

George Edward Anderson 1907 photograph of original Haun’s Mill millstone, Courtesy Church Archives

______________________________________

[1] Journal of Amanda Barnes Smith, unpublished typescript, 3.

[2] Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 265.

[3] Steven Lubar and Kathleen Kenrick, “Looking at Artifacts, Thinking about History,” Smithsonian National Museum of American History “Guide to Doing History with Objects,” http://objectofhistory.org/guide/.

[4] “Half a Century Since,” Deseret News (October 3, 1888), 10. The “red millstone fragment” that marked the well was moved by area resident Glen E. Setzer in 1941. Setzer, unaware of the significance of the stone’s location, moved it to the site of a marker he constructed near the road (‘story of Haun’s Mill’ by the Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation, unpublished typescript, 2003, 5).

[5] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, T. Jeffrey Cottle, and Ted D. Stoddard, eds., Church History in Black and White: George Edward Anderson’s Photographic Mission to Latter-day Saint Historical Sites (Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 97, as quoted in Alexander L. Baugh, “The Haun’s Mill Stone at Breckenridge,” Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (Fall 2001), 211.

[6] Baugh, “The Haun’s Mill Stone at Breckenridge,” 211.

[7] Charles White, Charles White, Journal, 1907 [typescript] MSS SC 219, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, p. 13.

[8] Newell R. Kitchen and John L. Fowles, “Finding the Haun’s Mill Face Wheel,” Mormon Historical Studies 4, no. 2 (Fall 2003), 167.

[9] Kitchen and Fowles, “Finding the Haun’s Mill Face Wheel,” 170.

[10] Artifact acquisition records, artifact number LDS 87-26, Church History Museum.

[11] Ellis Eamut, “Reminiscence,” in Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 30 October 1838, 11.

[12] Chad O. Braley, Southeastern Archaeological Services, Inc., “Mills in the Upcountry: A Historic Context, and a Summary of a Mill Site on the Peters Creek Heritage Preserve, Spartanburg County, South Carolina,” unpublished manuscript prepared for the Spartanburg Water Authority, 2005, 12.

[13] Artemisia Sidnie Myers Foote, “Reminiscences, 1850-1899,” MSS SC 999, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[14] Historical marker at Breckenridge, Missouri City Park, dedicated May 26, 2000.

By GuestSeptember 13, 2013

Michael J. Altman received his Ph.D. in American Religious Cultures from Emory University and is an Instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama. Mike’s areas of interest are American religious history, theory and method in the study of religion, the history of comparative religion, and Asian religions in American culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript analyzing representations of Hinduism in nineteenth century America. This post originally appeared at Mike’s personal blog. He graciously allowed the Juvenile Instructor to repost it in its entirety.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

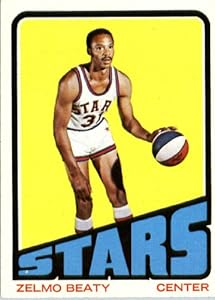

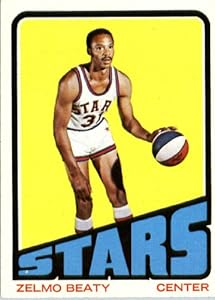

Every week host Josh Levin signs off with the phrase “remember Zelmo Beaty.” Beaty, a basketball star in the 60s and 70s passed away recently and this past week Hang Up and Listen reminded us why we should indeed remember him. Stefan Fatsis’ obituary of Beaty opened by staking out Beaty’s importance as a pioneer for black players in professional basketball. But what caught this religious historian’s attention was the confluence of race and religion that surrounded Beaty’s move to Salt Lake City to play for the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association in 1970.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 12, 2013

Justin Bray is an oral historian at the Church History Department in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is also an MA student at the University of Utah, where he studies American religious history. He has presented and published several papers on the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper among the Latter-day Saints.

I’ve always found objects meaningful tools to reconstruct the past.

When my great-grandfather passed away many years ago, my dad inherited an old baseball bat–probably because my brothers and I couldn’t stop watching The Sandlot, and throughout our childhood we collected an unhealthy number of baseball cards. I really didn’t know anything about my great-grandfather (at the time), let alone that he was a baseball player. But the more attention I paid to the bat, the more the bat became a kind of lens into my great-grandfather’s world.

Of course every baseball player has a bat, and at first glance baseball bats all look quite similar, but every nook and cranny spoke more about this specific player. For example, the most worn part of the bat’s handle was about an inch and a half above the knob, meaning he “choked up” on it considerably. From my background in baseball, I knew that players who choked up on the bat were generally shorter, faster, and “scrappier” players looking to just get on base, so that more powerful hitters could drive them home.

The kind wood the bat was made of, the fact that no pine tar was on it, and its length and weight continued to help piece together not only the kind of baseball player my great-grandfather may have been but also how far he played professionally and in what time period his career took place. A text, such as his obituary, may have said “he played baseball,” but studying a surviving object from is athletic career added elements to his narrative that evaded the written word.

This same approach can help historians study religion in America. Men, women, and children often use objects to express their faith, like a cross, phylactery, or CTR ring.

For some time now, I’ve looked at the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper as a way in which to study the devotional lives of the Latter-day Saints. When researching this sacred ritual, texts can only say so much: “The sacrament was administered today.” But when researching objects that were used to administer the sacrament, such as bread, water, wine, linens, cloths, plates, cups, trays, flagons, hats, gloves, and tables, the narrative expands.

Take the sacramental bread, for example. In nineteenth-century Utah, you didn’t just pick up a loaf of Wonder Bread on Saturday night, nor did you begin baking bread on Sunday morning. Preparing the sacramental emblems was a process that required at least daylong time and attention. It was often baked by sisters of the Relief Society and became a meaningful part of their devotional life.

Objects can open new channels of inquiry that words alone cannot. They can generate new questions to familiar narratives. But material culture also has its limits. Objects must be studied against texts to get good glimpse into religious worlds.

For those living in or near Salt Lake City, I’d like to give a plug for Kris Wright’s lecture tonight at the Assembly Hall on Temple Square. She’ll tell you better than I can how useful material culture is in studying the Latter-day Saints.

Newer Posts |

Older Posts

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

Recent Comments

Mark Staker on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “Jenny was always generous in sharing her knowledge. She was not only an exceptional educator (who also taught her colleagues along the way), but she…”

Gary Bergera on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “Jenny's great. Thanks for posting this.”

Kathy Cardon on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “I worked in the Church's Historical department when Jenny was in the Museum. I always enjoyed our interactions. Reading this article has been a real…”

Don Tate on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “Very well done and richly deserved! I am most proud of Jenny and how far she has come with her life, her scholarship, and her…”

Ben P on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “My favorite former boss and respected current historian!”

Hannah J on Legacies in Mormon Studies: “I really enjoyed this! Going to be thinking about playing the long game for a while. Thanks Amy and Jenny.”