By GuestSeptember 17, 2013

Tiffany T. Bowles offers this installment in the JI’s material culture month. Tiffany is a Curator of Education at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City. A native of Orem, Utah, she received a BA degree in history from BYU and an MA in Historical Administration from Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. She has worked for the National Park Service at Natchez National Historical Park in Natchez, Mississippi, and Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Illinois. In addition, she has worked at the Illinois State Military Museum and volunteered for the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

On a quiet fall day in October 1838, Amanda Barnes Smith and her family busily worked to prepare a campsite on the banks of Shoal Creek in the small community of Haun’s Mill, Missouri. After a grueling journey from Kirtland, Ohio, the Smiths were relieved at the prospect of settling near others of their Latter-day Saint faith on the unfamiliar frontier.

Without warning, the contentment of the autumn afternoon was broken by the sounds of a fast approaching mob. The men of the settlement gathered in a small blacksmith shop, prepared to defend themselves and their families. Amanda Smith and two of her children “escaped across the millpond on a slab-walk,” and sought safety in “some bottom land” near the creek [1]. When the firing ceased, Amanda returned to the blacksmith shop to find her husband and one of her sons among the 17 dead.

In Latter-day Saint memory, the brutality of the massacre at Haun’s Mill epitomizes decades of persecution endured by early members of the Church. Some Latter-day Saints today commemorate and try to make sense of this defining event in Church history by looking to the power of place and visiting the location of the massacre. A visit to this site today requires a long, bumpy drive on dirt and gravel roads (a hazardous journey after a rainstorm). The site of the massacre is an open field along a shallow creek bed. The only indication of the violent events that occurred at this location is a small sign detailing the events of October 30, 1838.

Others might look to the power of objects in making sense of the Haun’s Mill tragedy. Objects have the unique ability to provide a tangible connection to the past and allow us to transform “experience into substance” [2]. Steven Lubar and Kathleen Kenrick, Curators at the National Museum of American History, describe artifacts as “the touchstones that bring memories and meanings to life” [3]. Unfortunately, since the mill on Shoal Creek was torn down in 1845, tangible ties to Haun’s Mill are rare, though interest in objects related to the massacre has spanned two centuries.

In September 1888, Church historian Andrew Jenson and colleagues Edward Stevenson and Joseph S. Black embarked on a journey to visit Church history sites across the country. At Haun’s Mill, they noted a “remnant of the old mill dam,” including “five large pieces of timber left in the middle of the creek.” They mentioned standing “upon a solid ledge of rock,” where the milldam was originally located. The group then searched for the well where those murdered in the attack had been hastily buried. The site was marked “by an old millstone, formerly belonging to Jacob Haun’s mill” [4].

Latter-day Saint photographer George Edward Anderson mentioned another millstone when he visited Haun’s Mill in May 1907. He wrote of crossing the creek and finding “one of the old millstones, which we worked out of the ground and [then moved it] down to the edge of the creek and made two or three negatives of it, putting an inscription on one side” [5]. This particular stone was later moved to a city park in Breckenridge, Missouri [6].

Just two months after George Edward Anderson’s visit to Haun’s Mill, Latter-day Saint Charles White took a seven-day trip across the state of Missouri. Along the way, he gathered “relics” at each of the sites, hoping to establish a tangible connection not only to the various locations, but to the events that transpired there. At Haun’s Mill, White recorded that he waded out into Shoal Creek and broke several pieces off of an original millstone “as a relic of the blackest crime that was ever committed in our fair country” [7].

The interest in objects related to the Haun’s Mill Massacre continued into the late 20th century, when “Cowboy” Bill Howell, a resident of the area, discovered a piece of cast iron protruding from the bank of Shoal Creek. He assumed that he had found “the metal frame for half of the waterwheel from the old mill,” and “hoped that someday he might run upon the matching other half so he could reconstruct the wheel” [8]. In April 1986, Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion instructors Newell R. Kitchen and John L. Fowles asked Cowboy Bill if he would be interested in selling the metal wheel fragment to them, which he did for $25. Kitchen and Fowles later determined that the cast iron artifact was not a wheel frame, but was actually a “face wheel,” or a gear wheel that transferred power from the waterwheel to the rest of the mill’s machinery [9]. On August 11, 1986, the men delivered the face wheel to the LDS Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, where the artifact is now displayed as the lone representative of one of the most tragic events in Church history [10].

How can this rusty piece of cast iron connect us to the events of October 30, 1838? The basic function of this face wheel gives us insight into the type of work that was done at the mill on Shoal Creek. Face wheels of this kind were common in gristmills of the time period, and gristmills were used to grind grain into flour. The probability that the mill at the Haun’s Mill settlement was a gristmill is substantiated by a statement from Latter-day Saint Ellis Eamut who recorded that non-Mormon residents of the area were initially friendly with the Saints, using “[our] mill[s] for grinding” [11]. Interestingly, Eamut mentions that they also used the mill for ‘sawing,” indicating that the mill functioned as both a gristmill and a sawmill. A study of nineteenth century mills in South Carolina states that “a saw mill could often be found at the site of a grist mill. The two could be powered by the same wheel or turbine by using different gearing” [12].

In addition to increasing our understanding of the type of work done at the mill, the face wheel artifact can also connect us to the personal stories of Haun’s Mill. Latter-day Saint convert and successful millwright Jacob Myers from Richland County, Ohio, constructed the original mill on Shoal Creek in 1836. Myers later sold the mill to Jacob Haun, and Myers’ son, Jacob Myers Jr., helped Haun operate the mill. On the day of the 1838 attack at Haun’s Mill, Jacob Myers Jr. was shot through the leg as he attempted to run from the ill-fated blacksmith shop. One of the attackers approached him with a corn cutter, intending to kill him. According to Myers’ sister, “As [the attacker] raised his arm to strike, another one of the mob called out to him and told him if he touched my brother he would shoot him,” for Myers had “ground many a grist for him” [13]. Instead of killing him, the mob carried Myers to his home. His skill as a worker at the mill had saved his life.

The rusty face wheel on display at the Church History Museum serves as a tangible connection to the early Saints, increasing our understanding of their life and times and serving as a reminder of their sacrifices and courage. In a broader sense, this artifact also represents, as a plaque near the original millstone in Breckenridge, Missouri, states, “The perpetual need for greater understanding and tolerance between all peoples” [14].

Original cast iron face wheel from Haun’s Mill on display at the Church History Museum

George Edward Anderson 1907 photograph of original Haun’s Mill millstone, Courtesy Church Archives

______________________________________

[1] Journal of Amanda Barnes Smith, unpublished typescript, 3.

[2] Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 265.

[3] Steven Lubar and Kathleen Kenrick, “Looking at Artifacts, Thinking about History,” Smithsonian National Museum of American History “Guide to Doing History with Objects,” http://objectofhistory.org/guide/.

[4] “Half a Century Since,” Deseret News (October 3, 1888), 10. The “red millstone fragment” that marked the well was moved by area resident Glen E. Setzer in 1941. Setzer, unaware of the significance of the stone’s location, moved it to the site of a marker he constructed near the road (‘story of Haun’s Mill’ by the Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation, unpublished typescript, 2003, 5).

[5] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, T. Jeffrey Cottle, and Ted D. Stoddard, eds., Church History in Black and White: George Edward Anderson’s Photographic Mission to Latter-day Saint Historical Sites (Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 97, as quoted in Alexander L. Baugh, “The Haun’s Mill Stone at Breckenridge,” Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (Fall 2001), 211.

[6] Baugh, “The Haun’s Mill Stone at Breckenridge,” 211.

[7] Charles White, Charles White, Journal, 1907 [typescript] MSS SC 219, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, p. 13.

[8] Newell R. Kitchen and John L. Fowles, “Finding the Haun’s Mill Face Wheel,” Mormon Historical Studies 4, no. 2 (Fall 2003), 167.

[9] Kitchen and Fowles, “Finding the Haun’s Mill Face Wheel,” 170.

[10] Artifact acquisition records, artifact number LDS 87-26, Church History Museum.

[11] Ellis Eamut, “Reminiscence,” in Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 30 October 1838, 11.

[12] Chad O. Braley, Southeastern Archaeological Services, Inc., “Mills in the Upcountry: A Historic Context, and a Summary of a Mill Site on the Peters Creek Heritage Preserve, Spartanburg County, South Carolina,” unpublished manuscript prepared for the Spartanburg Water Authority, 2005, 12.

[13] Artemisia Sidnie Myers Foote, “Reminiscences, 1850-1899,” MSS SC 999, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[14] Historical marker at Breckenridge, Missouri City Park, dedicated May 26, 2000.

By GuestSeptember 13, 2013

Michael J. Altman received his Ph.D. in American Religious Cultures from Emory University and is an Instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama. Mike’s areas of interest are American religious history, theory and method in the study of religion, the history of comparative religion, and Asian religions in American culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript analyzing representations of Hinduism in nineteenth century America. This post originally appeared at Mike’s personal blog. He graciously allowed the Juvenile Instructor to repost it in its entirety.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

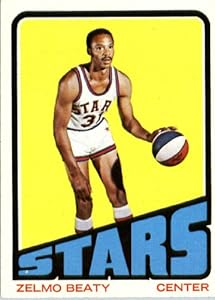

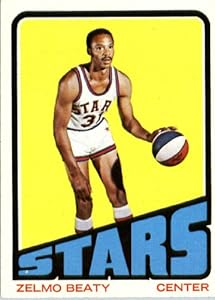

Every week host Josh Levin signs off with the phrase “remember Zelmo Beaty.” Beaty, a basketball star in the 60s and 70s passed away recently and this past week Hang Up and Listen reminded us why we should indeed remember him. Stefan Fatsis’ obituary of Beaty opened by staking out Beaty’s importance as a pioneer for black players in professional basketball. But what caught this religious historian’s attention was the confluence of race and religion that surrounded Beaty’s move to Salt Lake City to play for the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association in 1970.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 12, 2013

Justin Bray is an oral historian at the Church History Department in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is also an MA student at the University of Utah, where he studies American religious history. He has presented and published several papers on the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper among the Latter-day Saints.

I’ve always found objects meaningful tools to reconstruct the past.

When my great-grandfather passed away many years ago, my dad inherited an old baseball bat–probably because my brothers and I couldn’t stop watching The Sandlot, and throughout our childhood we collected an unhealthy number of baseball cards. I really didn’t know anything about my great-grandfather (at the time), let alone that he was a baseball player. But the more attention I paid to the bat, the more the bat became a kind of lens into my great-grandfather’s world.

Of course every baseball player has a bat, and at first glance baseball bats all look quite similar, but every nook and cranny spoke more about this specific player. For example, the most worn part of the bat’s handle was about an inch and a half above the knob, meaning he “choked up” on it considerably. From my background in baseball, I knew that players who choked up on the bat were generally shorter, faster, and “scrappier” players looking to just get on base, so that more powerful hitters could drive them home.

The kind wood the bat was made of, the fact that no pine tar was on it, and its length and weight continued to help piece together not only the kind of baseball player my great-grandfather may have been but also how far he played professionally and in what time period his career took place. A text, such as his obituary, may have said “he played baseball,” but studying a surviving object from is athletic career added elements to his narrative that evaded the written word.

This same approach can help historians study religion in America. Men, women, and children often use objects to express their faith, like a cross, phylactery, or CTR ring.

For some time now, I’ve looked at the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper as a way in which to study the devotional lives of the Latter-day Saints. When researching this sacred ritual, texts can only say so much: “The sacrament was administered today.” But when researching objects that were used to administer the sacrament, such as bread, water, wine, linens, cloths, plates, cups, trays, flagons, hats, gloves, and tables, the narrative expands.

Take the sacramental bread, for example. In nineteenth-century Utah, you didn’t just pick up a loaf of Wonder Bread on Saturday night, nor did you begin baking bread on Sunday morning. Preparing the sacramental emblems was a process that required at least daylong time and attention. It was often baked by sisters of the Relief Society and became a meaningful part of their devotional life.

Objects can open new channels of inquiry that words alone cannot. They can generate new questions to familiar narratives. But material culture also has its limits. Objects must be studied against texts to get good glimpse into religious worlds.

For those living in or near Salt Lake City, I’d like to give a plug for Kris Wright’s lecture tonight at the Assembly Hall on Temple Square. She’ll tell you better than I can how useful material culture is in studying the Latter-day Saints.

By David G.August 27, 2013

?Do you think President Kimball approves of your action?? This question, asked by an unnamed general authority of the soon-to-be excommunicated Elder George P. Lee of the First Quorum of the 70, captured the lingering tensions over the rapid decline of the ?Day of the Lamanite? that had marked Mormon views of Native Americans in the second half of the twentieth century. Lee, the first general authority of Native descent, was himself the product of several of the programs instituted under the direction of Apostle Spencer W. Kimball designed to educate American Indians and aid their acculturation into the dominant society. Even at the time of Lee?s call to the 70 in 1975, the church had begun reallocating resources away from the so-called ?Lamanite programs,? but the full implications of these decisions were not apparent until the mid-1980s. Lee responded to the question posed above by laying out a distinct interpretation of 3 Nephi 21:22-23, an interpretation that he argued Kimball had shared and that the General Authorities in the 1980s had abandoned. The 1980s, known as the decade when Church President Ezra Taft Benson challenged the Saints to increase and improve their devotional usage of the Book of Mormon?a challenge that saw marked results, at least as measured by the significant increase of citations to the work in General Conference talks?was also a decade of debate over the meaning of the book?s intended audience and purpose.[1]

Continue Reading

By CristineAugust 19, 2013

Mitt Romney?s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns came to seem, in the media frenzy of the last few years, like bookends to America?s much-touted Mormon moment. But Americans? fascination with the Latter-day Saints did not begin or end with Mitt Romney. This is not the first period in American history when non-Mormon Americans have, to some extent, embraced their LDS neighbors. In fact, Mitt Romney isn?t even the first Republican Romney whose religious affiliation has colored his national political image. His father George, the successful head of the American Motor Company in the 1950s and popular governor of Michigan in the 1960s, was a prominent candidate for the 1968 Republican nomination for President. Also like Mitt, George owed at least some measure of his political success to a period of increased interest in and positive feeling towards the Mormons. As J.B. Haws, Assistant Professor of Church History at BYU, shows in his article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Mormon History, George Romney?s candidacy was not seen as tainted by a ?Mormon problem,? as were his son?s campaigns a half-century later. [1] In the United States in the 1960s, the Romneys? Mormonism simply ?mattered less? than it does in the 21st century. And if it mattered at all, Haws argues, it did so by lending George Romney the air of ?benign wholesomeness? that characterized public perceptions of the Latter-day Saints in this period (99).

Haws? current article is based on the research for his forthcoming book The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (OUP, November 2013), and essentially lays the groundwork for that longer study, in which he traces public perceptions of Mormonism in the American media across the last half-century. In the 1960s, he argues, George Romney ran for the Republican nomination for the presidency and faced remarkably few challenges to his religion?or at least what look like remarkably few challenges to those of us who lived through the most recent Mormon moment. By comparing political polling data from both Romneys? campaigns and examining news coverage of the elder Romney?s presidential aspirations and editorial commentary on his campaign and on the larger question of the role a candidate?s religion should play in voters? assessment of his fitness for office, Haws convincingly demonstrates that Americans were less concerned in the 1960s?or at least said they were less concerned?by the possibility of having a Mormon in the White House than were their early 21st-century counterparts. While George Romney?s religion was occasionally challenged?primarily, Haws claims, regarding the Church?s policies on race (remember, George Romney was running for the presidency in the midst of the Civil Rights movements, and a decade before the Church lifted its ban on blacks in the priesthood)?according to Haws it was not Romney?s religion but his moderate politics and his ill-advised declaration in 1967 that he had been ?brainwashed? into supporting the Vietnam war that sunk him with American voters. In short, Haws argues that political views, not religious beliefs, were the elder Romney?s greatest obstacles.

Continue Reading

By GuestAugust 14, 2013

This post continues the JI’s occasional “Responses” series and contributes to the August theme of 20th Century Mormonism. Semi-regular guest and friend of the JI Patrick Mason, Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies at Claremont, contributes this installment.

Review of David Pulsipher, “Prepared to Abide the Penalty’: Latter-day Saints and Civil Disobedience,” JMH 39:3 (Summer 2013): 131-162.

Pop quiz: Which group maintained the longest civil disobedience movement in American history, and the first such movement not to descend into violence? Since you’re reading a Mormon history blog, the question is a bit like asking who’s buried in Grant’s tomb. Yet even with the prodigious output of scholars working on Mormon related topics in recent years, there are relatively few offerings that not only give us new details but also really help us see Mormonism through a new perspective. David Pulsipher’s recent JMH article is one of those.

I should reveal my biases up front: David is a good friend, and the two of us are (slowly) working together on a book-length treatment of a Mormon theological ethic of peace. So I’m naturally inclined to say nice things about him and his work. This post will be no exception. The basic historical trajectory of Pulsipher’s article, covering the twenty-eight years from the first federal anti-polygamy legislation until the Manifesto, doesn’t cover any particularly new ground for students of Mormon history. It’s what Pulsipher does in covering that ground that is innovative. In a subfield that is always striving for relevance to broader themes and narratives, Pulsipher shows persuasively that Mormon polygamists (mostly the male priesthood leadership) anticipated many of the strategies that would be employed in the twentieth century by nonviolent civil disobedience movements led by Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. The Mormon case demonstrates how nonviolent social movements can “emerge from unexpected quarters” (134). More significantly, I think, the article shows how Mormon history profits from engagement with political theory–plenty of John Rawls here, in easily digestible form–and that Mormonism can contribute to and substantially nuance established political theory.

Pulsipher begins with definitions. The Latter-day Saints’ nineteenth-century civil disobedience, like that of later theorists and practitioners, had three key characteristics: “(1) a fundamental distinction between just and unjust laws, (2) a conscientious, public, and nonviolent breach of an unjust law, seeking to change that law either through moral suasion or by frustrating its enforcement, and (3) fidelity to the rule of law generally, demonstrated by a willingness to obey just laws and to submit to the legal penalties for disobeying unjust laws” (138).

A typically telling illustration of the Mormons’ approach is offered by John Taylor, who relates being brought into court to give evidence in a polygamy trial: “I was asked if I believed in keeping the laws of the United States. I answered Yes, I believe in keeping them all but one. What one is that? It is that one in relation to plurality of wives. Why don’t you believe in keeping that? Because I believe it is at variance with the genius and spirit of our institutions–it is a violation of the Constitution of the United States, and it is contrary to the law of God.” Taylor then said that he was “prepared to abide the penalty” of taking such a stance. (144)

Pulsipher also traces the Latter-day Saints’ twentieth-century retreat from the civil disobedience and in some ways their own history. He offers several compelling reasons for why the heritage of civil disobedience didn’t take hold in twentieth-century LDS culture: its failure to achieve its explicit purpose (to preserve plural marriage); the wide unpopularity of that proximate purpose, increasingly among the Saints themselves; Mormons’ shift to emphasize loyalty to the nation and their excellence in Victorian moral virtues; the continued use of the rhetoric and strategies of civil disobedience by Fundamentalist LDS groups; and the church leadership’s conservative reaction to the “disrespect for law and order” characteristic of the late 1960s.

But not all is lost: Pulsipher intriguingly provides an extended quote from a 2009 speech at BYU-Idaho in which Elder Dallin H. Oaks glowingly approved of a “national anti-government movement” led by a Mongolian woman (161). The lesson here is that Mormons are just like other Americans–we like civil disobedience, especially in retrospect, when it achieves goals we deem worthy, and castigate it as unpatriotic and dangerous when applied toward goals we don’t share.

I take minor exception to one small point made in the article. Pulsipher demonstrates persuasively how the Latter-day Saints relied upon biblical, not American, precedents in justifying their civil disobedience–Daniel, not Thoreau, was their archetype. Their remarkable persistence in the face of increasingly overwhelming pressure was rooted in large part in their millennial faith that Christ would rescue them from their oppressors. It is true, no doubt, that nineteenth-century Mormons had a more robust premillennialist outlook than did Martin Luther King, as Pulsipher points out. But black civil rights workers at the grassroots level–those without doctorates from liberal northeastern seminaries–carried their movement out in prophetic, ecstatic biblical tones.”[1] Twentieth century southern black millennialism no doubt looked different than nineteenth-century Mormon millennialism. But both the Mormons’ resistance to federal anti-polygamy law and grassroots southern blacks’ resistance to Jim Crow arguably drew more deeply from the Hebrew prophets than from the American liberal tradition.

For those of us who know David, this article displays the quality of his mind and his character. It is expertly researched, with strong documentation. It is perceptive and measured in tone. It is fair-minded, fully acknowledging the twentieth-century critique of civil disobedience but gently suggesting that those critiques were shaped by a particular historical moment. And the article reminds us, in the grand tradition of the vaunted southern historian C. Vann Woodward, that the past is strewn with “forgotten alternatives” for our (re-)discovery and (re-)consideration.[2]

______

[1] David Chappell, A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 102.

[2] See C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002 [1955]), chap. 2.

By matt b.August 13, 2013

This is from John Fugal, A Review of Priesthood Correlation (Provo: BYU Press, 1968). There are any number of interesting points about correlation we can derive from this image, but most fundamental is this: though contemporary Mormons often speak of correlation as the formative era of the modern church, there is much that is foreign to present-day Mormons about material like this.

I want to make two related observations, though I’m sure there’s far more than that we can pick out.

1) Note the names of things. “Priesthood home teaching;” “Priesthood welfare;” “Priesthood missionary work.” Though correlation is often assumed to be somehow ‘secular’ – insofar as it is a form of bureaucratic reorganization and many Americans, steeped in Protestant notions of liberty, tend to find bureaucracy and the sacred a difficult reconciliation – there is intense linguistic effort here to interpret the institutional efforts of correlation as expressly religious. Indeed, according to its advocates and this chart, the purpose of correlation was to reinvigorate those aspects of church organization considered “sacred” – namely, the priesthood hierarchy. Notice how marginalized the auxiliaries are. Correlation was less, then, purely a secularizing force than a reorganization of ideas about the sacred and the secular in Mormon life, a narrowing and focusing of whence the sacred might come.

2) That process also may go a long way, I think, toward explaining the male paternalism of the correlated church. Another striking aspect of this image is its incorporation of the “home” into the structure of the church as another priesthood organization, like the Quorum of the Twelve or the ward. Centering correlation upon priesthood leadership necessarily exalts the status of men in the church, and the way this diagram reads the home is an excellent example.

By J StuartAugust 1, 2013

“Seventy years ago this Church was organized with six members. We commenced, so to speak, as an infant’. We advanced into boyhood, and still we undoubtedly made some mistakes, which did not generally arise from a design to make them, but from a lack of experience. Yet as we advanced the experience of the past materially assisted us to avoid such mistakes as we had made in our boyhood. But now we are pretty well along to manhood; we are seventy years of age, and one would imagine that after a man had lived through his infancy, through his boyhood, and on until he had arrived at the age of seventy years, he would be able, through his long experience, to do a great many things that seemed impossible and in fact were impossible for him to do in his boyhood state. While we congratulate ourselves in this direction, There are many things for us to do yet.[1]”

Continue Reading

By GuestJuly 22, 2013

[Another installment in this month’s series on “Mormonism and Politics,” this post is authored by Patrick Mason. Patrick, a friend of and mentor to many on the blog, is the Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University, and his works include The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormonism in the Post-Bellum South and (co-edited with David Pulsipher and Richard Bushman) War and Peace in Our Times: Mormon Perspectives. He is currently working on a biography of Ezra Taft Benson and a book on Mormon peace ethics. More recent family hobbies, supposedly related to peace ethics, include sneaking onto his former property with shovels and garbage bags to dig up grape vines and other shrubbery.]

The 1950s was a heady time for God in America. Postwar enthusiasm and the fear of the surge of international “godless Communism” helped spark a national revival of religion, both privately and publicly. Billy Graham emerged not only as the nation’s top revivalist but also as one of its biggest celebrities. “In God We Trust” replaced the more secularly inflected “E Pluribus Unum” as the nation’s motto, and “under God” got plugged into the Pledge of Allegiance.

Dwight Eisenhower’s appointment of LDS apostle Ezra Taft Benson as Secretary of Agriculture both reflected and enhanced this national religious renewal. Among students of Mormon history, Benson is well known for his association with the virulently anticommunist and arch-conservative John Birch Society. Benson never formally joined the JBS, but his son Reed became a national coordinator for the society and Ezra publicly stated on many occasions the he was “convinced that The John Birch Society was the most effective non-church organization in our fight against creeping socialism and Godless Communism.” (The best current treatment of this is in Greg Prince’s Dialogue article, here.)

Although his encounter with the John Birch Society in 1961 was significant for Benson, and in many ways helped define him and his public work for at least the entire decade of the 1960s, Benson did not need JBS founder Robert Welch to tell him that communism was evil or that America was God’s country. (We sometimes forget that virtually everyone in America, John F. Kennedy included, was an ardent anticommunist during the Cold War.) It’s more accurate to say that the John Birch Society was something like the salt that brought out the natural flavoring already inherent in Benson’s makeup.

Indeed, if we rewind nearly a decade before Benson ever heard of the society–several years before JBS even existed, in fact–we see an Ezra Taft Benson whose ardent patriotism is itself an article of faith. In an address given to the BYU student body on December 1, 1952, immediately after he had accepted his Cabinet appointment (but about six weeks before the Eisenhower administration would begin), Benson spoke on the relationship between the LDS Church and politics.[1]

When Eisenhower approached him about the job, Benson immediately offered several objections, including the fact that he had supported Ike’s opponent in the Republican primary. But one of Ike’s clinching arguments came when he told the apostle, “Surely you believe that the job to be done is spiritual. Surely you know that we have the great responsibility to restore confidence in the minds of our people in their own government “ that we’ve got to deal with spiritual matters.” Eisenhower thus framed government service as service to God, an argument that Benson would embrace whole-hog. This helped him assuage any doubts he may have had about securing a leave of absence from his full duties as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as he was simply temporarily exchanging one high-level calling from God for another.

In his address to the BYU students, Benson outlined some of his core principles. Central to his worldview was the inviolable and unmatched sanctity of the God-given principle of freedom of choice. For Benson, everything began with and came back to this one principle. It would come to define his political philosophy, his economic philosophy, and his religious philosophy. It also defined his patriotism. He would travel to dozens of nations during his time as Secretary, but his worldview had already been shaped by his mission to Europe in 1946, where he oversaw LDS relief and humanitarian efforts, and where he personally witnessed both the devastation of war and the slow retreat of freedom behind the lowering Iron Curtain.

To the BYU students, he proclaimed, “It’s a great blessing to live in America. It’s a great blessing to have the opportunity to enjoy the freedoms which are ours today. I have seen people, thousands of them, who have lost the freedom which is ours. . . . I’d rather be dead than lose my liberty. . . . When our system is criticized, just keep in mind the fruits of the system, the great blessings that have come to us because of our American way of life.”

Much of Benson’s love for and faith in the divine mission and millennial destiny of America came from the Book of Mormon, a text he returned to time and again throughout his life. He cited Book of Mormon passages about America being a “choice land” in every possible forum, from General Conference addresses to agricultural stump speeches to personal memos to President Eisenhower. Standing at the apex of the long Latter-day Saint tradition of sacralizing America, Benson often expressed his conviction that the Constitution of the United States was a “sacred document,” its words “akin to the revelations of God.” He was certain that “when the Lord comes, the Stars and Stripes will be floating on the breeze over this people.”[2]

The United States of America was not perfect, Benson conceded–the “creeping socialism” of the New Deal had eroded the sure foundations of the constitutional republic–but it was an essential part of God’s perfect plan for His children. But no Saint ever had to apologize for being a true-hearted American. God had indeed blessed America, and to honor the nation and its founding principles was to honor God.

Ezra Taft Benson was hardly the first nor the only Mormon to be an American exceptionalist or conservative constitutionalist. But perhaps more than any other single individual, he solidified a “special relationship” between twentieth-century Mormonism and the nation, a relationship that he alone, by virtue of both his high ecclesiastical and public office, was in a position to broker, and which no one championed more loudly, publicly, and sometimes controversially, than he did, for nearly half a century.

[1] Ezra Taft Benson, ?The L.D.S. Church and Politics,? Brigham Young University devotional address, Dec. 1, 1952; typescript in L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU. This address is one of many Benson speeches that have been given new life on the internet by LDS conservatives; for instance here.

[2] Ezra Taft Benson, The Constitution: A Heavenly Banner (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1986), 31, 33.

Newer Posts |

Older Posts

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

Recent Comments

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “Interesting, Jack. But just to reiterate, I think JS saw the SUPPRESSION of Platonic ideas as creating the loss of truth and not the addition.…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “Thanks for your insights--you've really got me thinking. I can't get away from the notion that the formation of the Great and Abominable church was an…”

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “In the intro to DC 76 in JS's 1838 history, JS said, "From sundry revelations which had been received, it was apparent that many important…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “"I’ve argued that God’s corporality isn’t that clear in the NT, so it seems to me that asserting that claims of God’s immateriality happened AFTER…”

Steve Fleming on Study and Faith, 5:: “The burden of proof is on the claim of there BEING Nephites. From a scholarly point of view, the burden of proof is on the…”

Eric on Study and Faith, 5:: “But that's not what I was saying about the nature of evidence of an unknown civilization. I am talking about linguistics, not ruins. …”