By Farina KingOctober 11, 2013

John C. Begay recalled the day when his branch president, Don C. Hunsaker, pulled him out of his class at the Intermountain Indian Boarding School to invite him to attend the Latter-day Saint Indian Seminary program. His mother had enrolled him in seminary, but Begay followed his peers to the Catholic and Nazarene activities until Hunsaker found him. He then started to attend the seminary class of a respected LDS leader and local of Brigham City, Elder Boyd K. Packer. Begay claims, ??That?s where I was converted to the LDS Church. My mother had secretly signed me up for Seminary which became my favorite class?.?? [1].

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 26, 2013

This installment in the JI’s material culture month comes from Farina King of the Kinyaa’áanii (Towering House clan) of the Diné (Navajo). She is a second-year graduate student in the U.S. History Ph.D program at Arizona State University. She received her M.A. in African History from the University of Wisconsin and a B.A. from Brigham Young University with a double major in History and French Studies. King has written and presented about indigenous Mormon experiences in the twentieth century, drawing from interviews that she conducted for the LDS Native American Oral History Project at BYU. Her doctoral research traces the changes in Navajo educational experiences through the twentieth century. She was the last Miss Indian BYU crowned in 2006. King is also a dedicated wife and mother to two toddlers. A version of the following will appear in a special issue on Miss Indian pageants, forthcoming in the Journal of the West .

The Tribe of Many Feathers (TMF), the BYU Native American student organization, hosted the Miss Indian BYU pageant for twenty-three consecutive years until 1990. TMF restarted the pageant in 2001. I was the last crowned Miss Indian BYU in 2006, since the TMF Council cancelled the pageant again in 2007. I had the opportunity to interview several former Miss Indian BYUs about their experiences as title-holders and pageant contestants including Vickie Sanders Bird and Jordan Zendejas who I feature in this blog post. The Miss Indian BYU Pageant and its winners’ memories reveal the ways that Native American LDS youth engaged and transformed material culture in the effort to represent BYU Indian students.

2006 Pageant. Farina is on the left.

Dr. Janice White Clemmer, a Wasco-Shawnee-Delaware and the first “American Indian woman in the United States to earn two masters degrees and two doctoral degrees,” worked with the BYU Native American Studies and Multicultural programs when TMF invited her to judge for Miss Indian BYU pageants during the 1980s. [1] According to her, the pageant “[celebrated] young American Indian womanhood.” [2] She elaborated on the criteria that the judges used to evaluate Miss Indian BYU contestants: “How does she look in her regalia? How does she carry herself? How fluent is she about her tribal knowledge? [Miss Indian BYU has] LDS standards and demonstrates best of both worlds, of all worlds . . . someone who represented her tribe, other tribes, school, and gospel.” [3] The Miss Indian BYU Pageant typically consisted of the following parts: presentation of traditional regalia, traditional talent, modern talent, and question and answer. The ability to wear and describe traditional clothing demonstrated knowledge of the contestant’s tribe and people. For example, I remember wearing a biil (Navajo rug dress), moccasins, and a squash blossom necklace for the first part of the pageant in 2006. I explained that the squash blossom once belonged to shinálí ‘asdzáníígíí (my grandmother). Shibízhí (my aunt) had made the necklace for her using the sand-casting technique. I wore the moccasins of a Yébíchai (Yei Bi Chei ceremonial) dancer. The clothing represented our people and cultures, and so the judges wanted to see how we (as contestants) would understand and convey the connections between how we appeared and what we emblematized–indigenous identity in a LDS school context.

Vickie Bird, Miss Indian BYU, 1972

As Miss Indian BYU in 1972, Vickie Bird Sanders (Mandan-Hidatsa) enjoyed meeting with different groups to share her culture and serve as an ambassador. She recalls, “When I was chosen, I felt like it was a very special calling to be able to represent the population of all of the Native Americans and represent BYU. I did a lot of speaking. I was going to Boy Scout clubs, going to schools, going to women’s clubs, and performing for General Authorities.” [4] During one of her visits to an elementary school, she frightened a little girl who closed her eyes tightly to avoid looking at her traditional regalia. Sanders explained to the girl that the rabbit fur hanging on her long hair was not alive, and then the girl became excited to touch the fur and hugged her. She remembered, “That’s when I realized that I wanted to keep doing that, I wanted to keep going to the elementary schools, meeting with the little children and having them give me hugs and wanting to touch my rabbit skin.” [5] Sanders later became a schoolteacher and continued to present at some public schools. In her presentations, she first appears to the children in “everyday modern” clothing and then changes into her traditional dress in front of them while describing the cultural meaning of each clothing piece. She prepares her presentations this way to show and complicate the meanings of “a real live Indian.” [6]

Sanders also explained that Janie Thompson, the director of Lamanite Generation (a BYU student performance group), designated

TMF Ladies and Float

her as a “spokesperson” because of her title. “I always had a part in the show where I could express thoughts about BYU and where we were at that time wherever we were performing,” she added. [7] Phillip Smith (Navajo), a member of TMF during her reign, remembered seeing Sanders speak publicly to students. She impressed the BYU community with her personal story of reprimanding some relatives for wearing BYU icons and clothing in disrespectful atmospheres such as bars and clubs where alcohol was distributed. After witnessing the bereft of her people and family due to alcoholism, Sanders beseeched students to reject alcohol completely. [8]

During her service as Miss Indian BYU, AIM activists especially criticized Sanders and told her, “[You’re] Apple Indians, you’re red on the outside but white on the inside and you’re not really an Indian.” Sanders remembered, “So many of them took pride in ‘why don’t you wear something that identifies you as native? Why don’t you wear a feather in your hair’” She responded, “That to me is not what needs to set me apart from who I am. I don’t need to grow my hair long or wear it in braids or wear a feather or wear my Indian dress to show people that I’m proud of who I am.” [9]

In the twenty-first century, Miss Indian BYU still sought to shape popular images and material culture of American Indians. Miss Indian BYU 2004-2005, Jordan Zendejas (Omaha), visited public schools in her formal mainstream attire to relate better to children. Zendejas recounted,

My year, my focus was on education and the youth, and so I would educate them about Native American people and how we are different tribes and how were different then and how we are now. I like to emphasize the now part, because some people believe I wear my regalia every day to school, so I even wore a pant suit one time and they were like that is not what you wear, and I was like “yeah it is” that was my main issue to many schools. [10]

Adult supervisors at some schools complained that she did not wear feathers in her hair, hold a tomahawk, or portray other such stereotypical images of Indians. She explained, “There would be people who think, ‘You’re not Indian enough. You don’t look Indian enough. Do you take being Indian seriously’” She continued, “I remember this one class, I walked in there and to my horror all the students were wearing fake leather and fringe and putting on war paint and feathers in their hair . . . [one] mom was like you don’t look Indian. “Neither does your son, but you dressed him up.” I didn’t say that, but in my head I wanted to.” She added, “I wasn’t necessarily wearing my regalia every time that I went to schools just to show them how we were just normal people now, we don’t wear regalia all the time. . . . I had my own agenda set out, and I guess the teachers had in their mind their agenda of what they wanted me to do, so when I didn’t do it they would get mad.” [11] Zendejas used such encounters to teach people that she was a contemporary Native American and not a relic of the American past and fantasy of “the frontier.” Zendejas attended BYU Law School, aspiring to follow her father’s footsteps as a lawyer. Refusing to appear in traditional regalia for her presentations, Zendejas wanted to show that American Indians were a changing and developing population like peoples throughout the world.

Like the little girl who was afraid of Vickie Sanders’s rabbit fur in her hair, Zendejas confronted misconceptions about American Indians through her attire and presentation. Zendejas, similar to Miss Indian BYUs decades ago, was determined to dismantle prejudices and worked to alter material images of Native Americans and LDS indigenous people in particular.

______

[1] Janice White Clemmer, “Native American Studies: A Utah Perspective,” Wicazo Sa Review 2, no. 2 (Autumn 1986): 18.

[2] Janice White Clemmer, interview by author, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 26, 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Victoria Bird Sanders, interview by Farina King, Provo, Utah, March 27, 2008, transcript, LDS Native American Oral History Collection, Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, Provo, Utah.

[5] Vickie Bird Sanders, interview by author, Provo, Utah, 24 March 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sanders, interview, 2008.

[8] Phillip Smith, interview by author, Monument Valley, Utah, August 10, 2013.

[9] Sanders, interview, 2008.

[10] Jordan Zendejas, interview by author, Provo, Utah, March 24, 2007, recording in personal possession of author.

[11] Ibid.

By GuestSeptember 24, 2013

Almost exactly one year ago, the University of North Carolina Press published Edward Blum and Paul Harvey’s The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, a sweeping and provocative analysis of the ways in which Americans from various walks of life over the last four hundred (!) years have imagined Jesus. Among the many contributions the book makes, and of particular interest to JI readers, is the authors’ situating Mormons as important players in the larger story of race and religion they narrate so masterfully. In fact, one paragraph in particular has garnered more attention than nearly any other part of the book—a brief discussion in chapter 9 of the large, white marble Christus statue instantly recognizable to Mormons the world over. In the latest issue of the Journal of Mormon History, Noel Carmack authored a 21 page review of The Color of Christ, focusing on their treatment of Mormonism and paying particular attention to their discussion of the Christus. Professors Blum and Harvey generously accepted our invitation to respond here, as part of both our ongoing Responses series and as an appropriate contribution to our look at Mormon material culture this month.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 13, 2013

Michael J. Altman received his Ph.D. in American Religious Cultures from Emory University and is an Instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama. Mike’s areas of interest are American religious history, theory and method in the study of religion, the history of comparative religion, and Asian religions in American culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript analyzing representations of Hinduism in nineteenth century America. This post originally appeared at Mike’s personal blog. He graciously allowed the Juvenile Instructor to repost it in its entirety.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

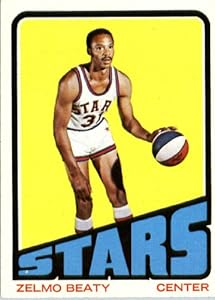

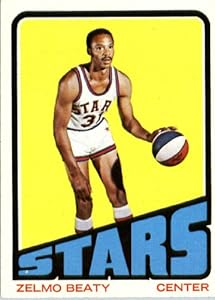

Every week host Josh Levin signs off with the phrase “remember Zelmo Beaty.” Beaty, a basketball star in the 60s and 70s passed away recently and this past week Hang Up and Listen reminded us why we should indeed remember him. Stefan Fatsis’ obituary of Beaty opened by staking out Beaty’s importance as a pioneer for black players in professional basketball. But what caught this religious historian’s attention was the confluence of race and religion that surrounded Beaty’s move to Salt Lake City to play for the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association in 1970.

Continue Reading

By David G.August 27, 2013

?Do you think President Kimball approves of your action?? This question, asked by an unnamed general authority of the soon-to-be excommunicated Elder George P. Lee of the First Quorum of the 70, captured the lingering tensions over the rapid decline of the ?Day of the Lamanite? that had marked Mormon views of Native Americans in the second half of the twentieth century. Lee, the first general authority of Native descent, was himself the product of several of the programs instituted under the direction of Apostle Spencer W. Kimball designed to educate American Indians and aid their acculturation into the dominant society. Even at the time of Lee?s call to the 70 in 1975, the church had begun reallocating resources away from the so-called ?Lamanite programs,? but the full implications of these decisions were not apparent until the mid-1980s. Lee responded to the question posed above by laying out a distinct interpretation of 3 Nephi 21:22-23, an interpretation that he argued Kimball had shared and that the General Authorities in the 1980s had abandoned. The 1980s, known as the decade when Church President Ezra Taft Benson challenged the Saints to increase and improve their devotional usage of the Book of Mormon?a challenge that saw marked results, at least as measured by the significant increase of citations to the work in General Conference talks?was also a decade of debate over the meaning of the book?s intended audience and purpose.[1]

Continue Reading

By CristineAugust 19, 2013

Mitt Romney?s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns came to seem, in the media frenzy of the last few years, like bookends to America?s much-touted Mormon moment. But Americans? fascination with the Latter-day Saints did not begin or end with Mitt Romney. This is not the first period in American history when non-Mormon Americans have, to some extent, embraced their LDS neighbors. In fact, Mitt Romney isn?t even the first Republican Romney whose religious affiliation has colored his national political image. His father George, the successful head of the American Motor Company in the 1950s and popular governor of Michigan in the 1960s, was a prominent candidate for the 1968 Republican nomination for President. Also like Mitt, George owed at least some measure of his political success to a period of increased interest in and positive feeling towards the Mormons. As J.B. Haws, Assistant Professor of Church History at BYU, shows in his article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Mormon History, George Romney?s candidacy was not seen as tainted by a ?Mormon problem,? as were his son?s campaigns a half-century later. [1] In the United States in the 1960s, the Romneys? Mormonism simply ?mattered less? than it does in the 21st century. And if it mattered at all, Haws argues, it did so by lending George Romney the air of ?benign wholesomeness? that characterized public perceptions of the Latter-day Saints in this period (99).

Haws? current article is based on the research for his forthcoming book The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (OUP, November 2013), and essentially lays the groundwork for that longer study, in which he traces public perceptions of Mormonism in the American media across the last half-century. In the 1960s, he argues, George Romney ran for the Republican nomination for the presidency and faced remarkably few challenges to his religion?or at least what look like remarkably few challenges to those of us who lived through the most recent Mormon moment. By comparing political polling data from both Romneys? campaigns and examining news coverage of the elder Romney?s presidential aspirations and editorial commentary on his campaign and on the larger question of the role a candidate?s religion should play in voters? assessment of his fitness for office, Haws convincingly demonstrates that Americans were less concerned in the 1960s?or at least said they were less concerned?by the possibility of having a Mormon in the White House than were their early 21st-century counterparts. While George Romney?s religion was occasionally challenged?primarily, Haws claims, regarding the Church?s policies on race (remember, George Romney was running for the presidency in the midst of the Civil Rights movements, and a decade before the Church lifted its ban on blacks in the priesthood)?according to Haws it was not Romney?s religion but his moderate politics and his ill-advised declaration in 1967 that he had been ?brainwashed? into supporting the Vietnam war that sunk him with American voters. In short, Haws argues that political views, not religious beliefs, were the elder Romney?s greatest obstacles.

Continue Reading

By Nate R.July 12, 2013

This is the second in a three-part series of posts about Joseph F. Smith?s experiences during the New York Draft Riots of July 1863. See the first part here.

Image: CHARGE OF THE POLICE ON THE RIOTERS AT THE “TRIBUNE” OFFICE, Harper?s Weekly, August 1, 1863, p. 484 [1]

Joseph F. Smith arrived in New York City on July 6, 1863, after an unremarkable journey from Liverpool (though he did mention with disappointment on July 4th that ?no demonstrations were mad[e] to commemorate the aneversery of American Independence,?[2] ). He had been recently released from his missionary duties in the British Isles Mission, and was fulfilling an assignment to see several groups of Mormon emigrants safely into the U.S. and on their way toward Utah.

Continue Reading

By GuestJune 14, 2013

Please join us in welcoming this guest post from Edward Blum, a recognized scholar of race and religion in U.S. history who has contributed to JI previously. Ed is associate professor of history at San Diego State University. He is the author of Reforging the White Republic: Race, Religion, and American Nationalism, 1865-1898 (2005), W. E. B. Du Bois, American Prophet (2007), and most recently, co-author (with Paul Harvey) of The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America (2012). He is the co-editor (with Paul Harvey) of The Columbia Guide to Religion in American History (2012), (with Jason R. Young) The Souls of W. E. B. Du Bois: New Essays and Reflections (2009), and (with W. Scott Poole) Vale of Tears: New Essays on Religion and Reconstruction (2005). Ed also blogs at Religion in American History and Teaching United States History, and last week attended his very first Mormon History Association conference in Layton, Utah.

___________________________

Has darkness ever overwhelmed you? Have you seen cities sink and communities set ablaze? Has a voice saved you? If you know the Book of Mormon, then you are familiar with the tale I tell. After hundreds of pages chronicling the ebbs and flows of civilizations, the narrative reaches a climax. In Palestine, Jesus Christ was crucified and buried. The world felt the reverberations. “Thick darkness” fell upon the land. Nothing could bring light, “neither candles, neither torches; neither could there be fire kindled with their fine and exceeding dry wood, so that there could not be any light at all.” The sounds of howling and weeping pieced the darkness. Sadness reigned.

It is difficult to overstate the drama and the beauty of the Book of Mormon’s rendering of these days. As one who watched silvery strands cloud the corneas of my infant son and darken his vision onto blindness, as one who takes the Christ story seriously in the depth of my soul, and as one who more and more considers the place of the sun and the moon, the land and the sea, in our religious imaginations, this scripture leaves me in tears. It also leaves me spinning about why the Book of Mormon is vital for American religious historians. It is not simply an artifact. It is also a treasure trove of ideas. To me, it should be required reading for anyone in my guild, and here are a few reasons.

First, the contents and the context feed one another. Most of us teach the context of Mormonism’s emergence. We teach about the second great awakening and the burned-over district, the dramatic tale of young Joseph Smith visited by God the Father, Jesus the Son, and Moroni the angel, and the complex and conflicted translating process. The content dramatizes the context and vice versa. When Joseph Smith translated the tale of the world going dark, he was sitting in darkness. When Smith described the various plates that had different forms of history written upon them, Smith was working from plates that held sacred histories at the same time George Bancroft was writing from paper on paper alternative histories of America. I am not suggesting that the context determined the content, not one bit. Rather, the drama of Smith’s translation seems heightened when we take seriously the text which he translated.

Second, the “wrapping” of the Book of Mormon can be stunningly interesting. There was not one Book of Mormon, but several even from the beginning. As Laurie Maffly-Kipp notes in her introduction to the Penguin edition, slight changes from the 1830 to the 1840 edition were crucial. The 1830 version used the word “white” to refer to the Lamanites. The 1840 version used “pure.” It was the 1830 version that became “the” wording for more than a century. Just as the distinction between “light” and “white” is crucial when we think of how Smith’s first vision is textually rendered versus how it is visually displayed, the difference between “white” and “pure” has been crucial too. Following the 1978 declaration to end the priesthood ban on black men, the 1981 edition inserted “pure.”

There have been other meaningful modifications as well, and not all textual. We know of the new subtitle, “Another Testament of Jesus Christ,” but there was also the inclusion of imagery. The Book of Mormon I grabbed from a hotel in 2007, which was my first introduction to the book, has eight images after an introduction and the testimonies. Heinrich Hofmann’s “The Lord Jesus Christ” looks slightly down and to our right, perhaps directing with his eyes to turn the page. (interestingly enough, it is a Hofmann painting of Jesus that “frames” Thomas S. Monson’s online biography, an image he claims to have had since the 1950s). On the next page of this Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith looks to the left, as if back at Jesus. Then there is Lehi, Alma, Samuel the Lamanite, and finally John Scott’s “Jesus Christ visits the Americas” and Tom Lovell’s “Moroni buries the Nephite record.” Bulging biceps and earnest prayer mark these paintings. The images frame the text, providing readers a narrative before the narrative. A visual arc precedes the textual arc. What is not there is fascinating too. There is no “first vision” so God the Father is not viewed in human form. Reading these images offer another layer of reading the Book of Mormon.

Finally, the arguments against reading the Book(s) of Mormon seem weak to me. It may be the case, as Terryl Givens has argued, that few Americans read the Book of Mormon in the nineteenth century. But that is true of lots of books and other texts. How many fugitive slave narratives went unread? Emily Dickinson’s poetry was kept private. Moreover, some pretty important Americans did read the book, including Brigham Young.

It is too easy to quote Mark Twain to explain away the book. To be blunt, there is a lot of nineteenth-century writing that felt like “chloroform in print.” Most of my students dislike Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin because it is too long and too detailed. Moby-Dick is so full of symbol, symbols, and symbolism that it often feels like the whale itself: too massive to comprehend. Readers can just as easily get lost searching for the white whale as they are following the Nephites, Lamanites, Jaredites, and all the other “ites.”

What I love about the Book of Mormon is that Smith and the writers were willing to tarry where Moby-Dick’s “Ishmael” was not. Near the beginning of Melville’s work, the one we can call “Ishmael” stumbles into a “Negro” church. There, he hears a sermon about “the darkness of blackness, and the weeping and wailing and teeth-gnashing.” Ishmael “backed out.” To him, it was a “trap.”

When we read the Book of Mormon, we willingly enter the “trap.” The darkness descends; the world weeps. But then a voice calls; a body appears; we touch it and listen to his teachings. Then, we are told to sing. Perhaps Mark Twain’s boredom (and ours) tells us a lot more about his (and our) sacred (in)sensitivities and less about Smith or the Book of Mormon.

By Ben PApril 17, 2013

Desperate times (the expected dearth of posts at the end of the semester) call for desperate measures (narcissistically posting about our own scholarship).

Parley Pratt, whose theology was as rugged as his looks.

In summer 2009, I participated in the Mormon Scholars Summer Seminar, that year led by Terryl Givens and Matt Grow, where I had the opportunity to study the writings of the Pratt brothers. While my seminar paper was on Parley Pratt’s theology of embodiment, which soon evolved into a larger article on early Mormon theologies of embodiment in general, the topic with which I became particularly transfixed was how Joseph Smith’s teachings were adapted and appropriated during the first few years after his death. At first, I was interested in the very parochial nature of the issue—the specifics of theological development, who said what and when, and what ideas were forgotten, emphasized, or even created anew. But I then became even more interested in broader questions: how were Smith’s ideas interpreted in the first place within a specific cultural environment, and how did Smith’s successors utilize that environment when molding their own theology? And further, what does that process tell us about the development of religious traditions in general, and the progression of religion in antebellum America in particular?

Continue Reading

By MaxFebruary 26, 2013

Note: It is a pleasure to have Margaret Blair Young contribute to JI’s monthlong series on issues of Race and Mormonism. Margaret Blair Young has written extensively on Blacks in the western USA and particilarly Black Latter-day Saints. Much of her work has been co-authored with Darius Gray. She authored I Am Jane.

The first staged reading of I Am Jane was on the Nelke theater stage at BYU. It was the climax of a playwriting class, and met some deserved criticism. It was, as I recall, about 120 pages. Too many words. The first draft I wrote used a clichéd convention: rebellious teenager dreams about/ learns about/ re-enacts the life of a heroic ancestor and gains self-respect and courage. But such a play is more about the teen than the character whose life I wanted to explore. And I was researching it even as I was scripting the play.

After I had chiseled away at the script, I thought it ready for its debut, which happened on March 5th, 2000. The play was that month?s Genesis meeting. There was no stage, so we threw a blanket over a trellis to suggest a covered wagon, used the sacrament table for Jane?s death bed, and the clerk?s table for other scenes.

I knew there was more sculpting to do, and revised several times before our performances in Springville?s Villa Theater. During that two-week run, I played Lucy Mack Smith, who let Jane handle a bundle purportedly containing the Urim and Thummin. (This is according to Jane?s life story, which she dictated near the end of her life.)

Continue Reading

Newer Posts |

Older Posts

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

Recent Comments

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “Interesting, Jack. But just to reiterate, I think JS saw the SUPPRESSION of Platonic ideas as creating the loss of truth and not the addition.…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “Thanks for your insights--you've really got me thinking. I can't get away from the notion that the formation of the Great and Abominable church was an…”

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “In the intro to DC 76 in JS's 1838 history, JS said, "From sundry revelations which had been received, it was apparent that many important…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “"I’ve argued that God’s corporality isn’t that clear in the NT, so it seems to me that asserting that claims of God’s immateriality happened AFTER…”

Steve Fleming on Study and Faith, 5:: “The burden of proof is on the claim of there BEING Nephites. From a scholarly point of view, the burden of proof is on the…”

Eric on Study and Faith, 5:: “But that's not what I was saying about the nature of evidence of an unknown civilization. I am talking about linguistics, not ruins. …”