By CristineOctober 21, 2013

In August, I reviewed J.B. Haws’ recent article ?When Mormonism Mattered Less in Presidential Politics: George Romney?s 1968 Window of Possibilities?, published in the summer issue of the Journal of Mormon History. Haws, an Assistant Professor of Church History at BYU, graciously agreed to participate in a Q & A to answer some of my lingering questions and those submitted by members of the JI community. In the course of our conversation, we also discussed how the research he presented in his article is extended in his forthcoming (and highly-anticipated!) book, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (Oxford, December 2013), which promises to be an important and much-needed addition to our understanding of Mormonism in the contemporary period, as well as of public representations (and misrepresentations) of Mormonism across the last half of the 20th century.

JBH: I should say, by way of preface, that as I read through your questions, my reaction after every one was to think, ?Wow?great question.? But I?m going to resist typing that every time (but just know I?m still thinking that!). Thanks for these thoughtful and thought-provoking questions.

CHJ: Thank you, J. B.! We’re excited that you were willing to offer us some answers. So?let’s get to it!

Continue Reading

By Edje JeterOctober 20, 2013

Second only to polygamy, Mormons in the second half of the nineteenth century were known for violence. Paramilitary groups of ?Danites? or ?Avenging Angels? allegedly surveilled, threatened, and/or killed as directed by Church leaders. In three instances that I know of, non-Mormons portrayed members of these groups as using robes, hoods, and masks like those of the Ku Klux Klan. The purpose of this post is to put all three instances on the same page at the same time.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 27, 2013

Alan Morrell, a curator at the Church History Museum, contributes this installment in the JI’s material culture month. Alan is completing a doctorate in American History at the University of Utah, and he has degrees from BYU and Villanova.

I have an iPhone because I once missed an appointment. I was so engulfed in my research, I forgot about a meeting and didn’t realize it until it was already over. My wife teases me about being absent-minded, but she wasn’t amused when I told her what had happened. After years of marriage to a poor grad student, she was thrilled that I had a paying job. She worried that I’d screw it up so she went out and bought me something that could keep me on track. Now, the time and my schedule are always available, with reminders of upcoming appointments.

In our hyper-connected modern world, we quickly learn to become time conscious. David S. Landes, author of Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World considered the mechanical clock to be “one of the great inventions in the history of mankind: not in a class with fire and the wheel, but comparable to movable type in its revolutionary implications for cultural values, technological change, social and political organization, and personality.”[1]

Historian Alexis McCrossen examined the records of watch repairmen in 19th-century western Massachusetts and observed that “Americans had been living with watches and clocks for decades without fully tapping into the potential they provided for coordination and maximization of time.”[2] This changed in the 1820s when the volume of pocket watches in the United States increased drastically. By the 1840s, the price of a clock or watch had dropped to the point that even a person of modest income could afford one.

John Taylor. Courtesy Wikimedia

This was the world of John Taylor. Born on November 1, 1808 in Milnthorpe, Westmorland, England, he moved to Toronto, Canada, in 1832. Six years later, he was a Mormon apostle. I do not know when John Taylor started carrying a watch. The multiple appointments of a Latter-day Saint leader would have certainly required that Taylor be conscious of the time. The narrative history that Joseph Smith started in 1838 demonstrates that time consciousness was an essential part of the Mormon community. Recorders noted the times of events such as the departure of the “Maid of Iowa” at 10 A.M. on May 1, meetings of Church leaders from 2 to 6 and again from 8 to 10 P.M. the next day, or a court martial at 9 A.M. on May 4.[3]

It is not surprising, then, that on the evening of June 27, 1844, John Taylor was wearing his watch as he sat with Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Willard Richards. The previous days had been busy as he met with the governor, lawyers, and leading citizens in an effort to free the Smith brothers. Readers know the story of the martyrdom. Within minutes, Joseph and Hyrum Smith were dead and John Taylor was severely injured. Taylor described getting shot, “As I reached the window, and was on the point of leaping out, I was struck by a ball from the door about midway of my thigh. . . . I fell upon the window-sill, and cried out, ‘I am shot!’ Not possessing any power to move, I felt myself falling outside of the window, but immediately I fell inside, from some, at that time, unknown cause”[4]. He was badly wounded. Four bullets had ripped through his body, one tearing away a portion of his hip the size of his hand. Willard Richards who escaped the barrage without injury dragged Taylor into a cell, covered him with a mattress in an effort to hide him, and said he hoped Taylor would survive as he expected to be killed within a few moments. The mob, perhaps fearing that the Mormons were coming, fled. Both Taylor and Richards were spared.

John Taylor’s Watch. Courtesy PBS

Willard Richards had John Taylor moved to Hamilton’s tavern and then went about the business of preparing for the removal of Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s bodies. When Richards left for Nauvoo, John Taylor asked him to take his watch and purse with him, as he feared they would be stolen. Several days later, Taylor was at his home in Nauvoo still convalescing when he was once again reunited with his watch. At this moment, the watch was transformed from a mere timepiece to a holy relic. His family discovered that the watch had been “struck with a ball” and examination of his vest revealed a cut in the vest pocket that had contained his watch. He later explained, “I was indeed falling out [of the window at Carthage Jail], when some villain aimed at my heart. The ball struck my watch, and forced me back; if I had fallen out I should assuredly have been killed, if not by the fall, by those around, and this ball, intended to dispatch me, was turned by an overruling Providence into a messenger of mercy, and saved my life.” He concluded, “I felt that the Lord had preserved me by a special act of mercy; that my time had not yet come, and that I had still a work to perform upon the earth.”[5]

The story of John Taylor’s miraculous preservation spread quickly. Within a few weeks, several accounts mentioned that Taylor’s watch had been hit by a ball.[6] The watch become an integral part of the telling of the martyrdom; the story spread wide and far. The relic remained in the family until 1934 when John Taylor’s grandson, Alonzo Eugene Hyde, Jr., gave it to LDS President Heber J. Grant, who forwarded it to the museum at the Bureau of Information, a precursor of the Church History Museum.[7] Since 1990, the John Taylor watch has been on public display at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, a highlight for visitors of the museum’s “A Covenant Restored” exhibit.

By the latter part of the 90s, several individuals began to research and write about their questions surrounding the long-accepted story of the John Taylor watch. They could not believe that a musket ball would do so little damage to a watch. In Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, Historian Glen Leonard cited the unpublished research of Neal and Gayle Ord when he wrote that after John Taylor was first shot in the leg, “He collapsed on the wide sill, denting the back of his vest pocket watch. The force shattered the glass cover of the timepiece against his ribs and pushed the internal gear pins against the enamel face, popping out a small segment later mistakenly identified as a bullet hole.”[8] Joseph L. and David W. Lyon’s 2008 BYU Studies article “Physical Evidence at Carthage Jail and What it Reveals about the Assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith” is probably the most exhaustive published scholarship arguing this position.[9] A couple years later, Joseph Lyon’s scholarship received popular attention after his presentation at BYU Education Week.[10] Kenneth W. Godfrey’s interview for the KJZZ Joseph Smith Papers television series furthered this narrative for a popular audience.[11]

A search of sources, both popular and scholarly, online and in print, shows that both stories are alive and well today. This begs several questions. Has the window sill explanation become the new master narrative for scholars? Has this narrative moved out of scholarly circles into the Mormon mainstream? Does the window sill remove the miraculous from the story? Do some individuals use this as another example of scholars just trying to destroy faith? Is there any evidence of deceit by those who originated or propagated the original story? Regardless of the answers to these questions, we should be grateful that John Taylor believed the watch saved his life. It may be the only reason it is still around. What good is a watch that doesn’t keep time?

______

[1] David S. Landes, Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 1983), p. 6.

[2] Alexis McCrossen, “The ‘Very Delicate Construction’ of Pocket Watches and Time Consciousness in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” Winterthur Portfolio Vol. 44, No. 1 (Spring 2010)

[3] Historian’s Office history of the Church 1839-1882. http://eadview.lds.org/findingaid/CR%20100%20102, Book F1

[4] “The Martyrdom of Joseph Smith” by President John Taylor (http://archive.org/stream/cityofsaintsacro00burt#page/517/mode/2up), Appendix III.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Jenetta Richards letter to her family, 8 July 1844, in Our Pioneer Heritage, vol. 3, p. 130; Times and Seasons 15 July 1844; Nauvoo Neighbor 24 July 1844; and Times and Seasons 1 August 1844

[7] Deseret News, 8 November 1934

[8] Glen M. Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, Deseret Book, 2002, pp. 397-98.

[9] Joseph L. Lyon and David W. Lyon, “Physical Evidence at Carthage Jail and What It Reveals about the Assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” BYU Studies 47:4. https://byustudies.byu.edu/showTitle.aspx?title=7980

[10] “Education Week: Separating Facts from Fiction about the Prophet’s Death,” Deseret News, Sept. 7, 2010, http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705385933/Education-Week-Separating-facts-from-fiction-about-the-Prophets-death.html?pg=all

[11] “John Taylor’s Watch ‘The Real Story” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOlH26SE55k

By GuestSeptember 24, 2013

Almost exactly one year ago, the University of North Carolina Press published Edward Blum and Paul Harvey’s The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, a sweeping and provocative analysis of the ways in which Americans from various walks of life over the last four hundred (!) years have imagined Jesus. Among the many contributions the book makes, and of particular interest to JI readers, is the authors’ situating Mormons as important players in the larger story of race and religion they narrate so masterfully. In fact, one paragraph in particular has garnered more attention than nearly any other part of the book—a brief discussion in chapter 9 of the large, white marble Christus statue instantly recognizable to Mormons the world over. In the latest issue of the Journal of Mormon History, Noel Carmack authored a 21 page review of The Color of Christ, focusing on their treatment of Mormonism and paying particular attention to their discussion of the Christus. Professors Blum and Harvey generously accepted our invitation to respond here, as part of both our ongoing Responses series and as an appropriate contribution to our look at Mormon material culture this month.

Continue Reading

By GuestSeptember 13, 2013

Michael J. Altman received his Ph.D. in American Religious Cultures from Emory University and is an Instructor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Alabama. Mike’s areas of interest are American religious history, theory and method in the study of religion, the history of comparative religion, and Asian religions in American culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript analyzing representations of Hinduism in nineteenth century America. This post originally appeared at Mike’s personal blog. He graciously allowed the Juvenile Instructor to repost it in its entirety.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, a sports podcast that deconstructs sports media and culture with a wry wit that deflates American sports of all its self-seriousness. If sports talk radio is Duck Dynasty, Hang Up is 30 Rock.

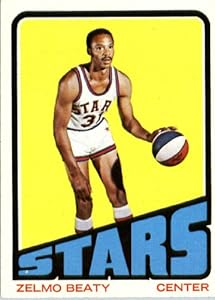

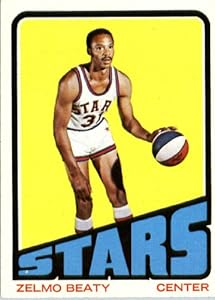

Every week host Josh Levin signs off with the phrase “remember Zelmo Beaty.” Beaty, a basketball star in the 60s and 70s passed away recently and this past week Hang Up and Listen reminded us why we should indeed remember him. Stefan Fatsis’ obituary of Beaty opened by staking out Beaty’s importance as a pioneer for black players in professional basketball. But what caught this religious historian’s attention was the confluence of race and religion that surrounded Beaty’s move to Salt Lake City to play for the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association in 1970.

Continue Reading

By ChristopherSeptember 4, 2013

As a sort of follow-up to my post a couple of weeks ago on early Mormonism on the Jersey Shore and as my own contribution to the blog’s emphasis on material culture this month, I thought I’d offer some brief thoughts on Mormon images of Christ and their appropriation and use by non-Mormons.

Earlier this summer, a family member handed me a handful of pamphlets she’d picked up during a recent trip to the Jersey Shore. Knowing of my own interests in Methodist history, she thought I’d appreciate the literature she’d picked up at the Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association in Ocean Grove, New Jersey. Methodism has a long and rich history in New Jersey—Asbury Park, a seaside community made famous by Bruce Springsteen, was named after the father of American Methodism, Francis Asbury, and the town of Ocean Grove traces its own roots to the efforts of two Methodist ministers in the mid-19th century to establish a permanent camp meeting site to host summer retreats and worship services. While I found the content of the pamphlets interesting, I was struck most by the image adorning the tri-fold pamphlet advertising a series of lectures entitled “Our God Present During Difficulty.”

Continue Reading

By ChristopherAugust 26, 2013

The original Heisenberg?

Over at the blog for The Appendix: A new journal of narrative and experimental history, Benjamin Breen has written a fascinating post on historical discoveries of illicit drugs. Capitalizing on the success of Breaking Bad‘s final season (a show centered around the dealings of a cancer-diagnosed high school chemistry teacher-turned-meth cook), Breen notes that while “the invention of Breaking Bad‘s blue meth has become the stuff of television legend” very few people “know the true origin stories of illicit drugs.”

After briefly covering “the first academic paper on cannabis” (penned in 1689 by British scientist Robert Hooke, who noted that ?there is no Cause of Fear, tho’ possibly there may be of Laughter.”), Freud’s 1884 publication extolling the virtues of cocaine, and “Albert Hoffmann?s accidental discovery of acid,” Breen turns his attention to “the strange fact that methamphetamine was actually invented in 1890s Japan.” In 1893, Nagayoshi Nagai successfully synthesized meth by “isolat[ing] the stimulant ephedrine from Ephedra sinica, a plant long used in Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine.” For those interested in the whole story, I recommend clicking over and reading the entire post—it really is quite fascinating. But one throwaway line caught my attention and will almost certainly interest readers here. Describing ephedrine, Breen notes that it “is a mild stimulant, notable nowadays as an ingredient in shady weight-loss supplements and as one of the few drugs permitted to Mormons.”

Continue Reading

By CristineAugust 19, 2013

Mitt Romney?s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns came to seem, in the media frenzy of the last few years, like bookends to America?s much-touted Mormon moment. But Americans? fascination with the Latter-day Saints did not begin or end with Mitt Romney. This is not the first period in American history when non-Mormon Americans have, to some extent, embraced their LDS neighbors. In fact, Mitt Romney isn?t even the first Republican Romney whose religious affiliation has colored his national political image. His father George, the successful head of the American Motor Company in the 1950s and popular governor of Michigan in the 1960s, was a prominent candidate for the 1968 Republican nomination for President. Also like Mitt, George owed at least some measure of his political success to a period of increased interest in and positive feeling towards the Mormons. As J.B. Haws, Assistant Professor of Church History at BYU, shows in his article in the most recent issue of the Journal of Mormon History, George Romney?s candidacy was not seen as tainted by a ?Mormon problem,? as were his son?s campaigns a half-century later. [1] In the United States in the 1960s, the Romneys? Mormonism simply ?mattered less? than it does in the 21st century. And if it mattered at all, Haws argues, it did so by lending George Romney the air of ?benign wholesomeness? that characterized public perceptions of the Latter-day Saints in this period (99).

Haws? current article is based on the research for his forthcoming book The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (OUP, November 2013), and essentially lays the groundwork for that longer study, in which he traces public perceptions of Mormonism in the American media across the last half-century. In the 1960s, he argues, George Romney ran for the Republican nomination for the presidency and faced remarkably few challenges to his religion?or at least what look like remarkably few challenges to those of us who lived through the most recent Mormon moment. By comparing political polling data from both Romneys? campaigns and examining news coverage of the elder Romney?s presidential aspirations and editorial commentary on his campaign and on the larger question of the role a candidate?s religion should play in voters? assessment of his fitness for office, Haws convincingly demonstrates that Americans were less concerned in the 1960s?or at least said they were less concerned?by the possibility of having a Mormon in the White House than were their early 21st-century counterparts. While George Romney?s religion was occasionally challenged?primarily, Haws claims, regarding the Church?s policies on race (remember, George Romney was running for the presidency in the midst of the Civil Rights movements, and a decade before the Church lifted its ban on blacks in the priesthood)?according to Haws it was not Romney?s religion but his moderate politics and his ill-advised declaration in 1967 that he had been ?brainwashed? into supporting the Vietnam war that sunk him with American voters. In short, Haws argues that political views, not religious beliefs, were the elder Romney?s greatest obstacles.

Continue Reading

By Mees TielensAugust 8, 2013

As part of this month’s series on 20th century Mormonism, I’d like to take a brief glance at BYU and the 1984 National Championship. For those unfamiliar with 1980s sports history, BYU won the national championship for the very first time in 1984. As a 2009 article puts it, “I can’t think of a more unlikely national champion … an unranked (preseason) team from a non-power conference.” I refer you to the article for an analysis of games played; today, I’m going to give you a few media perspectives on the win.

Continue Reading

By Tona HAugust 7, 2013

In 2009 our stake organized its first trek for youth conference and put it into the regular rotation for youth conference planning. So 4 years later, we repeated the event this summer with roughly the same itinerary and logistics and presumably will keep it going in future years as well. Now, you may know that I live in New England, not in the Wasatch front region or along anything remotely resembling a traditional handcart route. Treks outside the historical landscape of the handcart companies have become commonplace: unusual enough to generate local news coverage, but frequent enough that a whole subculture has sprung up to support and celebrate it. With some similarities to Civil War reenactment in its emphasis on costuming, role play and historical storytelling, youth trek evokes and romanticizes selected aspects of the Mormon past to cement LDS identity and build youth testimony and unity. It is a unique (and, I?m arguing, actually very recent) form of LDS public history.

I?ve now attended and had a hand in planning both of the treks our stake conducted, so I?m of two minds about the whole experience. A double-consciousness, if you will.

Continue Reading

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

One of my favorite weekly podcasts is Slate’s

Recent Comments

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “Interesting, Jack. But just to reiterate, I think JS saw the SUPPRESSION of Platonic ideas as creating the loss of truth and not the addition.…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “Thanks for your insights--you've really got me thinking. I can't get away from the notion that the formation of the Great and Abominable church was an…”

Steve Fleming on BH Roberts on Plato: “In the intro to DC 76 in JS's 1838 history, JS said, "From sundry revelations which had been received, it was apparent that many important…”

Jack on BH Roberts on Plato: “"I’ve argued that God’s corporality isn’t that clear in the NT, so it seems to me that asserting that claims of God’s immateriality happened AFTER…”

Steve Fleming on Study and Faith, 5:: “The burden of proof is on the claim of there BEING Nephites. From a scholarly point of view, the burden of proof is on the…”

Eric on Study and Faith, 5:: “But that's not what I was saying about the nature of evidence of an unknown civilization. I am talking about linguistics, not ruins. …”